When I was growing up in Chicago during the late 1950s to mid-1960s, we were told that the city might be destroyed by nuclear war at any moment, and the only advance warning would be a siren. It would not help to flee, since the streets would be clogged with hysterical motorists. Your only chance would be to head toward the nearest basement, place your head against the wall and wait. We practiced that in "air-raid drills" at school. Quite a few people were building air-raid shelters, and post-apocalyptic dramas on television often added to the terror. Not infrequently, I would be walking along the street, and hear a noise that I thought was the "siren," at which I would be too frightened to even run.

The possibility of a nuclear war no longer inspires such terror, though it is still with us. Is that because the danger has receded? Is it more because we have simply gotten used to, or resigned to, living with the prospect of annihilation? Have we ceased to feel the dread, or have we grown more skilled at pushing it from our minds? To an extent it has been replaced by, or merged with, other apocalyptic fears such as a Fascist takeover, descent in chaos, economic collapse or, most especially, environmental destruction.

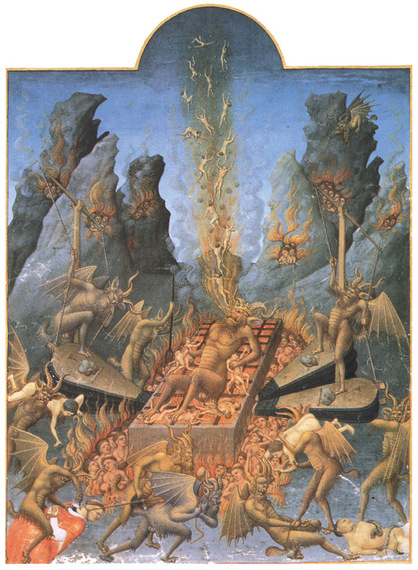

Apocalyptic fears may be found in any historical era, but they wax and wane. In Western culture, they reached a high point in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance, and were often expressed in graphic depictions of the end of the world and of sinners in Hell. Demons were shown, as in Dante's Inferno, inflicting all manner of tortures on the damned, but most of the emphasis is usually on bodily consumption. They are, in other words, herding, cooking, devouring and excreting men and women. Nevertheless, invocations of Hell were not unequivocally terrifying, and possibly as much a matter of style as religion.

The demons in Hell are often depicted with a touch of humor, and it may at times be that the grotesque exaggeration in paintings of them even involve an element of satire. When they open their huge mouths, you cannot always tell a snarl from a grin. Often, the monsters seem less evil than simply bestial, like creatures in the wild following their instincts. For most viewers, the terror, genuine though it might be, was mixed with fascination. The depictions of Hell, in other words, were entertainment, not entirely unlike horror movies today. The late medieval preoccupation with demons resembles our contemporary obsession with Nazis, which are often caricatured to a point where they no longer seem to be human beings.

The apocalyptic imagery of that era faded very gradually. Part of the reason may be the greater security of Europeans and Americans on a day-to-day basis. Life expectancy in the Western world nearly doubled in the 18th and 19th centuries, and then almost doubled once more in the 20th. Even in the poorest countries today, human life expectancy is now far longer than it was anywhere in pre-modern times. But, as the two World Wars so forcefully reminded us, the chances of a cataclysmic disaster have greatly increased, so we have merely traded in one type of insecurity for another. Perhaps the representations of end times simply lost their effectiveness through excessive use.

Apocalyptic imagery has again lost its attraction through repetition over the past several decades. The use of a post-apocalyptic setting has now become fairly well-established in fiction. It is usually detached from any very immediate political or social context. The devastation that precedes the main narrative in Cormac McCarthy's The Road or Suzanne Collins' Hunger Games is not a warning, merely the background of a story.

This was apparent to me in reading Elizabeth Kolbert's recent book The Sixth Extinction. The crisis she describes is certainly one of apocalyptic dimensions. By around the middle of this century, scientists estimate that about a third of amphibians, a quarter of all mammals, a fifth of all reptiles and a sixth of all birds will be extinct. This, in turn, will have profound, but unpredictable ecological consequences, which could ultimately jeopardize human survival. Kolbert reports on the crisis though a combination of history, science and personal experience, yet the book is notable for its lack of preaching.

While she often mentions the ability of humankind to save a few selected species, she speaks of the sixth great extinction almost as though it had already taken place. This is quite a contrast with, for example, Jonathan Schell's book The Fate of the Earth, published back in 1982, which horrified the public by describing in very specific detail what would happen if a nuclear bomb were detonated in Manhattan.

However severe the crisis, apocalyptic imagery remains only one way to speak of it, and it is by no means necessarily the most productive. Its advantage is that it can at times shock people into action. The disadvantage is that it may instead lead to panic, despair or denial. In addition, people at times start to enjoy apocalyptic imagery a little too much.

Post-apocalyptic writing, by contrast, risks not doing full justice to the reality of the dangers that we face. But perhaps it confronts them with greater humility, by acknowledging the limits to our understanding, responsibility and control.

André Jacques Victor Orsel, "The Devil Tempting a Young Woman," 1832. The trumpet of the demon may signal the end of time, but the young woman does not appear overly concerned.

Limbourg Brothers, "Tundal's Hell," from Trés Riches Heures, c. 1416. These demons may be tormenting sinners, but they appear almost more playful than diabolic.

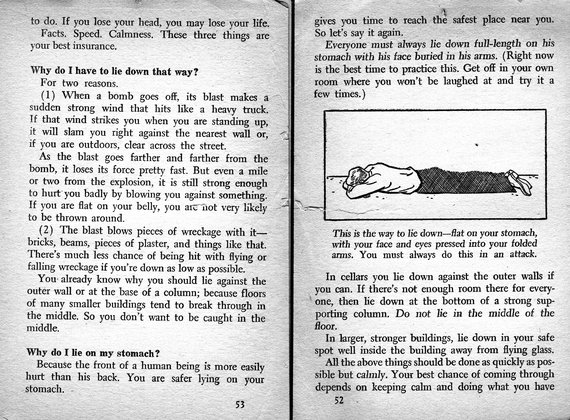

From How to Survive an Atomic Bomb by Richard Gerstell, 1950. This book was avowedly written to reassure people, but it further terrified them instead.