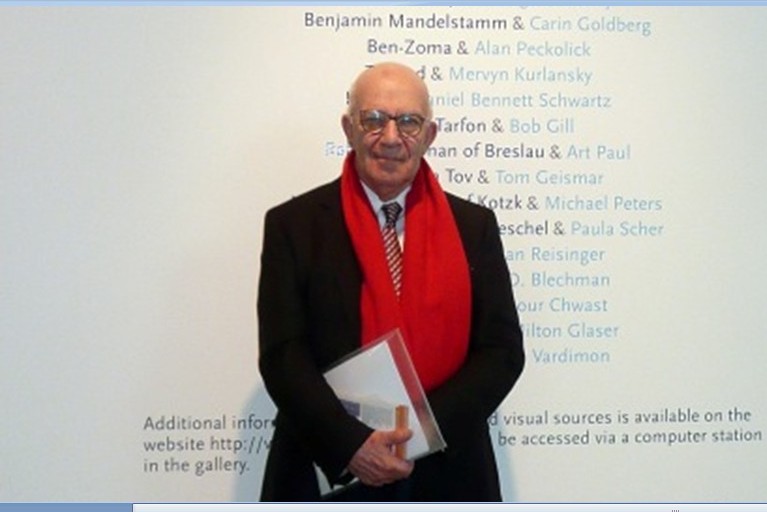

Arnold Schwartzman, the artistic director of the "Voices & Visions" program whose first set of 18 posters by world class graphic artists illuminating quotations from illustrious Jewish personages is now on view at the Skirball Cultural Center, is also one of the most accomplished designers and documentary directors of our times, is a story unto himself. Recently, I spent a few very companionable hours at Schwartzman's LA home as he shared some of the details of his personal journey and professional career.

As Schwartzman related, he was born in modest circumstances in London's East End. His mother was born in England, and his father had arrived as a young child from Lodz, Poland. His father worked as head waiter at London's Savoy Hotel. However, during World War II on the first day of the Blitz, their home was bombed. "We actually had to be dug out of the rubble," Schwartzman recalled. His parents survived, but he was evacuated to the countryside for the duration of the war.

After the war, his parents moved to Margate, a seaside resort that had been evacuated during the war. Seizing the opportunity, they started a rooming house, which in turn they traded up to purchase and run a small kosher hotel. (Coincidentally, it had been used at one point during the war to house the children of the Kindertransport.) Schwartzman is currently at work on a documentary about Margate.

Recalling his war-interrupted childhood, Schwartzman said, "I had an almost nonexistent formal education. I taught myself to read and write. What I liked was to draw. My parents didn't know what to do with me. They wanted me to go into the hotel business. I wanted to draw. So I went to art school."

Military service followed. Schwartzman was posted to the DMZ in Korea, where his chaplain was Rabbi (and later author) Chaim Potok. Many years later, Schwartzman asked Potok to write the introduction to his book, "Graven Images."

After military service, Schwartzman found work as a graphic designer, first in television, then in advertising as a creative director. "My major account was Coca-Cola," Schwartzman said, recalling that, "I got the Who to perform for our commercials." From advertising he became design director for Terence Conran's company, but managing people didn't appeal to him so he went off on his own.

A friendship with famed Hollywood graphic designer Saul Bass, who was in London at the time working on his own feature film, "Phase IV," led to Bass calling him to say: "How about you come to LA to be my design director." Schwartzman demurred but Bass was so enthusiastic and insistent that Schwartzman finally agreed. Within three months, he and Isolde, his second wife (who is also his production partner and manages all the logistics of his projects), had moved to Los Angeles - this was 1978 -- and they've been here ever since.

Schwartzman liked Los Angeles, but working for Bass? Not so much. "Once again, it was a mistake. I was running a studio, managing lots of people but not doing as much design." After six months he resigned. Bass took him out for a drink, and asked: "What are you going to do now?" Bass told him that just that morning he'd got a call from this new organization, the Simon Wiesenthal Center, to do a 15-minute film for them. Bass had imagined they might do it together but as Schwartzman had quit, he'd turned them down. A few minutes later, Bass said, "You're not doing anything now, why don't you do it?" That was the start of "Genocide."

What began as a short 15-minute film for the nascent museum took more than two years and involved research in archives in West Germany, France and at Yad Vashem in Israel. While in Jerusalem, Schwartzman was able to contact British historian Martin Gilbert, who also happened to be there. "Within months he wrote a fantastic script." The Wiesenthal Center was able to get Elizabeth Taylor and Orson Welles to narrate. Schwartzman was able to get Elmer Bernstein to do the score.

They originally conceived of having multi-projectors telling the story -- eventually 21 in all, coordinated by computers. When they finally screened the film, the response was so favorable that one of the viewers, Barry Manilow, suggested that if they put it together as being disseminated from one projector, then it could be submitted for the Oscars, which they did just in time -- and won the best documentary feature Oscar for 1982.

Schwartzman also regaled me with an anecdote about Simon Wiesenthal, whom he got to know during the making of "Genocide." Once when visiting Wiesenthal's overstuffed office in Vienna, Schwartzman spied a card file bursting out of cabinet, marked "M". Is that for Mengele? Schwartzman asked. "No," Wiesenthal explained, "It's for 'Meshugges.' You wouldn't believe some of the letters I get!"

Schwartzman consulted on several more films for the Wiesenthal Center over the years, including Echoes That Remain (1991) and Liberation (1994).

Another incipient organization, the Skirball, asked Schwartzman to consult on the graphic design of their initial installation, which included Jewish timeline panels as well as a kaleidoscope room of Jewish images."That was fun putting that together." Since then, Schwartzman has also consulted on other exhibits for the Museum of Tolerance.

Since 1996, he has designed many key elements of the Academy Awards, including posters, trailers and programs both for the award ceremony as well as the Governor's Ball. In 2010, the Cunard Line commissioned Schwartzman to paint two murals for their new "Queen Elizabeth" ocean liner.

Which brings us back to "Voices & Visions" exhibit. What was supposed to take four months, took 18. A lucky number in Jewish lore. Lucky, I would say, for "Voices & Visions" -- for Schwartzman proved to be not just a master designer for the poster initiative but also a master among designers.