Autumn is the season for remembrance, and nobody does remembrance like the Parisians. Crisp air, sunny skies, fewer tourists (at least most places) and easy public bike rentals: what could be a better moment to leap into the sentiments of moments past: the graphic intensity of mid-century Mexican painters and sculptors, the revisited brilliance of Oscar Wilde who died in Paris a victim of British sexual duplicity, and the always charming--if occasionally vapid--surrealist advertising images of semi-surrealist René Magritte.

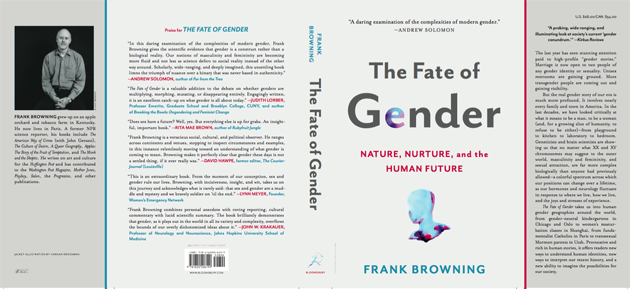

Why not start with Magritte at the Pompidou Museum and one of his most famous images, Ceci N'est Pas Une Pomme, or This Is Not An Apple, a complement to his more famous photographic illustration of a pipe called This Is Not A Pipe.

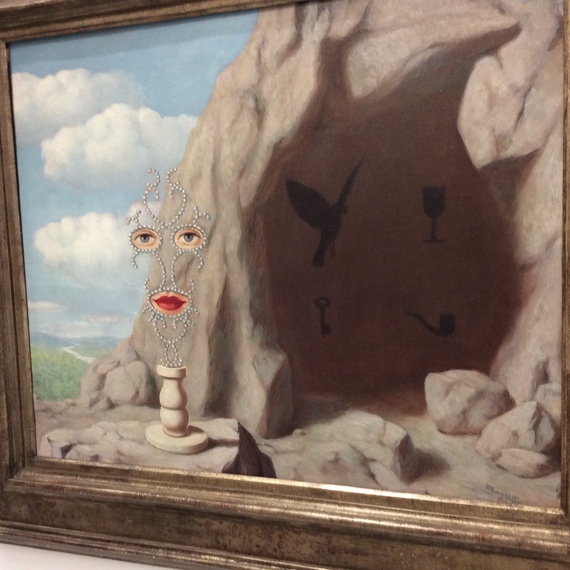

Magritte, who made his way mostly as an advertising illustrator, persistently argued that his dodgy images of people and objects displaced from ordinary reality were drawn from and inspired by Plato's elemental Allegory of the Cave in which several humans are chained to the wall of a cave and begin to describe the nature of external reality through how they perceive the shadows of actual beings cast upon the walls. Perception is nothing more than the reality we imagine through the limited neurology given our eyes and brains.

Magritte was not particularly original: Plato explained the notion two and a half millennia ago, but as a technical master of perceptual delusion (the title of the show is The Treachery of Images), occasionally inspired by reported "realities" of the day, he well captured the post-psychoanalytic anxieties of a 20th century, which in the face of holocaust, had lost its faith in "reality." Dead now for nearly half a century, Magritte never fails to draw huge crowds into his perceptual cave, and this show at the Centre Pompidou is no exception.

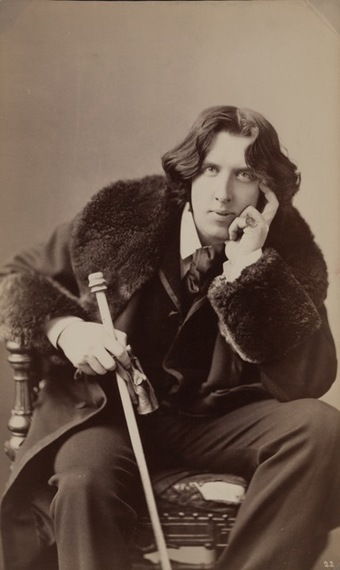

Vastly more interesting in the realm of remembrance is the appreciation of Oscar Wilde, L'Impertenant Absolu (Absolute Impertenant) at the Petit Palais.

--© Library of Congress, Washington

Wilde of course was the master of the dazzling aphorism. The one that opens the exhibit is a sublime periscope onto the tragedy of Wilde's life: "A good reputation? It is one of the many annoyances to which I have been subjected."

