Carrie spoke through narrow lips that looked like they were sewn on too tightly. She had the gravelly voice of a lifetime smoker, but her trembly tone and hesitant nature made her barely audible. She seldom talked to people during the support group, and if she did she never peered  directly into anyone's eyes. She usually sat near a corner of the room, always making sure to face the only door leading in or out.

directly into anyone's eyes. She usually sat near a corner of the room, always making sure to face the only door leading in or out.

Carrie was petite and jittery. The pale foundation she slathered on her cheeks and the thick black lines she drew under her eyes did not conceal her frailty. Her dry, bleached-blonde hair tapered sharply just below her shoulders. It hung in solid-looking clumps that, like the rest of her, seemed as brittle as icicles.

Carrie usually dressed in snug, almost colorless acid-washed jeans and plain, baggy, crew neck sweatshirts in creamy tones of pastel pink or yellow. In all those faint colors, she sometimes appeared as though she might fade away. The exception was her polished white-leather sneakers. They never had a single scuff or mark anywhere on them. The laces were pristine, too, and always double-knotted and tightened to an extreme.

Whenever I remember Carrie, I think about the control that we do and do not have over our lives and about how we often end up coping with trauma and illness in arbitrary ways. Carrie had the unbelievably horrible misfortune of being brutally raped by two different strangers on two separate occasions. I don't pretend to know how Carrie's tendency to practically bind her feet with those spotless, white laces helped her feel a tiny bit safer. Still, I would guess that this seemingly insignificant and maybe even maladaptive attempt at controlling her body gave her a small sense of security. I pictured Carrie using a vice in the morning to meticulously cinch her shoelaces and needle-nosed pliers at night to diligently untie them.

In our support group, they tried to reassure and empower us. With the best of intentions, they encouraged us to think of and talk about ourselves as "survivors" instead of "victims." Yet, when I look back at Carrie and consider how the unfathomable randomly happened to her not once, but twice, I have a hard time seeing how this distinction between victim and survivor helps. Both of those labels seem inadequate. They remind me of Zhang Longxi's observation in The Myth of Other, where he asserts that "artificial language systems arise from the desire to impose order on a chaotic universe." That Carrie survived and was still sustaining herself was incredible, but calling her a survivor and not a victim seems dismissive of her constant struggle and at the same time unrealistically demanding of her remaining reserves. And venerating her mostly non-existent agency and involuntary stoicism just feels disingenuous.

In our support group, they tried to reassure and empower us. With the best of intentions, they encouraged us to think of and talk about ourselves as "survivors" instead of "victims." Yet, when I look back at Carrie and consider how the unfathomable randomly happened to her not once, but twice, I have a hard time seeing how this distinction between victim and survivor helps. Both of those labels seem inadequate. They remind me of Zhang Longxi's observation in The Myth of Other, where he asserts that "artificial language systems arise from the desire to impose order on a chaotic universe." That Carrie survived and was still sustaining herself was incredible, but calling her a survivor and not a victim seems dismissive of her constant struggle and at the same time unrealistically demanding of her remaining reserves. And venerating her mostly non-existent agency and involuntary stoicism just feels disingenuous.

My tendency to recoil when people talk about "surviving" tragedy or "battling" sickness is not unique to Carrie's story. I feel uncomfortable when people use war and sports analogies in the context of illness or trauma. Recently, as I was trying to figure out why the "winning-the-good-fight" lexicon seems to chafe at me as it does, I recalled my father's bewildering decision to choose the doctor in the Hermès necktie. I had never been able to justify my father's strange calculus before, but somehow for the first time ever I realized that his baffling choice was a lot like Carrie's. Under very different but equally devastating circumstances, both my father and Carrie managed to create a tiny bit of solace for themselves by fixating on quotidian objects that had little to do with actually providing safety.

Unlike Carrie, my father was a tall, pompous, and outspoken man. He had a thick, dark beard that had once matched his eyes but had grayed significantly in his 50s. Sometimes, he spoke with a pretentious-sounding accent. He took pleasure in exaggerating the enunciation of uncommon words, and he often came across as unapologetically elitist and arrogant. He didn't realize that fast food restaurants do not employ waiters, until his youngest child was a teenager looking for a summer job. And, he prided himself on never having owned an uncollared shirt. Still, he could be charming. He enjoyed hosting friends and family in his home, always making sure to stock his bar and wine cellar with his guests' favorite drinks. Although I don't have a lot of happy father-daughter memories, when my father was feeling magnanimous, something about his broad smile and bright eyes made me feel at ease.

Unlike Carrie, my father was a tall, pompous, and outspoken man. He had a thick, dark beard that had once matched his eyes but had grayed significantly in his 50s. Sometimes, he spoke with a pretentious-sounding accent. He took pleasure in exaggerating the enunciation of uncommon words, and he often came across as unapologetically elitist and arrogant. He didn't realize that fast food restaurants do not employ waiters, until his youngest child was a teenager looking for a summer job. And, he prided himself on never having owned an uncollared shirt. Still, he could be charming. He enjoyed hosting friends and family in his home, always making sure to stock his bar and wine cellar with his guests' favorite drinks. Although I don't have a lot of happy father-daughter memories, when my father was feeling magnanimous, something about his broad smile and bright eyes made me feel at ease.

