As baseball inducts slugger Andre Dawson, umpire Doug Harvey and manager Whitey Herzog into its Hall of Fame at ceremonies in Cooperstown, New York on Sunday, the glaring absence of Marvin Miller, the first executive director of the players' union, and Curt Flood, the baseball pioneer who challenged the sport's feudal system, reminds us of the narrow parochialism and conservatism of baseball's current establishment.

All histories of baseball point with pride to its role in helping to dismantle America's racial caste system when Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947. In recent years, however, Major League Baseball (MLB) has hardly distinguished itself as a paragon of American virtue or a pioneer for social justice or moral clarity. Its corporate mentality, its failure to deal with widespread drug use, and its decline in popularity among America's youth (more of whom now play soccer than Little League baseball), don't reflect well on what its pooh-bahs still call the "national pastime."

Here are five things that baseball could do to redeem itself to reflect the best of America's liberty-and-justice-for-all values.

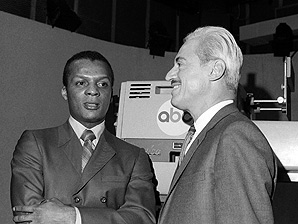

1. Elect Marvin Miller to the Hall of Fame

The man who freed ballplayers from indentured servitude has been kept out of the Hall of Fame as a result of a coup engineered by the conservative cabal that controls Major League Baseball.

Baseball owes a huge debt of gratitude to Miller, who, as director of the players union from 1966 to 1983, dramatically improved players' pay and working conditions, as Kelly Candaele and I explained in an article in The Nation two years ago. At the time, we urged the union and players -- Hall of Famers, veterans and current players alike -- to speak out on behalf of this baseball and labor pioneer, then 91, before it's too late. Miller is still alive, but whether his chances to enter the Hall of Fame are also alive depends on whether fans and players demand it.

Miller has been snubbed four times by the Hall of Fame. In 2007, he received 63 percent, 12 percent short of the magic number. He was the only candidate to earn a majority of the votes. That tally for Miller was obviously too close for comfort for baseball's establishment, concerned that he would probably reach the three-quarters threshold in the next vote. Later that year, the Hall of Fame board carried out a coup. They changed the rules and transformed a democratic voting process into a conspiracy of cronies. They created a twelve-member committee, responsible solely for considering baseball executives, with nine votes required for selection. The much smaller group included seven former executives, two Hall of Fame players, and three writers. When that group met in December, Miller only got three votes.

Before Miller, team owners ruled baseball with no pretense of giving players the same rights enjoyed by workers in other industries. Players were tethered to their teams through the reserve clause in every player's contract. Under the reserve clause, contracts were limited to one season. The contract "reserved" the team's right to "retain" the player for the next season. Other teams were not permitted to bid for the player and players were not permitted to negotiate with other teams. Teams offered players their contracts on a take-it-or-leave-it basis. Players had no insurance, no real pensions, and awful medical treatment.

With Miller's guidance, the players association negotiated the first collective bargaining agreement in 1968, which established players' rights to binding arbitration over salaries and grievances. Players also won the right to have agents to negotiate their contracts. In 1976, they gained the right to become free agents, allowing players to decide for themselves which employer they wanted to work for, to veto proposed trades and to bargain for the best contract. Under Miller, the union won increased per-diem allowances, improvements in travel conditions, better training facilities, locker room conditions and medical treatment.

In 1967, the minimum salary was $6,000 and the average salary was $19,000. The first collective bargaining agreement the next year raised the minimum to $10,000--paltry by today's standards, but a giant improvement in players' standard of living back then. When Miller retired in 1982, the average player salary had increased to $240,000. Today, the minimum salary is $400,000 and the average salary is over $2.9 million. Today, unlike many ex-National Football League players who scrape by because of a much weaker union, even baseball players who had short and less-than-illustrious careers have good retirement benefits.

