Jagat Singh II of Mewar and his Rani celebrating Teej, 1790

Any exhibition on the wealth of a nation's royal class is an exhibition of the inflated amour-propre of men with money and armies at their beck. Well-fed bluebloods wrap themselves in theater curtains, pile on the baubles, and commission royal portraits for which they assume expressions of such preposterous self-importance as to nullify any trace of human dignity. It's a recurring expression, too; you see it in the portraits of Henry VIII, the Florentine dukes of the Renaissance, and Rigaud's portraits of the Sun King. Add to the club the princes on display in the Victoria and Albert's import to the Asian Art Museum, Maharaja: The Splendor of India's Royal Courts.

Seriously. Get over yourself, Bhupinder Singh of Patiala, 1911

It's not that there aren't objects of great beauty or fascination in the Maharaja exhibit, and it's not that you won't learn anything if you're in the market for a (superficial) lesson in Indian history. But it's troubling that this display of ostentation is treated without a hint of irony. Maharajas (from "mahant rajan," or "great king" in Sanskrit) are discussed in noncommittal terms of their duties as rulers -- your usual, "protect, serve and patronize the arts" -- no talk of how they did that.

When considering an exhibition of 300 years of conspicuous consumption on a scale to make Russian gas oligarchs blush, the questions that come to mind are, "Where did all that money come from? What tactics did he use to levy taxes? How did he keep from getting his throat sliced open? Who made these jewels, and what were the conditions in the mines? What was the punishment for speaking out against the maharaja?" Basically, "At what cost, this extravagance?" Nothing.

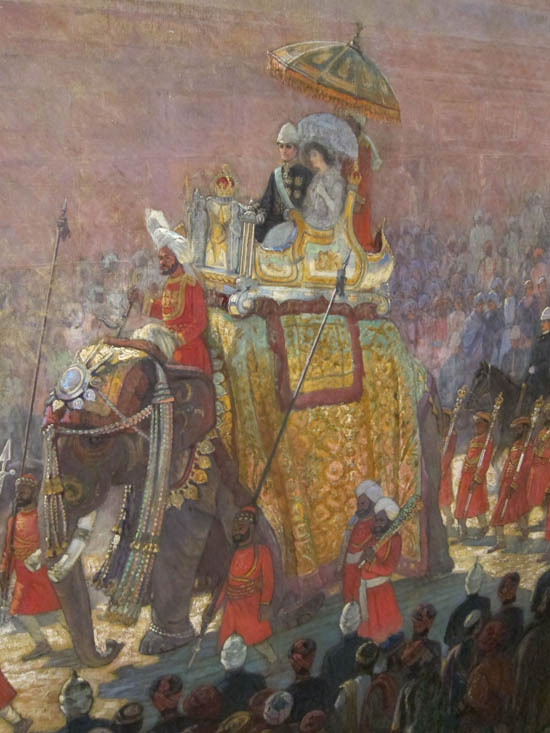

Some of the paintings depict a king atop a magnificently jeweled elephant (the ceremonial elephants are draped with what is called a jhool), and his subjects, in what is described as Darshan, the "dynamic exchange of seeing and being seen by a superior being." In the magnificence of their humility, the kings borrowed this notion from a Hindu one that says a deity, in revealing himself, bestows grace upon his followers, who in turn are made receptive to this grace by seeing him. Darshan is discussed and presented as if there is no possibility that the modern democratic mind could reel at such ridiculousness. Whatever a demigod is, it is not a simple or indisputable concept. Just because the art of the time conveyed an uncomplicated acceptance of the notion that there were superior, even god-like beings who could, by the luck of their birth, bless the less fortunate masses, that does not mean that a retrospective on that art must assume the same. Was there any objection among the people to the ruler taking on the accoutrements of a god? How did the religious hierarchy respond? Was there any discussion, any argument at all in Indian culture around the idea of superior and inferior beings?

There is a little discussion of women, how most rulers were unsurprisingly polygamous and the wives were often great patrons of the arts and religion. One wishes they factored more significantly in the artwork shown here. There is only one erotic painting displayed, which is surprising, as India is known for its erotic art, which was an area of royal patronage. Nor is the subjugation to Great Britain given anything but terse summary of the failed revolts and reluctant concessions that brought India under British control. The matter-of-fact relaying of the rise and fall of the Raj (the British rule) recalls the grade-school history textbooks that gave the barest outline of historical events but withheld the extremes of human experience that were the fallout of those events, to be revealed to us when we were older and could better handle the ugly truth. One gets a greater sense of the tension between the cultures, and their affinities, in a single episode of Jewel in the Crown.

