"I think what we are seeing and relearning with the 'Black Lives Matter' and 'Say Her Name' movements is that a lot of the issues and questions that we thought were settled from the 1960s through the 1980s were not quite settled. The structures that created and maintained oppression in the past are far too often still in place and we need to keep talking about them. We also need an intergenerational dialogue where different generations tell each other what they see. One of the greatest things about teaching is that I learn so much from my students. I want to hear what younger people have to say and what they see, and my hope is that they will want to hear what I have to say and what I see." So maintains Columbia University art historian Kellie Jones.

Maybe part of Jones's great admiration for the 'Black Lives Matter' and 'Say Her Name' movements comes from the fact that her parents, acclaimed writers Amiri Baraka (formerly known as LeRoi Jones and Imamu Amear Baraka) and Hettie Jones, taught her from very early on that she had to stand her ground and insist on being heard. "In a family like the one I was born into," Jones explained, "you had to find your voice very early on and be in the mix. My parents' examples were of speaking up and speaking out."

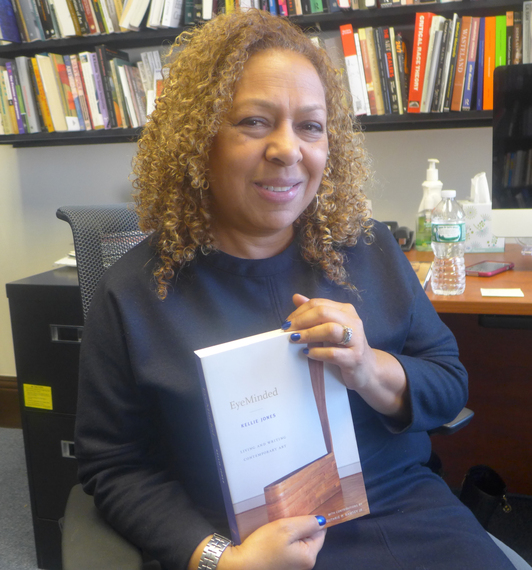

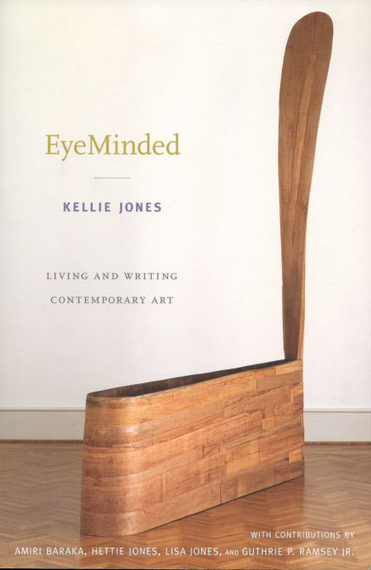

The outcome of all of this is a family of writers and thinkers. Indeed, Jones's recent collection of essays, EyeMinded, Living and Writing Contemporary Art, sees various family members (including her husband, musicologist Guthrie P. Ramsey Jr) contributing pieces to the publication. The end result is a compendium largely written by Jones herself, but with essays by her mother, father, husband, and her sister who is as well a published author. One gets the sense, as one reads the collection, that they are listening to a family explaining itself to itself even as it engages with the outside world. It is an engaging read. But for Jones, the collection is so much more than that. "In my family, books are a cause for celebration and EyeMinded was no different. In so many ways EyeMinded was a prescient book because my father would die only a few years after its publication. For me, this collection has since become a way to try and memorialize all the conversations that we had as a family."

Kellie Jones was born in New York City. "Growing up in New York, on the Lower East Side, was just fantastic because you learnt from very early on that the world is just a very large place and the world is comprised of many different kinds of people," she noted.

She would go on to attend LaGuardia High School of the Arts with the likes of singer Curtis Blow and the actor Alva Rodgers. Though she was a visual artist at LaGuardia High, what she really hoped to become was a diplomat, because she liked the idea of travelling the world. Eventually she would go on to Amherst College in Massachusetts, arriving at the time when the school was just going co-ed after being an all-male institution. She remembers that time at Amherst as being particularly difficult because she was integrating and going into an all-male institution.