In 1992, Red Barber, the great Hall of Fame broadcaster for the Dodgers and Yankees, said, "Marvin Miller, along with Babe Ruth and Jackie Robinson, is one of the two or three most important men in baseball history."

Since New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner died last week, some sportswriters and even some players have been pushing to get him into the Hall. Whether Steinbrenner's misdeeds as a convicted criminal compare with Pete Rose's gambling activities, which have kept him out of the Hall, is a matter of opinion. But no serious baseball fan can argue that Steinbrenner played a larger role than Miller in changing the game.

Unfortunately, it is unlikely that a majority of current players even know who Marvin Miller is, or how much they owe this legendary baseball pioneer. The MLBPA should educate its members about Miller and lead a movement to get him into the Hall of Fame while he's still alive.

Many high-profile Hall of Fame players - including Tom Seaver, Hank Aaron, Nolan Ryan, and Reggie Jackson - have spoken out against Miller's exclusion from the Hall of Fame. But the MLBPA needs to organize a campaign, led by these and other Hall of Famers - on Miller's behalf. The Player's Association should circulate a petition of both veterans and current players demanding that Miller be selected. They should lobby the players and writers on the selection committee to demand that the no other management executives be selected to the Hall of Fame until Miller is voted in.

2. Elect Curt Flood to the Hall of Fame

Curt Flood's exclusion from the Hall of Fame is another outrageous injustice. It would be entirely fitting for Flood and Miller to enter the Hall at the same time. Both played key roles in upending baseball's feudal system.

This year is the 40th anniversary of Flood's challenge to baseball's s reserve clause, which reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 1970. The Court ruled against Flood, but he paved the way. Within five years, the reserve clause had been abolished and players became free agents, paid according to their abilities and their value to their teams.

Flood was only 31 when he stood up to baseball's establishment. He was in his prime -- an outstanding hitter, runner, and centerfielder with Hall of Fame statistics.

He played in 1759 games, had a .293 lifetime average, won seven Gold Gloves, and was a three-time All Star (1964, 1966, and1968). Flood hit over .300 six times during a 15-year major league career that began in 1956. He had 1,861 hits, but had he been able to remain in baseball, he probably would have reached the magic number of 3,000 hits. He played on the St. Louis Cardinals teams that won the World Series Championships in 1964 and 1967.

Flood played for the Cardinals for 12 seasons. After the 1969 season, the Cardinals tried to trade the 31-year old Flood to the Philadelphia Phillies. Under the reserve clause, part of the standard player's contract, players could be traded without having any say in the matter. But Flood didn't want to move to Philadelphia, which he called "the nation's northernmost southern city." More importantly, he objected to being treated like a piece of property and to the reserve clause's restriction on his freedom. Flood considered himself a "well-paid slave."

In a letter to Commissioner Bowie Kuhn. Flood wrote:

"After 12 years in the major leagues, I do not feel I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes. I believe that any system which produces that result violates my basic rights as a citizen and is inconsistent with the laws of the United States and of the sovereign States."

With the backing the MLBPA and Miller (who recruited former U.S. Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg, whom Miller knew when they both worked for the steelworkers' union, to be Flood's lawyer), Flood became the plaintiff in the case known as Flood v. Kuhn (Commissioner Bowie Kuhn), which began in January 1970. In June 1972, the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled against Flood by a 5-3 vote and upheld baseball's absurd exemption from federal antitrust statutes.

But Flood had set in motion a movement for change. As the New York Times' William Rhoden wrote this week:

"In 1975, after an arbitrator freed Catfish Hunter from his contract with the A's, Hunter had a five-year, $3.35 million contract with the Yankees. It was the highest player salary in baseball at the time. More significantly, the transaction illuminated the potential of free agency for top-notch players and teams that could afford them. All this because Flood stood up and said, enough. Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally won their free-agency suit in 1976, but it was Flood who had started the fight. He deserves a bust in the Hall of Fame and a statue outside every major league stadium."

