Leonard Bernstein has been hanging around again. He sat with uncharacteristic calm in a photo in the New York Times on February 4th that accompanied a piece about the newly expanded accessibility of the New York Philharmonic's historical archive.

The image, by a Times photographer, was coolly detached, catching Lenny as he waits for the start of a hearing on racial discrimination at the Philharmonic. It's 1969. He sits on a couch, eyes down, no baton or audience in view -- a guy caught in a story by daily photo-journalism. That news shot made me think again about other Bernstein photos I've been looking at lately.

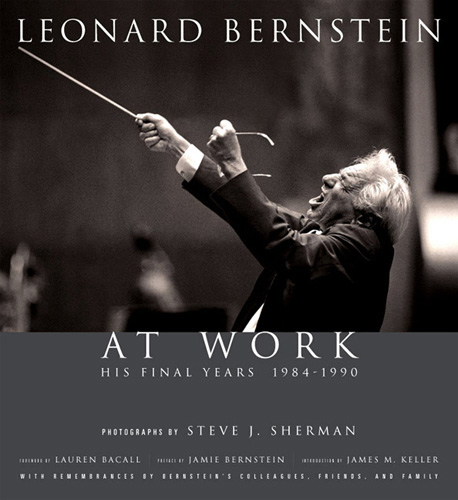

These more heroic images -- six years worth of them -- are by a photographer named Steve J. Sherman, in a recently published book called Leonard Bernstein At Work (Amadeus Press). At least, they seem heroic at first, photos to make their iconic subject shine. But are they the work of an icon-maker? Sherman took them as an official photographer for Carnegie Hall and the New York Philharmonic. They offer Lenny, glowing celebrity, lunging into space behind his baton, embracing a famous soloist, trading smiles with a socialite, accepting yet another award.

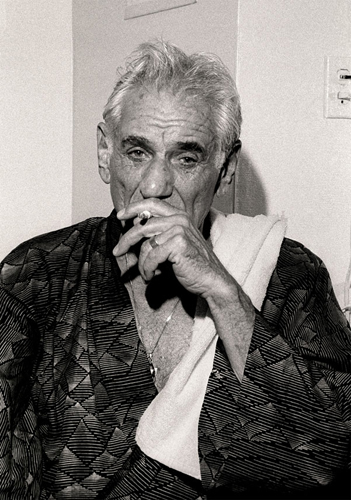

Look again, though, and these pictures start to haunt you. Shadows leak around the smiles, the deeply wrinkled skin, the steady but tired eyes. Even if you know plenty from reading about Bernstein's life-long inner conflicts, some of these pictures strip him to an almost violated nakedness. He cradles his scotch, sucks a cigarette -- almost always, the Bernstein cigarette. From this anti-smoking era, without relying on facile judgment, we suspect incorrigible self-destructiveness in the midst of success, wealth, fame. Asked once why he didn't quit smoking -- the quote appears in Sherman's book, beneath a photo where Lenny's heading offstage to use a Nebulizer to clear his emphysema-squeezed passages -- Lenny said, "Why don't you spank me? I'm a bad boy."

Sherman's account of Lenny's ever-present excesses remind one of other culture-permeating figures of the era -- Tennessee Williams, Marilyn Monroe, Marlon Brando, Jackson Pollock, Janis Joplin and others who harnessed, wrestled with, expressed, survived (or didn't) being a sensitive artist in an America that never gets past its conflicts about success, wealth and fame.

Even in some openly happy shots, his eyes seem anxious, adrift. Even in one award ceremony, the grin looks strained. For Sherman had a second, more secret enterprise, a surgical challenge to the image of the public man he celebrated. He carries an inner newsman. His story is a great artist's mortality. As Sherman says, all Bernstein's powers couldn't hide from a life that was "like five lives in one."

This becomes especially clear as we follow the photos into Bernstein's last years -- the book is sub-titled, "His Final Years, 1984-1990" -- ending with a farewell concert's last moments in Carnegie Hall. There are other pictures in which we glimpse exhaustion catching up with him. But here he's about to leave the world he's mastered. And worse, Sherman said in a recent interview as we looked at his pictures in his office-studio behind Carnegie Hall, Bernstein probably knew he was dying. His wariness of the future is palpable.

Ionesco's title for a play -- Exit the King -- works well.

The last photograph in the Sherman's book, the last he took of Bernstein, is this one, from March 7, 1990.

-- Photo: © Steve J. Sherman at www.stevejsherman.com--

"Lenny adored his ovations," Sherman says. "He loved the way the audience reacted to him. But, in this bowing sequence, those wonderful smiles you'd always see were replaced by this look."

He searches for the right word to do justice to Bernstein's expression. "I'd never seen it before. Nothing like it. This was his last performance at Carnegie Hall, the Vienna Philharmonic, Bruckner's Ninth Symphony. It was a kind of farewell. He conducted beautifully. It was vintage Bernstein, but when the ovations came, there was something changed about him.

"I didn't really know what I had when I took the pictures," Sherman continued. He explained how, generally, one "action" photograph is published as the main result of a concert photographer's work. The rest get saved, but aren't used. He stores these "outtakes" for years. He went back to his Lenny boxes to assemble an exhibit for a Bernstein symposium at Harvard in 2006. "I looked at those last pictures closely for the first time and stumbled on this sequence. I knew I'd found the story of this book."