--Guido Reni, St. Sebastian © Musei di Srada Nuova

Arguably one of the most brilliant thinkers and writers in the English language, Wilde was steeped in classical literature at Trinity College Dublin and at Oxford. First an art critic championing the new "Aesthetic Movement" paintings of classical figures, including Remi's provocative portrayal of St. Sebastain, he quickly became a companion and frequenter of the leading post-impressionist artists in Britain, the US and Europe, a leading playwright for the London stage and a largely forgotten poet of the insults of crude 19th century capitalism on the desperate poor.

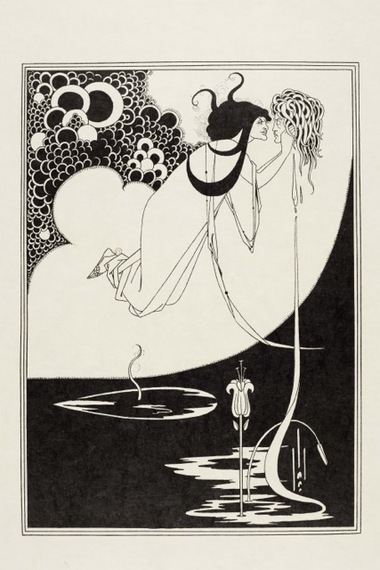

The exhibit includes many of his letters, first editions of his books, a video interview with his grandson, clips from the Al Pacino version of his operetta Salomé, the Biblical femme fatale who demanded the head of John the Baptist--and some of the rarely seen ink drawings of Aubrey Beardsley, which like some of Wilde's erotic writing were long banned in Britain.

A self-described dandy, Wilde was a hit on his national lecture tour of the United States, earning him enough to spend several months in Paris and the South of France, during which he wrote Salomé in flawless French. A darling of the champagne classes despite his firm socialist values, he drew even more fame from two stage masterworks, The Importance of Being Earnest and Lady Windemere's Fan. The plays are at once a romp with the elite and a not always well acknowledged dissection of the vacuity of their pretensions, or as he wrote of one of his more prescient aphorisms,

"It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances. The true mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible."

Always keenly aware of the contradictions in both his life and work, Wilde could not resist being drawn closer and closer to the flame of his own destruction--not least in his hardly discreet love affair with the young aristocrat and translator, Lord Alfred Douglass. Nothing in the Petit Palais exhibit is more moving than Wilde's passionate and explicit love letter of to the beautiful, boyish "Bosey" Douglas, which was eventually used by an unremembered London prosecutor to condemn Wilde to two years hard labor in Redding Gaol.

Wilde could have fled to and found refuge in France, but instead he chose to stand trial and confront the hypocrisies of the Crown court. When he was freed two years later, broke and in failing health, he did leave England for France where he finished his greatest poem, The Ballade of Redding Gaol, sending what little money he could afford to his prisoners he had known in prison.

Across the street from Le Petit Palais, Le Grand Palais has opened a three-month long exhibition of paintings, sculptures and films tracing the heart-stopping record of Mexico's greatest 20th Century artists. "Mexico stands apart as a nation that understands its museums as integral to expressing the soul of its peoples and its cultures, at once a sophisticated panorama of its history and an expression of their rich diversity," independent international museum curator Vanda Vitalli explained to me. Vitalli had no personal role in the current exhibition, but she was hardly surprised by the scope and intensity of these pieces on display until mid-January.

The show is relatively chronological from the triumph of its revolutionary independence from Spain in 1920 up through the 1950s. It opens with the early appetite of Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco and others of their era for contemporary European art movements; then the exhibit carefully tracks their return to Mexico and their reintegration into the vital landscapes and human figures of indigenous Mexico--a path parallel today's art in contemporary China.

Throwing off the bitter, brutal yoke the dictator-identified Catholic Church is a persistent concern throughout the growth and flowering of Mexican art, and it is everywhere in this show, from Orozco's "Christ destroying his cross to the clip from Sergei Eisenstein's Vive Mexique! Where a smug priest offers sprinkles of holy water to a mass of starving peasants. Unlike the rapidly individualist American Revolution, which only advanced the slaughter of North America's native people, the core of Mexico's liberation struggle was its indigenous population. It's a story in the joy and weeping of Diego Rivera's panoramic, Utopian murals and his sublime peasant girls selling lillies, in Frieda Kahlo's mystical portraits, in Rufino Tamayo's howling, copulating wolf dogs, in Sigueiros invincible--and yet oddly androgynous--self portrait as a revolutionary colonel.

Unlike the clever and often banal ironies that brought fame to the adman Magritte, these works weep and roar with passion. They are remembrances of tragedies that cannot be forgotten even as they sing with joy at the prospect--not yet realized--of the only North American utopian dream not founded on collective genocide.

--