Suppose you are sending your 12-year-old daughter off to a summer camp two states away and she is flying on a plane by herself for the first time. Would you put her on that plane if you knew that it had less than a 10 percent chance of landing safely at its destination?

Why do we accept these odds when it comes to animal experimentation? If you were volunteering for a clinical trial, there is more than 90 percent chance that the drug that tested safe and effective in animals will be ineffective or unsafe in you.

In the previous blogs in my series on animal experimentation, we reviewed the three main reasons why animal experimentation doesn't work. Unlike failures in many other scientific areas, the failure of animal experimentation has a high cost -- and harms us in three crucial ways:

1. Misleading Safety Tests in Animals Directly Hurt Humans.

In March, 2006, six human volunteers were injected with TGN 1412, an experimental therapy created by TeGenero. As described by Slate:

Within minutes, the human test subjects were writhing on the floor in agony. The compound was designed to dampen the immune response, but it had supercharged theirs, unleashing a cascade of chemicals that sent all six to the hospital. Several of the men suffered permanent organ damage, and one man's head swelled up so horribly that British tabloids refer to the case as the 'elephant man trial'.

TGN 1412 was tested in mice, rabbits, rats and monkeys with no ill effects. In addition, cynomolgus monkeys were used because they best replicated the human mechanisms specifically targeted by TGN 1412 (1). Thus, not only were several different species used, those deemed most relevant to humans were used. Monkeys also underwent repeat-dose toxicity studies and in fact were given 500× the dose given to the human volunteers for not less than four consecutive weeks. Still, none of the monkeys manifested the ill effects that humans showed within minutes of receiving a miniscule amount of the test drug.

TGN 1412 exemplifies how animal experiments are notably unreliable for determining if a chemical or drug will be safe in humans. Here are some other examples where animal experiments hurt people:

- In 2003, Élan Pharmaceuticals had to stop trials of an Alzheimer's vaccine that had cured the disease in "Alzheimer's mice," after the substance caused brain inflammation in humans (2).

Thus, far from protecting us, animal experimentation puts us at greater risk of harm. Additionally, the indirect harms as a result of misleading tests can be substantial.

2. Misleading Animal Experiments May Cause Us to Throw Away Cures

It is hard to quantify how many missed opportunities there may have been because of misleading animal experiments. However, there are plenty of examples that demonstrate how lucky we are that researchers did not believe the animal tests. For example:

- An editorial in Nature Reviews Drug Discovery describes how tamoxifen, one of our most effective drugs against certain types of breast cancer, would have been abandoned because it causes liver tumors in rats, a problem that does not carry over to humans.

As Dr. John Pippin argues:

Gleevec is a success of rational drug design and human-based drug testing -- a life-prolonging success that would have been lost if the results of animal research had prevailed.

- Experiments on animals delayed the acceptance of cyclosporine, a drug widely and successfully used to treat autoimmune disorders and prevent organ transplant rejection (5).

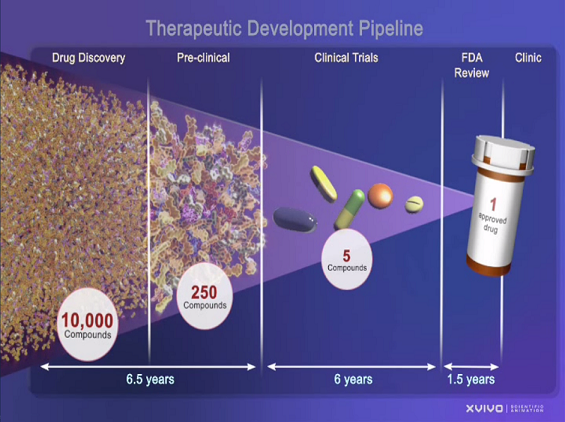

Of every five to 10,000 potential drugs tested in the lab, only about five pass on to clinical trials. Many don't pass the animal tests because of species-specific results. Yet many of these agents would likely have worked spectacularly and been safe in humans.

One can't help but wonder how many people would have been saved if human-based tests that would better predict harmful effects and drug efficacy were used rather than animal experiments?

And so we come to the last major harm.

3. Time and Money Wasted on Animal Experiments Could Have Been Directed into More Fruitful Human-Based Tests.

An invalid disease model can lead the industry in the wrong direction, wasting time and significant investment. On average, it costs a company more than $1 billion to get one new drug to the market. NIH alone spends almost half of its funding -- up to 14.5 billion of our tax dollars yearly -- on animal experiments.

Repeatedly, researchers have been lured down the wrong line of investigation because of information gleaned from animal experiments that later proved to be inaccurate, irrelevant or contrary to human biology. It's taken over 25 years of failed HIV vaccine clinical trials for researchers to seriously question the usefulness of non-human primate HIV experiments, and over 30 years before we realized that the rodent model of diabetes is wrong.

We can be pretty confident that the victims of the TGN 1412 disaster will never risk their lives based on animal experiments again. In fact, a human-based in vitro test would have predicted the harmful effects and protected those men (7).

How many more people need to suffer and die before we realize that, if we really want to help ourselves, we need to cut out the animal experiments and focus on more effective human-based tests?

Stay tuned for the next blog in the series!

Want to know more? Check out my website and join me on Facebook.

Footnotes

- Akhtar (2012) Animals and public health. Why treating animals better is critical to human welfare. Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 147-148.