BACKGROUND

Unless you just returned from holiday in some ultra-remote region lacking newspapers, television or internet access (is there such a place?), you are aware that the government of Argentina defaulted on its external debt on Wednesday. A New York federal court decision provided the immediate cause of the default by a ruling that rendered illegal an agreement reached between the Argentine government and creditors holding over 90% of the country's external debt (details found here).

The principal litigant bringing the case against the government holds less than US$2 billion of the Argentine debt, which by comparison makes a tail wagging a dog seem a credible anatomical interaction. The principal litigant in the case, MNL Capital, never lent a cent to the Argentine government (nor to any other). It acquired its one billion plus of Argentine bonds on the re-sale market, purchasing at far below face value.

Depending on your source of [mis-]information, you will think that this default is 1) the result of a feckless, spend-thrift government failing to accept responsibility for its actions (argued for example, in Forbes), 2) the harbinger of deep economic trouble for the Argentines; and/or 3) the consequence of the predatory evil of vulture hedge funds.

Taking these three in order, they are 1) false, 2) probably false, and 3) true but not terribly important. The current debt of the Argentine government was accumulated before 2003, much of it under the disastrous presidency of Carlos Menem (forced to resign in 1999) and three short-term successors (Fernando de la Rúa, 1999 to end of 2001; Adolfo Rodríguez Saá, last two weeks of 2001; and Eduardo Duhalde, 17 months to May 2003).

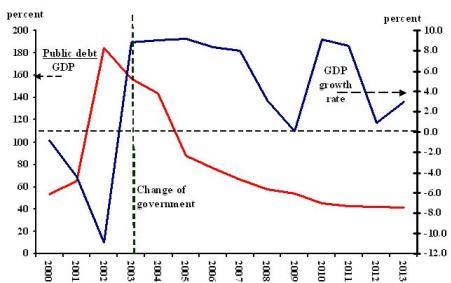

The massive debt accumulation (see chart below) resulted from the hapless attempt to maintain a one-to-one exchange rate between the national currency and the US dollar via a "currency board". This neoliberal bright idea legally links the amount of national currency in domestic circulation with the US dollars held by the central bank (in this case, the Banco Central de la Republica Argentina).

By the rules of this bone-headed currency "regime", the national money supply must fall when US dollars flow out of the country (for example, if there is a trade deficit or capital flight). Contraction of the money supply invariably means contraction of the real economy. To avoid this, prior to May 2003 the government (under its revolving door of presidents) borrowed US dollars through sales of public bonds, driving the public debt up to almost 200% of national income (measured on the left hand axis of the chart..

This debt was not accumulated in pursuit of "populist" expenditures by a fiscally irresponsible government. On the contrary, not a cent (centavo) of the debt funded any public service or brought any benefit to people in Argentina. To the extent that the foreign currency acquired by the bond sales stayed in Argentina, it sat idle in the Banco Central. And when this extraordinarily misconceived and mismanaged currency regime inevitably collapsed, it brought the entire economy down with it, a decline of almost 5% in 2001 and 12% in 2002 (read from the right hand axis of the chart), plus runaway inflation that climbed over 100% during these years.

Public debt and GDP growth in Argentina, 2000-2013

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators 2013.

In the wake of this disaster generated by the neoliberal currency regime, Nestor Kirchner won the presidential election of 2003, succeeded by Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner 2007, who was overwhelmingly re-elected in 2011. Becoming president after the end of completely discredited neoliberal governments, Kirchner abandoned the "currency board" system and disowned the debt accumulated in a foolish attempt to sustain it.

WHY GOVERNMENTS DEFAULT

The Argentine debt default this week, which I discuss in more detail in a subsequent article, demonstrates a general principle -- most sovereign debt defaults are not the result of mismanagement or wild spending by sitting governments. Two centuries of debt "refunding" shows there to be at least three major motivations for defaulting on sovereign bonds unrelated to excessive public spending

First, we find many examples of repudiation of debts because of the dubious circumstances of their accumulation under previous governments, and Argentina is an obvious example. A more extreme example is the cancelling at the 1953 London conference of the external debt of the Federal Republic of Germany (held over from the Nazi regime).

Second, global economic and political shocks can make it impossible for a government to service its debt (an old but excellent source is the 1973 book by Henry Bittermann). Obvious examples are the debt defaults by Latin American governments during the 1930s (due to a sharp fall in primary product prices) and the 1940s (collapse of international trade due to war).

Third, and being played out now in the euro zone, is public sector nationalization of private debts. As I show in my new book, during 2009-2010 the Spain government, previously with the lowest debt-to-GDP ratio of major EU countries, refinanced all its failing banks. This created both an unsustainable fiscal deficit (where before it boasted a surplus) and a public debt it could not finance. None other than the Pinochet regime in Chile had pioneered this particular path to debt disaster in the early 1980s under pressure from the US government (in value the largest nationalization in Chilean history, far larger than anything the socialist Salvador Allende had done).

A WAY OUT

All this leads to an obvious conclusion -- debt default serves as the solution to an otherwise intractable problem, an unsustainable foreign depth. The problem is not default, the problem is the absence of an international mechanism to bring it about in an orderly manner. But the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development has proposed such a mechanism, which I discuss in the second part of the Argentine Default story.