The box office success of the film Sicario, which has grossed over 50 million dollars as of Oct. 18, seems to reflect the public's taste for violence and drama, especially at the border. Yet, how much do we really understand about the realities of those living in that space? How do we begin to understand the reasons that are driving so many Central American and Mexican women and children to try to reach the United States? How do we go beyond the narratives that continue to center on narco criminals while rendering their victims invisible? How do we listen to the stories that have been silenced and the names of the forgotten?

These questions are at the foundation of Alma Leiva's and Adriana Corral's artistic production. For these two emerging US Latina artists, art becomes a medium for challenging dominant narratives about narco violence by raising awareness about the toll that it takes on individuals, families, and communities. Above all, they uncover the violence exerted against women and children, its silenced innocent victims. It's practically impossible to remain unmoved by their work because we find ourselves in front of "arte comprometido" (engaged art), a type of art that addresses serious human rights violations and promotes social justice in two of the most violent cities in the world: San Pedro Sula, Honduras, and Ciudad Juárez, México.

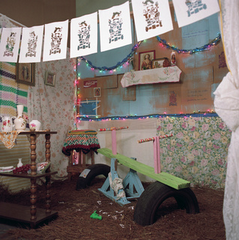

Alma Leiva (b. 1975) grew up in San Pedro Sula and migrated with her family to the US at the age of 14. Time and distance haven't severed ties to her homeland. Today, much of her art is inspired by the conditions that shape the daily lives of San Pedro Sula's inhabitants. In the series titled "Celdas," her installations and photography aim to uncover the effects of violence on the domestic environment. Each photo/installation is conceived as a memorial to specific victims of violence.

Though not entirely obvious to the average observer, each photo/installation incorporates elements from the crime scene it memorializes. Possibly unaware of the exact meaning behind it, the observer is met with a scene that oftentimes proves disorienting: a swing set, a see-saw, a mini soccer field, or a beach chair and umbrella in the middle of a small and humble living room. Playful elements decorate the picture -reminders of an innocence long lost--as well as daily objects (table, chairs, lamps, etc.) that emphasize the home.

The contrast between the home setting and some of these "dissonant" objects forces us to reflect on their contrast. By bringing outside elements into the domestic realm, Leiva achieves various results: she humanizes the victims of narco violence; conveys the sense of entrapment that results from rampant violence; and demythifies the home and other spaces we associate with the family (beach, school, play ground, soccer field) as safe havens from violence.

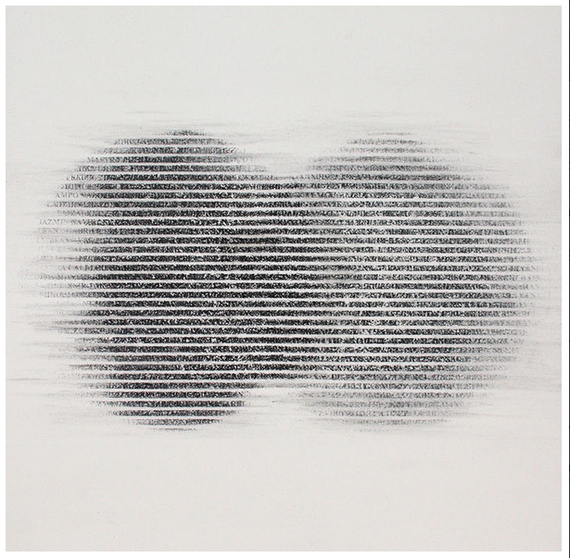

A similar consciousness-raising project can be found in the installations and graphic art of Adriana Corral (b. 1983). Born and raised in El Paso, Corral's engaged art has focused on the effects of violence at the border, especially the femicides in Juárez. Through a mixture of performance, ritual, and graphic art, Corral denounces the cycle of violence fueled by narco-terrorism and the state, as well as the impunity that guarantees the continuation of that cycle. Her performances often involve typing lists of victims' names and burning them or sometimes transferring them on a surface where they become blurred. The writing of each name honors the individuality and personhood of each victim - and thus serves to restore their humanity. Her installation "Impunidad. Círculo vicioso" honors both the "Ayotzinapa 43" (the student teachers disappeared in Iguala, Mexico, over a year ago) and the eight women found murdered in a mass grave near a cotton field in Ciudad Juárez in 2001.  By paying homage to these victims, Corral suggests that the violence exerted against them forms part of the same circle of violence that connects the State and narco violence.

By paying homage to these victims, Corral suggests that the violence exerted against them forms part of the same circle of violence that connects the State and narco violence.

Extreme violence permeates the lives of people in San Pedro Sula and Ciudad Juárez and once we understand that, we can begin to comprehend why so many thousands of women and children prefer the risk of fleeing to the almost sure death that awaits them if they stay. Leiva's and Corral's art provides us a window into their reality.

Alma Leiva's and Adriana Corral's work is the focus of the exhibit "Counter-Archives to the Narco-City" at the Snite Museum of Art at the University of Notre Dame through December 13, 2015. The exhibit was curated by Tatiana Reinoza and Luis Vargas-Santiago.