A June 2015 art exhibit, "The Transformative Power of Art," at the United Nations headquarters in New York City, harnessed the universal language of art to convey an important message: "Our fragile Mother Earth faces the devastating consequences of climate change, a defining challenge of our time." The exhibit also included sixteen portraits of people from all over the world who have "contributed to the common good of humanity in one way or another and have transformed the way we think."

The exhibit recognized the power of the universal language of art to transmit messages in a way that words cannot. Potent images remain embedded in our memory and return when triggered by life events. Art speaks to everyone -- regardless of age, religion, culture, social status, or education.

Historian Simon Schama, in his PBS series "The Power of Art," reminds us of the unique power of art to impact our thinking. He cites Pablo Picasso's huge mural Guernica, which depicts the horror and atrocities of the Spanish Civil War: "Guernica was art's cry of pain against modern savagery."

Powerful art images can forever mediate the way we see the world. While some images inspire, convey truth, and expose injustice, others can brainwash us with destructive distortions and false ideologies. Some artworks can cleverly present positive inspirations and at the same time subtly propagandize destructive ideologies.

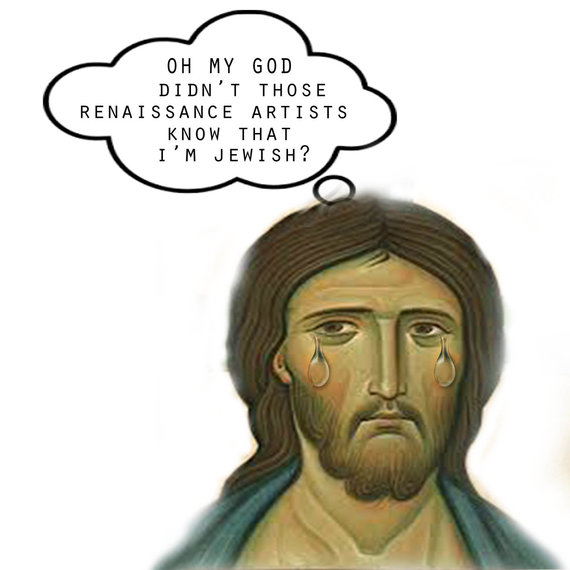

That is the case, I discovered, with Renaissance images of Jesus, his family and followers. In one respect a vast trove of Renaissance artworks inspire devotion and intensify faith in Christianity. On another level, though, they falsify biblical history and reinforce the divide between Christians and Jews, which has had lethal consequences for Jews over many centuries. The falsifications were all the more compelling because they were made subtly, by omission. What has been omitted is Jesus' Jewish identity. You can walk through gallery after gallery in museums around the world, as I have, and you will rarely see any evidence that Jesus was a Jew or had any connection to Judaism or to the Middle East where he was born and where he preached. Indeed, he is typically pictured as Northern European in appearance, with fair skin, blond hair, and blue eyes. And you will likely find him and his family and followers in regal attire, in palatial Renaissance settings, surrounded by symbols of a religion -- Christianity -- that didn't exist during his lifetime.

This imagery negates the undisputed fact that the Jesus of the Gospels lived and died a practicing Jew. Although his life and teachings inspired a new religion, which became an organized Church more than three hundred years after the crucifixion, one would expect that his connection to Judaism would at least be hinted at in these artworks.

Jesus' dedication to Judaism was not portrayed in Renaissance artworks for several reasons related to the evolution of Christianity as it emerged and separated from Judaism. But that doesn't explain why modern art historians, critics, and curators maintain the deceptions and falsification of biblical history. These art professionals analyze the most minute details of paintings, even using advanced technologies, but ignore the most glaring feature: the falsification of biblical history that can be seen with the naked eye.

Art professionals casually dismiss the distortions as artistic license in the service of the Renaissance style of contemporizing images. Furthermore, some art experts have told me, "everyone knew that Jesus was Jewish -- it was in their bible in the Gospels." If Christians had read the bible that would have helped correct the distortions but still not justifying the artwork falsifications.