Read from the beginning, however, the book's wide pages brim with euphoric moments that give context to the final bleakness. It covers years of Bernstein at full throttle, freezing moments of intense rehearsals, his adrenalin bursts in performances, a Bernstein enveloped in work with fellow musicians, composers. One also gets a backstage world, the super-star entourage, managers and publicists whose solicitousness and expertise at their roles mirrored the maestro's intensity. Yet, even amid this bustle, one can't forget that we're on the far side of a career's expansive arc. Some of the most candid-feeling images are of Lenny in dressing room, drained but elated after a performance, cigarette and scotch glass in hand. He's burned out but still burning.

Players whose quotes Sherman uses wondered at how unmistakably they saw the toll of the years in Lenny's face until he started to conduct and showed the volcano wasn't cold.

Leonard Bernstein in his dressing room just after conducting the Israel Philharmonic in Brahms's Symphony No. 1, on September 22, 1985

-- Photo: © Steve J. Sherman --

There are about 220 images in Leonard Bernstein At Work. Sherman draws quotes from many interviews with friends, orchestra players and soloists. Some were done by himself, many by his father, Robert Sherman, a well-known radio personality specializing in classical music. He includes some big ideas about life and art from a man who spent his days making music and many nights (he was a famous insomniac) reading literature.

"You should have learned, with any luck, to love learning," says a Bernstein quote beneath a Sherman shot of Lenny coaching young conductors. "Loving (yourselves, one another, your teachers, Keats, Euclid, Bach, Beatles) is the only way to genuine learning -- that is, learning that will always be part of you, always animating your mere existence. There is no other way."

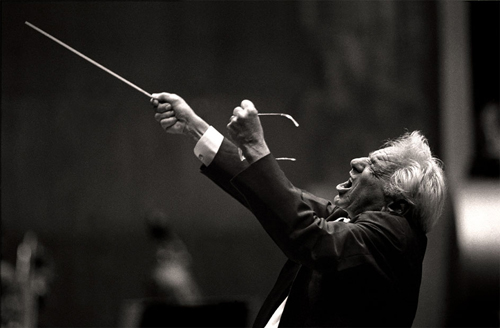

Several bursts of insight come from leading musicians talking about one of their own. "I found him to be my kind of conductor," says Itzhak Perlman, "somebody who choreographs his feelings about the music. Beating time, I find, is a secondary thing. Everybody beats time, but he really showed (the orchestra) in his movements, in his face, what he feels about the music... "

Photos of Bernstein conducting meet his pure physicality with an aesthetic that is all about movement. The photographer's favorite picture is the one on the cover of him leading the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, doing in Shostakovich's Seventh Symphony, the "Leningrad."

"That's my favorite shot because I think it captures all that he was in one shot. It is a picture of all-out commitment," Sherman says. And Bernstein's favorite Sherman shot graces the back of the book. It shows the conductor at the edge of movement, leading the Israel Philharmonic in the Ninth Symphony of Mahler. "He knew both pictures, but said he liked the one of him conducting the Mahler because he always saw pictures of himself with a wild intensity, the craziness, but this one showed quiet intensity. He looks like some kind of hawk staring out from under his eyebrows at the musicians. I've seen him conduct with those eyebrows," Sherman adds.

Bernstein conducting the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in the Shostakovich No. 7, June 24, 1988.

-- Photo: © Steve J. Sherman --

Bernstein conducting the Israel Philharmonic in the Mahler No. 9, September 21, 1985.

-- Photo: © Steve J. Sherman --

Sherman took his first professional Lenny shot in 1984. But near the start of the book, after the forward by Bernstein friend Lauren Bacall, after the moving preface by daughter Jamie Bernstein, come two surprises. One is an old but clear photo of a young Bernstein posing with a smiling woman at Tanglewood in 1948, 11 years before Sherman was born. It's his grandmother.

"I guess one could say that this photograph of Leonard Bernstein with my grandmother, the great pianist Nadia Reisenberg, taken by my dad back in 1948, proves that I knew Lenny at least eleven years longer than I've been alive," Sherman writes, in his own preface. Reisenberg was a highly regarded concert pianist and teacher at Julliard. This book reflects something of a genre-crossing dynasty in the service of classical music. The connections go deep. It is unmistakable, for example, how the expert but egalitarian feel for musical personalities in the son's photography mirrors the father's radio presence. The grandmother, too, is remembered by piano historians (I know one who easily talked for 45 minutes about her) for grateful memories among her students and her many radio broadcasts.

All this history knots into the moment when the young Sherman met Lenny for the first time. He was with his father at a Bernstein concert on a hot day in Connecticut, in 1974. Ten years later, his father invited him to the last day of Bernstein's recording session for West Side Story. He grabbed his cameras -- and that was the start.

"One of the biggest challenges to photographing Leonard Bernstein," Sherman says, "was getting around and through all these people who surrounded him. People would just push me out of the way to try to get closer. One challenge was staying where I needed to be to get the picture. Another was getting close to Lenny with a big camera and a big flash and being totally invisible. I needed to be invisible so he would feel totally natural around me. I wanted him to be just who he was."

How well Sherman succeeded is clear from the fiercely energetic, if sometimes heart-breaking human dimension of this book.

The sad wonder of turning its pages, in the end, felt like looking at a terrific Life Magazine climber on a late, shadow-filling descent of Everest.