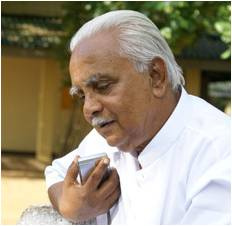

At a farewell gathering for a long-time employee, Ahangamage Tudor Ariyaratne, founder of the Sarvodaya Shramadana Movement, approaches the podium dressed in his trademark white sarong, knee-length shirt and sandals. Speaking in both Sinhala and English, Ariyaratne first apologizes for rarely praising his employees.

"The greatest enemy that each one of us has is our ego," Ariyaratne explains to an audience of more than 100 district representatives and executives.

In the front row of the circular conference room, the outgoing Deputy Executive Director of Technological Programs, Udani Mendis, wipes her tears as she listens to Ariyaratne finally praise her work, after 10 years of service.

"He was not a boss," Mendis says. "He was like a father to all of us."

The meek 77-year-old Ariyaratne, often called the "Gandhi of Sri Lanka," has become popular for his massive meditation sessions in which hundreds of thousands of people converge to pray for peace. His Sarvodaya Shramadana Movement, which Ariyaratne established 51 years ago, is based on Buddhist and Gandhian principles -- Sarvodaya in Sanskrit means "awakening of all" and Shramadana "to donate effort." The organization is the largest civil society movement in the country. By its own estimations, it works in 15,000 villages and attracts nearly a million volunteers annually. Some scholars have described its network of organizations with 3000 paid employees as the world's largest peoples' participatory development movement.

Those that know Ari, as he is affectionately called by intimates, describe a man with a deep belief in the Buddhist faith on which he was weaned.

"The winning combination for Ari is the sense of connectedness to everyone that is implicit in Buddhist values and connecting that with a very strong commitment to nonviolence," says Marc Gopin, professor of conflict resolution at George Mason University in Washington D.C., who has known Ariyaratne for decades.

Ariyaratne, the third of six children, was born in the coastal town of Unawatuna to middle-class parents. His father was a businessman, and religion was a key to the family.

"My parents were devout Buddhists," says Ariyaratne. "Our ancestral home was situated adjoining the village temple. From childhood, I was educated and influenced by very learned and revered monks in the temple. I was inspired by the social aspect of Buddha's teachings, which I thought I could experiment with."

The Buddhist influence is evident in the way he runs the organization. The farewell meeting ends with a Buddhist prayer, and Buddha statues adorn offices. Employees fall at his feet to worship him -- a traditional mark of respect for elders in many South Asian countries.

"I see Mr. Ariyaratne as a person who showed society and the world the Buddhist Dharma [teachings] in a practical manner," says Uduwe Dhammaloka Thera, a Buddhist priest and (independent) Member of Parliament.

The Buddhist principles that Ariyaratne used to form his movement was different from the mainstream Buddhism that emerged in post-colonial years. After independence in 1948, religion became an inseparable part of the national identity of the Sinhala-Buddhist majority ethnic group that had been subjected to discrimination by British colonialists who had undermined Buddhism, calling it ill-suited for modern society.

George Bond, professor of religion at Northwestern University who knows Ariyaratne well and wrote about the movement in "Buddhism at Work," describes Ariyaratne's Buddhist philosophy as "socially engaged Buddhism."

"Believing that Buddhist principles should be applied to social problems, Sarvodaya articulated a vision of a new social order founded on Buddhist values but inclusive of all people," Bond writes in his book.

Despite Sarvodaya's all-encompassing approach, its roots in Buddhism have presented limitations.

Jehan Perera, the executive director of the National Peace Council of Sri Lanka, who worked at Sarvodaya for eight years, says Sarvodaya's impact is stronger in the country's Sinhala-Buddhist regions than in the Tamil and Muslim areas.

"However, his interpretation of Buddhism is not an aggressive Buddhism," Perera says. "Therefore, he has been able to, more successfully than any other NGO, mobilize large numbers of people, both Buddhist and religious minorities to come together."

During Sri Lanka's nearly 30-year-long war between the government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, Ariyaratne consistently stood out as a charismatic exception, condemning war and encouraging peace through dialogue.

"Ariyaratne is regarded as a credible spokesman for peace and someone people can look up to," says Bond.

Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu, executive director of the Center for Policy Alternatives and one of Sri Lanka's prominent Tamil intellectuals says Ariyaratne's organization is known for bringing people together. Saravanamuttu says Ariyaratne's approach and his experience could be significant in cultivating the future generation of leaders.

"He has a large following, and Sarvodaya works in all parts of the country and is known to promote ethnic harmony between the communities," says Saravanamuttu.

Ariyaratne, who is a graduate of Sri Jayawardenapura University, also drew inspiration from pacific leaders in neighboring India. In addition to Mahatma Gandhi's nonviolent philosophy, Indian social reformer Acharya Vinoba Bhave's land gift movement, in which land owners were encourage to donate land to their poorer neighbors, also influenced Ariyaratne's work.

For this father of six and grandfather of ten, the movement is his life's work and has now become a family affair. His home, tucked away in the town of Moratuwa not too far from the capital Colombo, is a part of the Sarvodaya headquarters, a vast complex occupying an entire street. His son, Vinya, a medical doctor, gave up being a professor to become the organization's executive director. His wife, Neetha, is in charge of the Sarvodaya entity that works with children and the elderly. And his daughter, Charika Marasinghe, oversees the organization's peace and meditation center.

Ariyaratne's work has earned him numerous international accolades, honorary doctorates and a nomination in 2005 for the Nobel Peace Prize. The massive peaceful gatherings, emblematic of Sarvodaya's expansive network and Ariyaratne's magnetic personality, have also turned this soft-spoken man of small stature into a hot commodity for many politicians who have unsuccessfully lobbied for his support.

"I always believed that man had a higher purpose in life, a spiritual purpose, which is quite the opposite of going after power, money or publicity," Ariyaratne says.

But his work has also attracted negative publicity. Some detractors believe Ariyaratne wrongfully took credit for pioneering the "shramadana movement" in Sri Lanka though he is generally credited with its rapid expansion.

Perhaps Ariyaratne's harshest critic is Susantha Goonatilake, a former president of the Sri Lanka Association for the Advancement of Science, who has written about Ariyaratne and Sarvodaya. Goonatilake accuses Ariyaratne of "gross wrongdoing" and calls his image "a façade."

"His philosophy has changed continuously depending on the donor," Dr. Goonatilake asserts. "There is no consistent philosophy."

The criticism, in part, stems from the ongoing controversy surrounding Sri Lanka's nonprofit sector, which has been criticized for exploiting the country for financial gain. But despite the controversies, few deny Ariyaratne's impact.

"It's not enough just to deliver speeches about creating harmony between the ethnic communities," says Dhammaloka Thera. "Communities have to come together by taking part in activities, and Mr. Ariyaratne implements that."

Photos courtesy Sarvodaya Media Unit