I am an architect who makes art. My education and practice as an architect have informed what I see, the way I think, and what, why, and how I make art.

This is a look at my art through my architect's lens. I aim to expose facets of meaning according to the Vitruvian triad of structural integrity, beauty, and utility.

Structure

Architects think in terms of space and form, and structure is at the core of the architectural artifact.

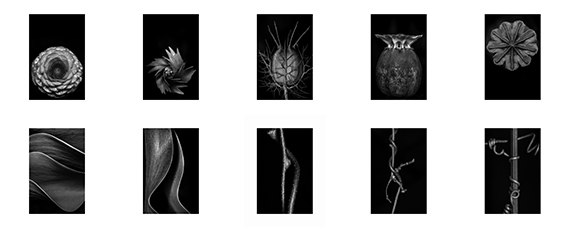

My Untitled project is a series of photographs of living plant elements photographed in parks and gardens. The series' parameters--defined and treated as structural elements--include print color, format, size, and borders. These shared parameters preserve the series' coherence and integrity and serve as a sculptural basis for my art by holding and framing each image.

I obscure backgrounds to isolate subjects from their contexts. I strategically position my subjects within white frames to evoke feelings like withdrawal, sensuality, and love or sensations like gravity or levitation. The vertical spine of a Gingko Biloba leaf stretches sensually along the frame. The circular form of an Opium Poppy crown hovers in the upper part of the frame. I seek out and use symmetry to highlight imperfections or particularities of pattern and shape. Angling a subject's core axis up-down or right-left shows up natural asymmetries and imperfections along it, such as the minuscule irregularity on the rim of a Paphiopedilum Orchid's lower lip.

Photographs shown together are arranged in a horizontal line sometimes broken into vertically-juxtaposed equal sequences. The series is to be read from left to right and top to bottom, as is Western text on a page. This arrangement brings out similarities and progressions in form--usually from the circular to the linear--and feeling. The images' positioning guides viewers from and allows them to compare one to the next.

Beauty

As an architect and artist, I strive to design dwellings and make art that are moving as well as aesthetically appealing. The Untitled series is an attempt to reveal the beauty intrinsic to each subject. Subjects are mostly tiny, simple plant elements found in ordinary, natural settings that I exalt by turning them into art that celebrates them. Plant elements are either shiny, fresh, newly-germinated stems, buds, and blossoms or weathered, withered boles, twigs, and leaves. The latter are reminiscent of Wabi-sabi, the traditional Japanese aesthetic that honors transience and imperfection in nature.

Art results from the act of making an image beautiful and moving. To make my subject beautiful to the viewer, I polish and emphasize form with light and draw from a palette that ranges from the pure white of a wet surface catching the light to the rich black of deep depth of field. I print digitally on thick matte Hahnemühle paper because its fine, smooth surface creates high-quality prints that emphasize fine tonal graduations. Carefully-placed planes of focus form a tonal spectrum whose span expresses sharp foreground detail as well as soft background. The end result is an image that is compellingly beautiful.

My interest in architectural structure followed naturally from an earlier fascination with organic structure. I had studied the organic unit, the cell, because I was curious about how singular characteristics could account for such diverse structures as hair and bone. Now, when I look at a black-and-white print of a Gingko Biloba leaf magnified six times, what I see is architecture: structure, form, and texture that remind me of Oscar Niemeyer's magnificent reinforced-concrete edifices. It is clearly the leaf's organic structure that determines the gracious--whether sophisticated or immature--way in which it hangs from the stem.

Beauty also resides in the metaphor that an image may evoke. I do not give my photographs titles, preferring to allow viewers' minds to drift and form visual associations. My photographs do, however, have private nicknames referring to the personal metaphors that they evoke in me. Discerning symbols and identifying visual metaphors is part of my creative process. While I am taking a photograph, I may identify, seek to embed a discerned symbol or metaphor. For example, when I saw and felt a Madonna and Child in a minute germinating sprout, I worked on the image until it conveyed that metaphor to me. I am nevertheless conscious that, like Rorschach inkblots, visual metaphors are infinite in number, uncontrollable, and can only be suggested to others.

Utility

Whereas an artifact's utility or function is set in its programming, its function, when designed by an architect, can go beyond programming to encompass human experience of both exterior object and inner space.

When presenting an architecture project, I first lay down facts about it. I lead the client around the outside of the edifice, highlighting its features and surroundings, and then move inside and through the plan from the entrance to any upper rooms, all the while pointing out how one experiences the inner spaces in concert with those visible through openings. "La promenade architecturale," this movement through the building, and the resulting sequence of images unfolding before the observer, was central to Le Corbusier's architectural design. That concept shaped his buildings interiors and exteriors. Our physical experience of any architecture and art engenders emotions that in turn affect our emotional response to our environment.

Le Corbusier collected natural objects and used them to draw up the natural laws that formally influenced his design of architecture objects, whether elements like stairways or entire buildings. He wrote: "Around 1928 I felt a desire to expand my pictorial vocabulary and became interested in what I called objects of poetic reaction (objets à réaction poétique), any number of ordinary items that contain, summarize, and express the laws of nature, events understood as symbolically significant, etc. After that I began to work on the human figure." (Le Corbusier, L'Architecture d'Aujourd'hui, Special Issue, April 1948, p. 45).

The purpose of my Untitled series is not to inform my architecture but to draw attention to and elevate the small but not insignificant plant elements encountered in daily life. A walk through the series is intended to provide an inner experience that will bring about a renewed sensitivity to the natural world. Magnifying little details of life that would otherwise go unnoticed exposes monumental beauty, triggers amazement, and revives from within. By inviting contemplation, my art transcends its subjects.

Architects strive to design works that are internally and externally meaningful. We are concerned with an edifice's essence and also with its cultural and historic context. Similarly, my Untitled series, by focusing on subjects' structure and beauty, is an ode to natural forms that seeks to compel the viewer to see the world with new eyes, to feel it from within.

What makes my Untitled series distinct is my use of digital technology to photograph living plants in their natural environments. Freed from the studio, I observe how the fall of natural light on subjects defines their form, and faced with the elements, like wind and sun, I take multiple photographs of a single subject until I get it right.

In exploring the visual metaphor in living plants, I am building on the legacy of Edward Weston's still lifes; and my use of contemporary digital tools furthers the macro photography tradition of Karl Blossfeldt by making high-resolution photographs of plant forms in nature. Unlike Hilla and Bernd Becher, I am developing a romantic typology of forms in which feeling is perceptible. In my ongoing Untitled series, I am constructing a progressive sequencing of form and feeling.

My education, training, and practice have shaped my senses. I do what I cannot help but do. Being a highly sensitive person and feeling things intensely has left me with the need to express my feelings. I accomplish that through my art.

More at: www.annaagoston.com