Are Ads Now Our International Language?

By Paula DiPerna

At last, those nasty television screens in New York City taxis are going to be eliminated, according to news from the Taxi and Limousine Commission. Drivers hated the screens because passengers kept complaining. The ads started scrolling as soon as the meter started running, and shutting down the screen had become nearly impossible since the "shut down" tabs never responded. In a cab, we were prisoners of ads, as were the taxi companies too, who hoped that the ads would bring them revenue. But, the ads were a desperate funding attempt, the protest was overwhelming and so, goodbye.

Ads, as we know, are the new conveyance of content and culture. Without them, the business model for the internet falls apart. But with them, time is drained off and downloading is slow. Software to block ads is increasingly popular. But if ads go away, what will go with them?

Perhaps a part of us? For ads maybe are increasingly our mirror. So suggests writer and literary critic, Maria Nadotti, in her new and provocative book "Necrologhi: Pamphlet on the Art of Consumption." Published in October by Il Saggiotore, using words and sometimes images alone, the book could well become a global touchstone. The title itself is a pun, combining the plural of necrology and the Italian plural of "logo"-- a statement to question whether the timelessness ads try to convey is, actually, time frozen to worship a dark side. As geographical boundaries blur, blurring cultures too, ads have emerged in an odd way as a form of global language and inscription of political trends. A cultural language as well.

To Nadotti, today's ads more than ever dip deep into the culture, including ancient mythologies that tap conscious and unconscious. Nadotti in some chapters focuses on ads of bodies--all forms of bodies. She says, "We see in ads bodies of all types, in all kinds of positions and poses, and they remind me of mythological monsters and characters, especially Narcissus. We see this in the message of the child who never will grow up, whose image freezes them in childhood. Or we see ads that try to say that people will never grow old, they stay as they are, and they will fight against getting older."

Or, as in myth, Nadotti highlights how ads are now tagging along on the purity of nature itself, nature now playing a major role in ads--land, nature, crops, water. Says Nadotti, "even selling something as simple as coffee, we today sell environmental consciousness. Today we have 'goodness is a product', as implied in ads insinuating that the choice of a certain brand of coffee or jeans will help save the world, or oneself."

It's true that just after I spoke with Nadotti, I spotted a billboard ad on a bus, the size of an elephant (meaning expensive), for bottled water in New York City, where normal tap water is the cleanest and best in the world. The ad linked the buzz of the city with pushing the product. On top of the ad was praise for New York as "Home of the Hustle." Then, rippling across the ad and clear drops of transparent irresistible water, the pitch: "Hydrate the Hustle." But, other than marathon runners, in fact, no normally healthy person needs to hydrate to the point of carrying a bottle of water all day, some even sipping from a nipple as they walk, like a thirsty infant. But the ad world has put across the idea that bottled water is an essential, raining plastic litter everywhere and turning the idea of water from a basic necessity that should be free to all to a luxury item as rare as perfume. So much for environmental consciousness.

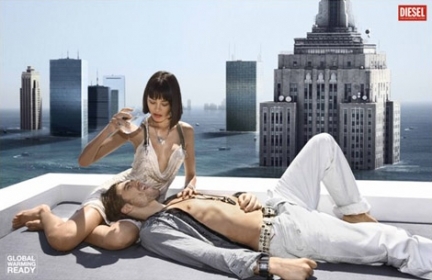

But at the heart of Nadotti's critique is the astute observation that ads today are drawing on violence for inspiration and, thus, tending to turn violence into a hum-drum affair, a logoi-ization, so to speak, of war and cruelty. Have we become so inured to these events that we do not mind them being used to sell us products? So wonders Nadotti. She notes that she has even seen ads that place bodies in the same grotesque poses as victims who were killed in unforgettably awful events, such as when the Russian army stormed a Moscow theater where hundreds of hostages were being held and many were killed in the battle, their bodies filmed by media worldwide.

Nadotti describes ads where "high heeled models walk among war ruins and androgynous boys lie idly, half paramour, half Passion of the Christ." She wonders "why am I supposed to be attracted to products that use these types of images. You have the strange feeling of having already seen what you have seen. Even those horrible photos from Abu Graib prison--each one has its equivalent in advertising."

Nadotti loves life, and translates poets and prophets worldwide, but "Necrologhi" does give us pause. She asks us to ask questions as ads bombard us and to, perhaps, even simply sometimes just close our eyes. I used to try that in the taxi, to step outside of the world being forced on me while I was a captive audience. Nadotti's perceptive and beautiful writing also gives us tools for freedom.