Flood paid a huge financial and emotion price for his course. His 1970 salary would have been $100,000, but he was no longer employable - blacklisted by the owners - despite his talent. Instead, he spent years traveling to Europe, devoting himself to painting and writing, including his autobiography, The Way It Is.

Looking back, Flood explained,

"I guess you really have to understand who that person, who that Curt Flood was. I'm a child of the sixties, I'm a man of the sixties. During that period of time this country was coming apart at the seams. We were in Southeast Asia. Good men were dying for America and for the Constitution. In the southern part of the United States we were marching for civil rights and Dr. King had been assassinated, and we lost the Kennedys. And to think that merely because I was a professional baseball player, I could ignore what was going on outside the walls of Busch Stadium was truly hypocrisy and now I found that all of those rights that these great Americans were dying for, I didn't have in my own profession."

Flood belongs in the Hall of Fame because of his exploits on the field and his battle against exploitation off the field. He was a true baseball pioneer. Just as Jackie Robinson broke baseball's color barrier, Flood helped break the sport's economic caste system.

In 1999, Time named Flood (who died in 1997 at age 59) one of the 10 most influential people in sports in the 20th century.

A 35-year old Los Angeles baseball fan, Daniel Grindlinger, created a Facebook page, "Put Curt Flood In The Hall Of Fame." Flood's family supports the campaign to get him into the Hall.

Upon Flood's untimely death, Miller said, "At the time Curt Flood decided to challenge baseball's reserve clause, he was perhaps the sport's premier center fielder. And yet he chose to fight an injustice, knowing that even if by some miracle he won, his career as a professional player would be over. At no time did he waver in his commitment and determination. He had experienced something that was inherently unfair and was determined to right the wrong, not so much for himself, but for those who would come after him. Few praised him for this, then or now. There is no Hall of Fame for people like Curt."

But there should be.

3. End Baseball's Sweatshop Abuses

Thanks to Miller and Flood, Major League baseball was forced to change and recognize players' rights as employees, which meant, among other things, giving players more equitable share of teams' corporate profits.

When Miller led the MLBPA, he sought to raise players' political awareness. "We didn't just explain the labor laws," he recalled in an interview. "We had to get players to understand that they were a union. We did a lot of internal education to talk to players about broader issues."

Unfortunately, those days are long gone. Having freed the players from the owners' domination, the union now focuses on negotiating to give players a greater share of proceeds from ticket sales, television contracts and the marketing of player names and team logos.

Now the MLBPA is the nation's strongest union, but a large part of baseball's workforce still labors under sweatshop conditions. The MLBPA should not only lead a crusade to get Miller and Flood into the Hall of Fame, but also initiate a campaign to rid baseball of its ties to sweatshops.

Major league baseball's uniforms are made by union workers in a factory owned by the VF Corporation, but the baseballs are produced in a Central American sweatshop.

In 2004, the New York Times, drawing on a report by National Labor Committee called Foul Ball, shed light on the terrible working conditions at the Rawlings baseball factory in the remote city of Turrialba, Costa Rica. The story revealed that the Costa Rican workers who stitch baseballs for the major leagues were paid 30 cents for each ball, which were then sold for $15 in US sporting-goods stores. According to a local doctor, a third of the workers developed carpal tunnel syndrome, an often-debilitating pain and numbness of the hands and wrists.

According to observers, the workers who sew the baseballs must complete one ball every 15 minutes. The factory lacks air conditioning and temperatures exceed 100 degrees. Workers are required to ask permission to use bathrooms. The company prohibits workers from speaking to each other on the factory floor. Employees work an average of 11 -12 hours per day. They must be available to work on Saturdays or risk being fired. Not surprisingly, workers fear being overheard talking about organizing a union. Today, about 600 workers produce over 2.4 million baseballs in the factory each year. Most of them are purchased by Major League Baseball, but the minor leagues and the NCAA college World Series use them as well. The factory is located in a Free Trade Zone, which means it is exempt from corporate taxes

A recent puff-piece about the factory in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram -- for which the reporter apparently interviewed Rawlings executives but no workers -- observed:

The plant, in a free-trade zone where tariffs are reduced, brings in about $21 million for Costa Rica annually. It appears Costa Rica is happy to be the source of the most vital element of America's Pastime.