The unfortunate truth is that despite loving their bible few Christians read it for well over a thousand years. For one thing, the Church discouraged Christians from reading the bible on their own. For another, relatively few bibles existed. Through the Middle Ages and early Renaissance copies of the bible were individually crafted by skilled scribes. Each copy was beyond the means of commoners (equivalent to as much as $100,000 today). Moreover, the bible was written in Latin, a language that virtually no one in the general population could read or speak. Well over ninety percent of Europeans were illiterate. Even many of the clergy couldn't read the Latin bible. And translating the bible into native languages was strictly forbidden. As late as the sixteenth century William Tyndale was burned at the stake for his English translation--and not because it was a bad translation. As much as 60 percent or more of today's King James version is Tyndale's translation.

So how did commoners and others learn about Jesus and Christianity?

Their information came largely from three sources, all of which were heavily tainted with distortions and propaganda. From priests, monks, and nuns the population heard stories that focused on miracles, devotional themes, the suffering of Jesus on the cross, and the resurrection. The Jewish Jesus of the Gospels was absent from these teachings. What was included, especially during Easter, was the charge that the Jews were enemies of Christianity and that they killed Jesus - a claim that conveniently ignored the fact that all of Jesus' followers were Jews and that there would be no Christianity if not for these Jewish followers.

The two other major sources of information about Jesus and Christianity were art forms: stained glass windows and paintings. These artworks conveyed even more constricted information about the life of Jesus. Paintings by the great masters spanned hundreds of years and presented Jesus, his family, and followers as Renaissance-era Christians with no connection to their Jewish heritage and identities. Separating Jesus from Jews and Judaism provided a major encouragement for anti-Semitism, which was already embedded in European Christian society. This virulent prejudice was reinforced by the population's lack of access to more complete and accurate information about the Jewish Jesus of the Gospels.

It's not surprising that artworks mirrored propaganda, since the paintings were commissioned by the Church, the biggest patron, and the wealthy, who sought to impress the Church with their devotion to Jesus and the teachings of the Church. Jesus the Jew did not fit into this illusory world.

It's puzzling that art historians continue to ignore the anachronisms and propaganda that were built into Renaissance religious art. These factors were not harmless. Hundreds of thousands of Jews were slaughtered during the Middle Ages and Renaissance based on false teachings to which the distortions in artworks contributed.

In response to these criticisms is art experts' dismissive notion that "nobody believes that stuff [about Jews] any more," a claim that flies in the face of the current worldwide rise in anti-Semitism. In fact, according to a 2013 Anti-Defamation League survey, 26 percent of Americans still believe that the Jews killed Jesus. And that number may well be higher, because many respondents were probably loathe to admit they held such a politically incorrect view. And those numbers are surely greater in other parts of the world.

Why are art historians so reluctant to admit that biblical distortion was widespread in Renaissance artworks and that the distortions thus fueled the spread of anti-Semitism? One reason may be their romanticized embrace of the Renaissance -- an almost orgasmic ecstasy over the resurgence of literature, art, and natural science resurrected from classical Greek and Roman times, while ignoring the bigger picture of life during the Renaissance. When I suggested this to one prominent art historian, he chastized me: "How can you criticize the Renaissance -- it restored humanism and beauty."

This infatuation fails to take into account how the vast majority of Europeans experienced that period. The Renaissance emerged slowly. Europeans didn't wake up one morning and rejoice: "The dark ages are over -- the lights are back on." What's more, the Renaissance, especially for the first few hundred years, benefitted only a tiny portion of society. Today's gap between rich and poor -- the 99 percent vs. the 1 percent -- was even greater through the Middle Ages and Renaissance. But more defining of the difference between now and then was the difference in living conditions between rich and poor. The vast majority of the population lived under such dreadful conditions that a modern-day homeless shelter would seem like Shangri-La.