"The Delhi Durbar of 1903" by Roderick McKenzie, 1907, Kolkata

Particularly fascinating are examples of the maharajas' willing adoption of western fashions and lifestyles, most noticeable in the final decades of the Raj. Maharajas were often educated in Europe or by English tutors, and they took up English hobbies such as cricket and fox-hunting. But as India's discontent was coalescing into a viable liberation movement under the leadership of Mohandas Gandhi, the maharajas appeared more flamboyantly europhilic than ever. Several drawings depict the Art Deco interior of the Umaid Bhawan palace in Jodphur, commissioned by Maharaja Umaid Singh and designed by British architect Henry Lancaster. Dazzling, to be sure, but dissonant with the burgeoning Indian pride movement gaining traction outside the palace grounds. One is left to guess at the consequence, if any, of this disparity between the rulers' championing of the culture of the oppressors, and the people's struggle to shrug it off. Other examples of the Indian princes looking westward for their luxuries include a spectacular 1,000-carat diamond and ruby Cartier necklace (although many of the stones have been replaced with cubic zirconia after the originals were lost or sold off) commissioned by Maharaja Bhupinder Singh of Patiala, and several stunning saris made in the traditional style by Parisian couture houses. Even the humblest sari can hold its own as a thing of beauty against the fanciest western dress of any era, yet the museum offers no insight into why privileged Indian women preferred to have French-made versions of their native dress, so one is left to assume it was the usual fondness for the dominant culture on the part of a nation with an inferiority complex, like the 19th-century French-speaking Russian aristocrats who spoke Russian only with their servants.

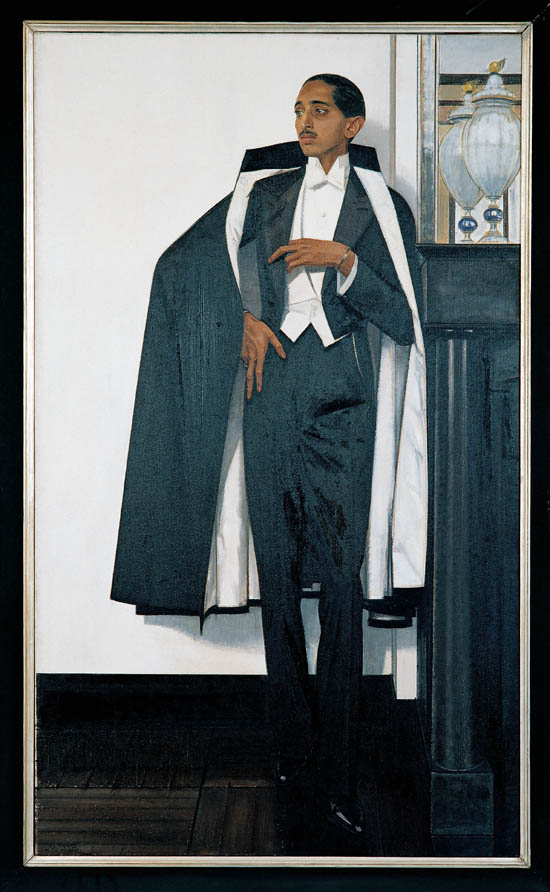

Not only does this conflict with the celebratory spirit of the installation (and failing to acknowledge that one could wonder at this complexity indicates that even the curators don't take issue with it), it seems it would have conflicted with the patriotic movement that was strengthening during these same years. Some went farther: Rashwant Rao Holkar II, ruler of Indor, posed in Western evening dress for this portrait by Bernard Boutet de Monvel, in 1929.

This, an array of furniture from his Modernist Manik Bagh Palace (by a German architect), and several sensational portraits of the ruler and his wife by Man Ray show a man fully given over to western style and sensibility. What did it mean, that while the populist movement pursued political and cultural self-reclamation, the rulers of the nation donned full dandy get-up and went on blinkered shopping trips for the white man's trinkets? The exhibit ignores this question.

Of course you should see this show. The work is beautiful, sometimes breath-taking. But it seems to have been arranged and presented without acknowledging that displays of great wealth (especially out of notoriously impoverished countries) raise uncomfortable questions. One shouldn't leave the museum suspecting that the beauty one enjoyed was some sort of decoy, rather than the catalyst of revelation.

At Istanbul's Topkapi Palace, I saw an old photograph of a gorgeously adorned camel. The adjacent description stated that when these camels grew too old to carry their royal human cargo, their legs were sliced off at the knees while still standing. Of course this bit of savagery is appalling, but one must respect the Turkish people (or the people in charge of curating and presenting their history) for not avoiding or veiling over the more grim aspects of their empire's modus operandi. There, in that glittering monument to the magnificence of Istanbul, they were not afraid to reveal its foulness as well. That is what is missing from The Splendors of the Indian Royal Courts -- the risk of truth-telling, the trust that the story you tell is strengthened, not diminished, by telling the other side.

This article originally appeared on SF Weekly's blog, The Exhibitionist.