My father learned that he had cancer after a tumor in his gut ruptured and spilled out into his abdominal cavity. The on-call doctor, who performed the emergency surgery that saved my father's life, happened to be a surgeon in chief at the hospital. Not only did this physician have a distinguished title, he was also a European-born world traveler with an impressive wine collection. As a result, when my father awoke from the anesthesia, this genteel surgeon in a respectable Hermès necktie was the person who delivered the bad news.

The rarity, aggressiveness, and chemotherapy-resistance of my father's particular type of sarcoma meant that the prognosis for anyone was not promising. With all those cancerous cells swimming around in his body after the rupture, the prognosis for my father was even worse. Given all of these factors, my sisters and I could not understand why anyone would select a general surgeon to manage and direct his care instead of an oncologist with at least some experience treating this sort of cancer. My father didn't seem to concern himself with what was medically sound or logical, though. When he looked at the man in the Hermès tie, he felt he was in good hands, and that was that.

The rarity, aggressiveness, and chemotherapy-resistance of my father's particular type of sarcoma meant that the prognosis for anyone was not promising. With all those cancerous cells swimming around in his body after the rupture, the prognosis for my father was even worse. Given all of these factors, my sisters and I could not understand why anyone would select a general surgeon to manage and direct his care instead of an oncologist with at least some experience treating this sort of cancer. My father didn't seem to concern himself with what was medically sound or logical, though. When he looked at the man in the Hermès tie, he felt he was in good hands, and that was that.

Not long after my father was released from the hospital for the first time and within days of realizing that this rare form of cancer was in all likelihood terminal, he gathered his adult children around him to let us know that if he had to die young, he was "going to go down fighting." He seemed hopeful that through his outward responses and fierce attitude he would refuse to be a "victim" and in so doing accomplish something profound. I think my father truly believed that, in the process of grappling with this disease, he could show his children how to "die with dignity."

My father and I rarely came at things from the same perspective. To my mind, being sick usually sucks; trauma can change you forever; and enduring pain and anguish at times feels unbearable. When I think about those experiences, I have a hard time identifying the champions or the heroes. And if there is virtue or glory to be had, I don't see that, either. While I believe that courage, dignity, and fortitude are admirable traits, I have yet to find any evidence of how those characteristics reliably help people avoid heartache, illness, pain, or death. So when my father made his declaration to all of us, I had no idea what he meant.

I never asked my father how he imagined himself fighting for a dignified death. In my estimation, though, fighting and dignity rarely factored into my father's experiences of living with cancer. What I know for certain is that, with the aid of a general surgeon in understated designer neckties, my father endured multiple surgeries (some needed others probably not) along with several elongated hospital stays, and a period of coma-like unconsciousness followed by months in a decrepit rehabilitation center. After two years of that and with scores of palliative drugs, round-the-clock nursing, tireless attention from his wife, and lots of pain and grief, my father died just short of his 60th birthday. I can't say if he died with dignity or not. But no one won any battles; no medals or trophies were handed out; and in the end my father was not a survivor, but a victim of cancer.

According to several thesauruses, the word "victim" is synonymous with words like wretch, fool, pushover, and sucker. I don't know why victim status has become so shameful or how terms like "patient," "sufferer," or "griever" became so unpalatable, but I am not convinced that we improve things by replacing those words with images of warriors defeating evil enemies or by exchanging supposedly marginalizing language for ideas about "staying strong." The more I think about our society's aversion to labeling someone a victim and our propensity to lionize survivorhood and the valor that ostensibly accompanies it, the more I wonder if we are really seeing people as they are.

My father's choice to seek treatment from an inappropriately qualified doctor seemed irresponsible and irrational in so many ways, and part of me felt angry at the general surgeon who had allowed my father to make such a poor decision. Just before my father died, though, he made a point of admitting that he had been wrong. He knew that we all disapproved of his doctor, but he wasn't regretting his medical care or agreeing with our assessment of the man in the Hermès tie. Rather, he wanted to tell us that there was no good reason for the cancer, no honor in living through pain, and most important of all no "right" way to die.

I can't recall any other time when my father seemed as unguarded with me, and I am grateful for that unadulterated moment of openness from him. I only wish that I had been able to offer him the same compassion and empathy that I easily felt for Carrie when I thought about her unusual coping strategies. My father knew that he was dying and that there was very little he could do to change or control what was inevitable. So, just like Carrie, he simulated control in a way that was true to who he was, regardless of how incomprehensible his decision seemed.

I can't recall any other time when my father seemed as unguarded with me, and I am grateful for that unadulterated moment of openness from him. I only wish that I had been able to offer him the same compassion and empathy that I easily felt for Carrie when I thought about her unusual coping strategies. My father knew that he was dying and that there was very little he could do to change or control what was inevitable. So, just like Carrie, he simulated control in a way that was true to who he was, regardless of how incomprehensible his decision seemed.

All of us cope in arbitrary and irrational ways, and frankly everyone is a survivor until they die. The methods that we use to get by probably do not make us noble, courageous, or dignified; they just make us human. I didn't recognize it at the time, but my father did show me something about how to die, not with dignity or strength or bravery, but with honesty.

This first appeared on The Not Me.

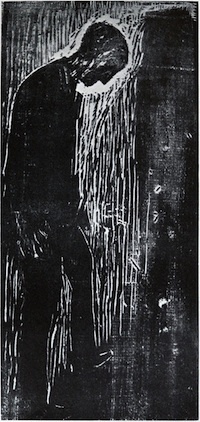

Image credits in order of appearance: Robert Sullivan; Kevin Blake; Caspar David Friedrich; Edvard Munch; Rita Koehler; and Edouard Manet.