Yet, it was at Amherst that Jones would start to find her way. "When I was at Amherst there were only two types of artists -- artists were either white or they were dead. Yet I knew this to be just plain wrong because I grew up with the likes of Norman Lewis and Camille Billops. This started me thinking that there might be a place for someone who is a writer and curator for artists of color. And the more I thought about it, the more I realized that art and diplomacy shared a lot in common, for at that time I was still thinking about being a diplomat. Soon I realized that with art I could travel, speak to people in different countries, and while for me art is not necessarily or only a mediator, it is certainly a way to talk across different countries and cultures."

From Amherst College Jones would go on to work as a curator at several notable institutions including the Studio Museum in Harlem, The Jamaica Arts Center and the Walker Arts Center. At the Studio Museum in Harlem she was in charge of curating a collection of art amassed by the State of New York but overseen by the Studio Museum. But even as she made her way as a curator and started participating in such important shows as the São Paolo Biennial in Brazil, she started thinking about going back to school to get an advanced degree. Finally, she narrowed her range of interests between getting an MBA or a PhD. Eventually, because she loved the world of ideas, the PhD won out. Her thinking at the time that she went off to do her PhD at Yale University was that she would come back to the world of museums. But increasingly she found that she liked "living in the world of ideas; whether it is in the form of new thoughts from students or great colleagues."

From academia Jones also felt that she could best tackle and critique certain structural issues facing, in particular, artists of color. "What we need to understand is that the culture of patriarchy and white supremacy continues to play an important if not dominant role in the world that we live in," she pointed out. "What I appreciate so much about the movements that have sprung up in recent times is that they are comprised of people who want to work to get rid of these obstacles and to reform these structures. It makes me incredibly optimistic that people, young people in particular, are so passionate and engaged!

"Institutional structures do not come down easily, however, and this is the case with even the movements and institutions that we admire. Why is there a need for the 'Say Her Name' movement, which lists the name of black women killed by police in the United States? Because there is an element of sexism in the 'Black Lives Matter' movement. Of course the 'Black Lives Matter' movement did not set out to be sexist, and if you speak to activists they will tell you that more than anything else, they set out to draw attention to the more visible cases of police brutality, which are the cases against black males. So the question then becomes: Why aren't the deaths of black women by police officers equally visible?

"And that is what I mean that old structures remain in place, and that is why I am so emphatic about the need for a cross-generational dialogue because we can tell each other about what we have seen and what we know. And that, too, is part of the reason why I love teaching so much. I get to take the students into my world and the students get to take me into theirs."

Because our conversation revolved so heavily around art as a means of activism and around the black body being a site of contention and contestation, I wondered about works by artists of color that were not specifically or primarily activist. Where, I wanted to know, was the work of, for example, the black body as desiring and in love?

To see this work more clearly, Jones told me, one might have to take the body out of the work. She pointed to what abstract artists like Jennie C. Jones, Norman Lewis, and Jack Whitten have been engaged in, as an answer to my question.

But also in answering the question I posed, Jones pointed to the influential role of education. Curators and educators, Jones maintained, can help to drive these discussions. "What I would say to someone, particularly those interested in working on areas of the African diaspora, is that the doors are opening up more and more every day. More and more there is a need for curators and academics with this particular specialization. While it is not for everyone, the PhD is not a useless degree, and I think of how many more opportunities I have gotten because I chose to get a PhD in art history. So I really would like to put it out there that now, more than ever, there is a place for art historians working on African and African diaspora arts."

In so far as how artists, particularly artists of color and women artists, can begin to find their way into the art world, Jones has some specific recommendations: "Perhaps the first thing you should do is get a website. Secondly, meet as many people as you can, and then show your work wherever you can. Art, as the wonderful artist Lorraine O'Grady so aptly puts it, is a long-distance game. For artist David Hammons, art is an old man's game. It is easy to lose sight of this with a few artists getting really famous right out of graduate school. What I would say to particularly women-of-color artists is not to lose faith. Things have changed somewhat and as more and more people level critiques at museums as to the artists they have in their collections, and the artists in the exhibitions they put on, things are set to change even more. I would tell artists to go to lectures, meet people, put yourself out there. Meet successful artists and ask them questions about how they did it. Never stop trying."

Until next time.