The MLBPA has been silent about the sweatshop conditions under which their baseballs are made. The players union could draw attention to the problem by sending a fact-finding delegation of players to inspect the working conditions at the Costa Rican sweatshop, now owned by Jarden Corporation, Rawlings' parent firm.

In addition, most of the merchandise sold at baseball stadiums - such as the hats, shirts, and bobble-head dolls - are produced in sweatshops in China, Central America, Bangladesh and Indonesia. MLB negotiates the contracts for these items and the players and teams share the revenues from the sale of these products.

The players association could also demand that teams provide a living wage for all stadium employees and encourage politically conscious athletes to express their views and even walk picket lines and do commercials for labor causes.

4. Move Next Year's All-Star Game Out of Arizona

Major league baseball players and baseball fans should boycott the 2011 All-Star game, which is scheduled to take place in Phoenix, until Arizona's unfair immigration law is repealed or the game is moved to an another location. The law promotes racial profiling by requiring police to question anyone who appears to be in the country illegally. Players and fans should pressure Commissioner Bud Selig to move the game.

Baseball has long been a game populated by immigrants. Since the late 1800s, the ranks of professional players has reflected the nation's changing demographics (with the exception of the exclusion of African Americans until 1947). Both on and off the field, baseball has been one way for immigrants - Germans, Irish, Jews, Poles, Italians, and now Latinos -- to become more "Americanized." Joe DiMaggio and Hank Greenberg were great sources of pride for Italian and Jewish immigrants and their children.

As Robert Elias observes in his fascinating new book, The Empire Strikes Out, American business, political, and military leaders have long encouraged the export of baseball to other countries as a way to promote U.S. economic and military might and culture. The large and growing number of Latino and Asian ballplayers in MLB is a legacy of those efforts.

Latinos now represent 27 percent of all major league players and 28 percent of players are foreign born. As Senator Robert Melendez of New Jersey wrote in a letter to MLBPA executive director Michael Weiner:

"These players come to the United States legally and should not be subjected to the humiliation and harassment that SB1070 would inflict. Imagine if your players and their families were subjected to interrogation by law enforcement, simply because they look a certain way. Imagine if M.L.B. fans - many of whom are Hispanic - were subjected to that same type of interrogation if they were to attend the All-Star Game. That would truly be an embarrassment and an injustice, not only to M.L.B., but to the values and ideals we hold as Americans."

The controversy around the Phoenix game heated up this summer and many players -- who are typically cautious about getting involved in political and social controversies -- spoke up.

Ozzie Guillen, the Chicago White Sox manager who comes from Venezuela, said that he would boycott the 2011 All Star game "as a Latin American" if it were held in Phoenix.

Discussing the Arizona law, St. Louis Cardinals All-Star slugger Albert Pujols told USA Today: "I'm opposed to it. How are you going to tell me that, me being Hispanic, if you stop me and I don't have my ID, you're going to arrest me? That can't be."

Jose Valverde, the Detroit Tigers relief pitcher, told the Arizona Republic that the law is "the stupidest thing you can ever have." Yovani Gallardo, the Milwaukee Brewers All-Star pitcher, said: "If the game is in Arizona, I will totally boycott."

Jerry Hairston of the San Diego Padres told ESPN: "It reminds me of seeing the old movies with the Nazis when they ask you to show your papers. It's not right. I can't imagine my mom -- who's been a U.S. citizen longer than I've been alive, who was born and raised in Mexico -- being asked to show her papers. I can't imagine that happening. So it kind of hits home for me."

Padres first baseman Adrian Gonzalez, who holds dual citizenship in the United States and Mexico, told the San Diego Union-Tribune, "It's immoral. They're violating human rights. In a way, it goes against what this country was built on. This is discrimination. Are they going to pass out a picture saying 'You should look like this and you're fine, but if you don't, do people have the right to question you?' That's profiling."

