It was the story people couldn't stop sharing. Nina Davuluri's victory at the 2014 Miss America contest set off an explosion of racist tweets, which news sites quickly bundled into stories that immediately seemed everywhere online. One group's rage sparked another's: On Facebook and Twitter, a cacophony of irate individuals expressed outrage at other people's anger. A single Buzzfeed story about the racist posts, "A Lot Of People Are Very Upset That An Indian-American Woman Won The Miss America Pageant," was shared by more than 62,000 people and has been viewed over 5.3 million times.

The racist tweets, as well as the outrage they produced online, underscore an important but often ignored truth about the kind of conversation that social media encourages: The wisdom of crowds is no match for the rage of crowds.

Madison Avenue taught the world that "sex sells." But that motto needs an update in the social media age, where information travels in new ways and is carried along by different people. Online, rage rules. I hate, therefore I "like." (And since everyone wants a "like," people aim to provoke.)

"Negative comments are much more memorable and much more noticed," observed Stanford University professor of communication Clifford Nass in an interview earlier this year. "In a world where you're trying to get noticed, going negative is the way to go."

As a growing body of research shows, subtlety isn't what succeeds on social networks. Anger-inducing, emotionally-charged content spreads best, and the success of those posts may in turn be shaping the way we think and communicate with one another -- lending an almost feverish pitch to our interactions online. Although social media sites claim they're about kumbaya social connection, their design actually makes them extremely well-suited to arousing our emotions.

Many have argued precisely the opposite, saying that Facebook, Twitter and even email are some of the most effective mechanisms ever devised for spreading happy stories. And there is some research to support this: We're incentivized to share helpful, heartwarming and hilarious things, since these make us look good to our friends. The language of Facebook and Twitter, with "likes" and "favorites," also gives happy stuff a boost. "[N]euroscientists and psychologists have found that good news can spread faster and farther than disasters and sob stories," wrote The New York Times' John Tierney earlier this year. The title of his piece declared, "Good News Beats Bad on Social Networks."

That sounds nice, only it's not entirely true. And that's not necessarily a bad thing.

Research published last week by a team at China's Beihang University concluded that anger was more contagious than other emotions, spreading faster and more widely online than sadness, disgust and even joy. The scholars examined 70 million posts from China's Weibo, a Twitter-like service used by over 500 million people, and tracked how people who interacted frequently with one another influenced the emotional tone of each other's posts. Did certain sentiments spread more quickly than others? Would an angry message posted by one person be more likely to prompt another angry post, than, say, a depressing or happy one? Absolutely, they concluded.

"We find the correlation of anger among users is significantly higher than that of joy, which indicates that angry emotion could spread more quickly and broadly in the network," the researchers wrote. The title of their paper says it all: "Anger Is More Influential Than Joy."

A 2011 study that examined the diffusion of sentiment across Twitter reached a similar conclusion, albeit with an exception. The researchers found that in the domain of news, bad news is viral news, or "negative news is more retweeted than positive news." But non-newsy tweets, such as social updates, were shared more when they were positive. The authors advised people seeking out more followers to "sweet talk your friends or serve bad news to the public."

Those who maintain that cheerful trumps dreadful online frequently cite the research of Wharton School professor Jonah Berger, the author of "Contagion: Why Things Catch On." In one study, Berger and his co-author Katherine Milkman analyzed nearly 7,000 stories that made it to The New York Times' most-emailed list to figure out if they could decode a pattern to the articles' popularity. They found uplifting stories (i.e. "Wide-Eyed New Arrivals Falling in Love with the City") were more viral than depressing ones. But "highly arousing content," like articles that induced anxiety or anger, did best of all.

"Online content that evoked high-arousal emotions was more viral, regardless of whether those emotions were of a positive (i.e. awe) or negative (i.e. anger or anxiety) nature," the researchers noted -- a conclusion echoed by a slew of other studies. When emotionally charged content gets readers agitated, their instinct is to hit "share."

These findings have major implications for our experience online, far beyond how to win more followers. They suggest that social media can actually reward-- through its currency of shares, retweets and "likes" -- outbursts of rage and anything that make us agitated. Hype wins, nuance loses.

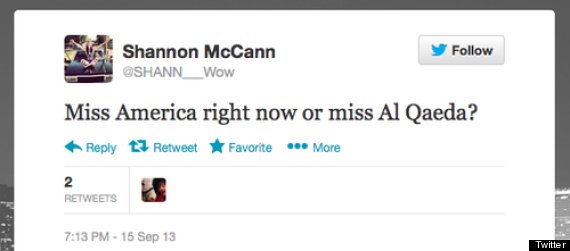

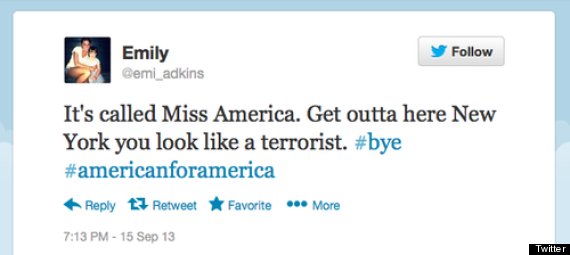

Tweets sent following Davuluri's victory, some of which have seen been deleted. (via PublicShaming.tumblr.com.

Tweets sent following Davuluri's victory, some of which have seen been deleted. (via PublicShaming.tumblr.com.

The problem with the viral nature of extreme emotions is that we both ingest that content and emulate it. If that's what we share then that's what we'll see, which in turn will shape how we act. It's not a leap to suggest heated emotions breed more heated emotions online, or rage more rage. A study by Facebook's data science team found that if people used negative words, such as "petty" or "lame," in their status updates, their friends became more likely to include negative words in their own posts. The bump in usage persisted even three days after the initial post, and the effect also applied to positive terms.

Just as we act differently at frat houses and family reunions, we adjust our behavior online according to what we see around us. Instagram got people to share gorgeous photographs by initially seeding the app with a small community of artists and designers. If we reward people posting nasty things with our attention -- and we do -- that becomes the acceptable standard.

Pundits have raised concerns that the Internet's hyper-personalization might lead to a "filter bubble," where people see only content that reinforces their existing interests and views. This, they argue, could lead to more polarized political views and stronger biases, while decreasing curiosity and creativity. But we should be just as concerned about the tone of what we see as its topic. Pandering to emotion might get us to read and share something, but it won't make us more thoughtful people. And the research suggests hysteria may be winning the web.

But the success of anger online isn't always a problem, either. In fact, the viral nature of rage has proven a powerful force that can bring attention to issues -- especially in countries lacking a free press. The Beihang University study of Chinese social media found two prime events were most likely to set off angry posts, both of them political: diplomatic disputes with other countries, and domestic ills, such as corruption, bribery and food safety scandals. Weibo, they wrote, "is a convenient and ubiquitous channel for Chinese to share their concern about the continuous social problems and diplomatic issues."

Even the disparaging tweets about the new Miss America could have some function, beyond their unfortunate intention to just spew hate: They force people to acknowledge persistent racism and misunderstanding. If we see the problem, and the anger, perhaps it's easier to address it.

This story appears in Issue 69 of our weekly iPad magazine, Huffington, available Friday, Oct. 4 in the iTunes App store.