Historian William Manchester, in his book A World Lit Only by Fire: The Medieval Mind and the Renaissance, gives a grim picture of peasant life in the 1500's. He quotes priest and social critic Desiderius Erasmus, who actually examined the huts of commoners, and reported: "Almost all the floors are of clay and rushes from the marshes, so carelessly renewed that the foundation sometimes remains for 20 years, harboring spittle and vomit...remnants of fishes and other filth unnamable." Manchester adds that the centerpiece of the room was "a gigantic bedstead, piled high with straw pallets, all seething with vermin." Everyone slept there, including animals. And this particular gruesome setting was "the abode of prosperous peasants." Their neighbors lived in worse circumstances. During the one-year of famine after the usual three years of harvests, hunger and extreme poverty were widespread. Peasants, Manchester reports, were forced to sell all their belongings, including their clothing, which often reduced them to nudity. In the most difficult times "they devoured bark, roots, grass, even white clay, and cannibalism was not unknown." Life expectancy for men was about age forty. For women even less. Manchester relates a popular Renaissance story that is emblematic of the commoners' living conditions. "A peasant in the city who, passing a lane of perfume shops, fainted at the unfamiliar scent and was revived by holding a shovel of excrement under his nose."

Living under these appalling conditions was hardly conducive to appreciating the "humanism and beauty" of the Renaissance.

Adding to the misery of the masses, just as the Renaissance was gaining traction the black plague swept across Europe in 1347 wiping out a third of the population. The resulting poverty, decimation of families and communities, and the unimaginable grief generated by the plague reverberated for generations. While the plague did not discriminate between social classes it found more welcome hosts in the squalor of peasant communities. Many of the wealthy were able escape to the fresh air and cleaner environments of their country estates.

Author and Renaissance historian Alexander Lee warns that "it is so very easy to be seduced by the beauty and elegance of the art and literature of the Renaissance, the ugly side of the period is all too easily forgotten and overlooked." The title of his book expresses the other side of the Renaissance rebirth of culture: The ugly Renaissance: sex greed violence and depravity in an age of beauty.

Another reason art historians and others in the art world have glossed over the anachronisms in Renaissance artworks is that they are considering the distortions out of their proper context. Put them back in context and they would be jarring. I came to that realization after viewing the National Geographic documentary Killing Jesus, based on Bill O'Reilly's book of the same title. Unlike many other films about Jesus, this film presented realistic portraits of Rabbi Jesus (he's called Rabbi throughout the film) and his fellow Jews as Semites living in crude dwellings in a rural village. Now imagine if in one of those scenes (like the one below) you saw Jesus preaching to a "multitude" of fellow Jews or in a synagogue where he regularly worshiped and read form the Torah -- -and all the Jews were holding crucifixes, the feared and loathed symbol of Roman persecution. It would look ridiculous -- and would surely invite criticism of the anachronism.

Yet, the image of Jesus and other first-century orthodox Jews with crucifixes is common in Renaissance paintings.

Baptism of Christ by Andrea del Veracchio-Wikimedia.. Holy Family Flight to Egypt by Fra Bartolomeo-Wikimedia

The propaganda message in these artworks is clear: Jesus, his family, and disciples are Christians, far different from the dark menacing Jews who killed Jesus. To emphasize the "Christ Killer" point, crucifixion scenes have frequently pictured Jews mocking Jesus. All these propaganda messages are patently false and indefensible against documentation in the New Testament. But recall that the general population of Christians could not read the bible. Had they been able to they would have met the Jewish Jesus.

`

In the light of Pope Francis' bold statement that "inside every Christian is a Jew," I think it's time for art historians, curators, and critics to perceive Medieval and Renaissance religious paintings in a broader context. It's time for the experts to acknowledge the propaganda value the falsifications had in reinforcing anti-Semitism. And to recognize that Renaissance artists and patrons invented a Christian Jesus and ignored the fact that Jesus of the Gospels was Jewish to the core.

The truth would surely contribute to closing the historic Christian-Jewish divide while taking nothing away from the magnificence of the artworks.

Bernard Starr, PhD, is Professor Emeritus at the City University of New York (Brooklyn College). His latest book is "Jesus, Jews, and Anti-Semitism in Art: How Renaissance Art Erased Jesus' Jewish Identity and How Today's Artists Are Restoring It." He is also organizer of the art exhibit "Putting Judaism Back in the Picture: Toward Healing the Christian/Jewish Divide."