Heath Bell, another Padre, said: "If I'm voted [into the All-Star team] I'm going to have to really think about [playing], because I have a lot of friends that are not white. Sometimes you need to stick up for your friends and family."

MLBPA's Weiner issued a statement opposing the Arizona law, although he stopped short of recommending a boycott. He said that the impact of the Arizona bill:

"is not limited to the players on one team. The international players on the [Arizona] Diamondbacks work and, with their families, reside in Arizona from April through September or October. In addition, during the season, hundreds of international players on opposing major league teams travel to Arizona to play the Diamondbacks. And, the spring training homes of half of the 30 major league teams are now in Arizona. All of these players, as well as their families, could be adversely affected, even though their presence in the United States is legal. Each of them must be ready to prove, at any time, his identity and the legality of his being in Arizona to any state or local official with suspicion of his immigration status. This law also may affect players who are US citizens but are suspected by law enforcement of being of foreign descent. The Major League Baseball Players Association opposes this law as written. We hope that the law is repealed or modified promptly. If the current law goes into effect, the MLBPA will consider additional steps necessary to protect the rights and interests of our members."

The players union needs to take the next step and authorize a player boycott of the Phoenix All-Star game. If the game were cancelled, this would be a significant sacrifice -- or statement of principle -- by the players, since the proceeds from the All Star game go to their pension fund. But if Commissioner Selig believes that the MLBPA would actually carry out a boycott -- and if a significant proportion of fans support the players -- then it is likely that he would move the game to another city. (Unless, of course, the Arizona legislature repeals the outrageous law).

5. Open the Closet

Jackie Robinson broke baseball's color line. Marvin Miller and Curt Flood helped baseball eliminate the last vestiges of economic feudalism. Who will bring baseball out of the closet? In other words, is baseball ready to have an openly gay player?

Out-of-the closet gays and lesbians have been elected to political office at every level, including Congress. They are visible and prominent in the entertainment industry, business, journalism, and the clergy. Many big cities and suburbs have openly gay schoolteachers. TV sit-coms have openly gay characters. A few years ago, New York Times began to include same-sex wedding announcements. Polls show that Americans are increasingly supportive of gay marriage. The U.S. military will soon overturn its "don't ask, don't tell" rule.

Certain spheres of American life, however, have resisted change. Professional sports leagues may not enforce a "don't ask, don't tell" policy overtly, but in practice its force is equally felt, especially for male athletes.

It is easier for athletes in individual sports -- like tennis star Martina Navratilova and diver Greg Louganis -- to come out of the closet than players on team sports. This is confirmed by the list of "out" athletes available on the OutSports website.

According to conventional wisdom, a gay teammate would threaten the macho camaraderie that involves constant butt-slapping and the close physical proximity of the locker room. So while there are no doubt homosexuals currently playing in the National Football League, National Basketball Association, and Major League Baseball, they are deep in the closet.

Some players have come out after they retired. These include NFL players David Kopay, Roy Simmons, and Esera Tuaolo and NBA player John Amaechi. Only two gay former major league baseball players, Glenn Burke and Billy Bean, have come out of the closet. Burke, who played for the Dodgers and Oakland A's from 1976 to 1979, came out to family and friends in 1975 but lived in fear that his teammates and managers would discover his sexual orientation, as he explained in his autobiography, Out at Home, published posthumously. Frustrated, Burke retired and kept his homosexuality secret until he cooperated for a 1982 article in Inside Sports magazine. Burke continued to play competitive sports. He won medals in the 100- and 200-meter sprints in the 1982 Gay Games and played basketball in the 1986 Gay Games. Later, Burke struggled with drug abuse, homelessness, and AIDS, from which he eventually died in 1995.

While Bean played for the Tigers, Dodgers, and Padres from 1987 to 1995, he pretended to date women, furtively went to gay bars, and hid his gay lover from teammates and fans. In his published memoir, Going the Other Way, Bean recounts how Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda constantly made homophobic jokes, even as Lasorda's gay son was dying from AIDS. Bean quit when he could no longer stand living a double life. When he came out publicly in 1999, his story made front-page news in the New York Times. In his autobiography, Behind the Mask, Dave Pallone--a major league umpire who was quietly fired in 1988 after rumors about his sexual orientation circulated in the baseball world--contends that there are enough gay major league players to create an All Star team.

A few years ago, Details magazine quoted Bobby Valentine, then manager of the New York Mets, saying that professional baseball is "probably ready for an openly gay player," adding, "the players are diverse enough now that I think they could handle it."

In 2001, ESPN conducted a poll, asking: "If a player on your favorite professional sports team announced he or she was gay or lesbian, how would this affect your attitude towards that player?" Only 17 percent said they would turn against the player, 63 percent said it would make no difference, and 20 percent said they would become a bigger fan.

In 2004, the Chicago Tribune conducted a survey of 476 major league players. It discovered that three quarters of the players said that they wouldn't be bothered by having a gay teammate. In light of changing societal attitudes, it is likely that if a similar survey were done today, that number would be considerably higher.

The breaking of baseball's color line was not simply an act of individual heroism on Robinson's part. As the late historian Jules Tygiel recounted in Baseball's Great Experiment, it took an inter-racial protest movement among liberal and progressive activists, as well as the Negro press, who had agitated for years to integrate major league baseball before Dodgers General Manager Branch Rickey signed Robinson to a contract in 1945, then brought him up to the majors two years later.

Rickey, aware of the many great black ballplayers in the Negro Leagues, believed that the integration of baseball would improve the overall level of play. He also believed -- correctly, it turned out -- that black baseball fans would flock to Ebbets Field to watch black athletes play on the same field as whites.

In 1947, Rickey feared that if Robinson turned out to be a bust as a major league player, it would set back the cause of ending baseball apartheid for at least several years. The same may be true today in terms of the first out-of-the-closet ballplayer. A player of All Star stature would make things easier for everyone who followed.

Almost a decade ago, asked about the likelihood of a gay player coming out of the closet, Philadelphia Phillies manager Larry Bowa told the Associated Press: "If it was me, I'd probably wait until my career was over. I'm sure it would depend on who the player was. If he hits .340, it probably would be easier than if he hits .220.''

Baseball executives certainly recognize that there are plenty of gay--or otherwise sympathetic--baseball fans who would spin the turnstiles to cheer for a homosexual player. Lesbians now constitute a significant segment of the audience for women's pro basketball.

Last year MLB reached a milestone when the Rickets family purchased the Chicago Cubs from the Tribune Company. The family includes Laura Rickets, who not only became MLB's first openly gay owner, but who is also active in the gay rights movement.

No doubt a few of MLB's gay players have considered coming out publicly while still in uniform. Certainly there are gay players in college or in the minor leagues who fantasize about being the gay Jackie Robinson. But so far they have calculated that the personal or financial costs outweigh the benefits. They fear being ostracized by fellow players, harassed by fans, and perhaps traded--or dropped entirely--by their team's management. There is a strong fundamentalist Christian current within major league baseball, which could make life uncomfortable for the first "out" player. That, in turn, could affect his ability to play to his potential. And, initially at least, an openly gay player might lose some of his commercial endorsements.

Of course, if several gay ballplayers came out simultaneously, no single player would have to confront the abuse (as well as bask in the cheers) on his own, as Robinson did.

In 2003, I wrote an article predicting that we can "expect to see an openly gay major league baseball player by the end of the first decade of the 21st century." That prediction was wrong, of course. But how off base was it?

Sometimes baseball is ahead of society when it comes to social change, and sometimes it lags behind. Americans' attitudes toward homosexuality have changed dramatically in the past decade. Can baseball be too far behind?