Cindy Sherman's Untitled Film Stills are on view at The Museum of Modern Art in New York, February 26 through June 11, 2012 and The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, July 14 through October 8, 2012. They compose one part of the Cindy Sherman retrospective, which covers forty years of the artist's work to the present. For further information and directions, visit the SFMOMA and the NYMOMA websites.

Much has been written about Cindy Sherman's Untitled Films Stills and what they tell us about the impact that cinema has on our lives. Yet few commentators have offered to speculate on what cinematic art and artists have taught Cindy Sherman about composing cinematic shots, conveying pictorial illusion, and constructing an overall vision.

I'm referring to the directors and cinematographers whose camera angles, visual styles and pictorial compositions have helped to shape Sherman's evocative pictorial scenes. Or the actors from whom she has learned the gestures and expressions that convey specific meanings and relationships with the viewer. Then there are the designers of mise-en-scène and wardrobe that Sherman approximates, and through which she imparts the cultural signage, iconography, and context that give her photographs their illusion of narrative. And Sherman has somewhere learned to measure out the right amount of restraint and ambiguity to impart a sense there is a hidden story both in her pictures and behind their making, along with the craft of creating a visual ambivalence and tension which piques and then sustains our interest as viewers while inviting us to project onto Sherman's pictures our own imaginariums of fiction and desire.

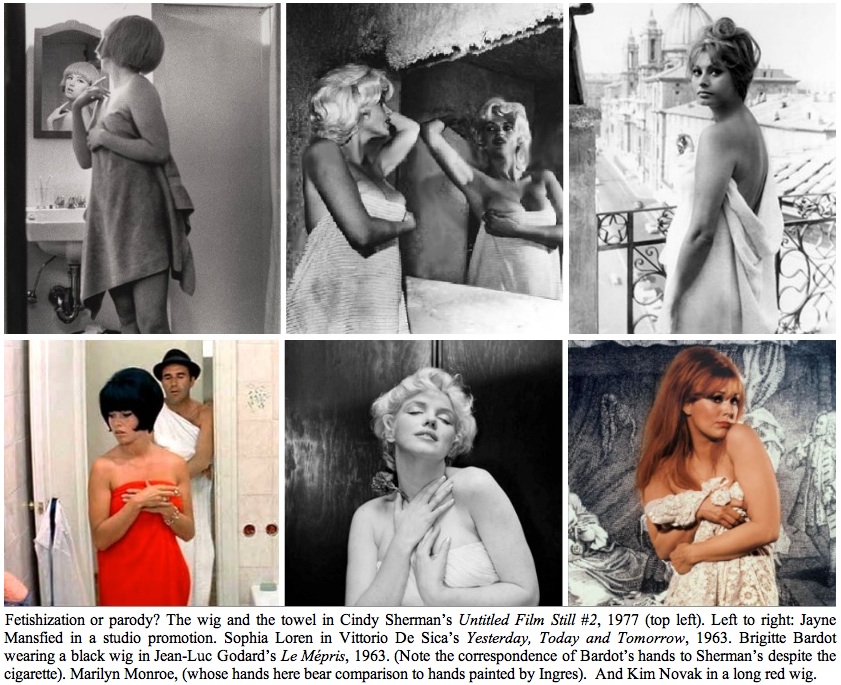

To put it bluntly, whereas most of the writing on Cindy Sherman centers around an analogy of the artist as an actress assuming roles, it strikes me as more accurate to summarize Sherman as a director who oversees every aspect of the feature she is starring in. Perhaps it is the gender barrier once again making critics and commentators more inclined to compare Sherman's accomplishments to actresses instead of to film directors, who are even today largely male. But as I see it, Cindy Sherman is more Orson Welles than Janet Leigh; more John Ford than Vera Miles; more Vittorio De Sica than Sophia Loren; more Alfred Hitchcock than Kim Novak.

The Cindy Sherman I knew in Buffalo, New York, from 1974 to 1977 had a good deal of exposure to foreign cinema and experimental films. Buffalo in the late 1970s was a model laboratory for artists interested in dismantling boundaries between media. Besides the wealth of classes and programs in all the arts supplied by the two Buffalo campuses of the SUNY school system, Buffalo is home to the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Media Studies Buffalo, and the alternative spaces Hallwalls and the Center for Exploratory and Perceptual Arts. At the time that Sherman lived and worked in Buffalo, she was privy to the fluid exchange of influences among the artists and programmers working at all these venues and in all the exhibited media.

In the years just prior to her creation of the Untitled Film Stills, Sherman had exposure to the cinema of the Russian avant-garde, Italian Neorealism, Film Noir and its culmination in Hitchcock, the French New Wave, the films of Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Werner Herzog, the experimental films of Hollis Frampton, Michael Snow, Yvonne Rainer, Babette Mangold, and many more. The Hallwalls complex where she lived in her early twenties regularly received film industry publications containing studio promotions and film rental catalogues overflowing with vintage Hollywood and European film stills -- the kind of raw material an artist with a camera and a predilection for the signage of melodrama rifles through for inspiration. It's this background of influences that has convinced me that Sherman absorbed and assimilated both an intuitive understanding of the commercial film industry and at least an overview of the semiotic film theory that was being circulated all around her during that formative period in her career. All of which tells me that we will learn more about Sherman's Untitled Film Stills if we study them as a response to cinematic techniques and film histories than projecting on them the social and political theories that have been developed in the decades since she made and introduced them.

It's true that to some degree the lessons of cinema bear on all photographers who stage their own photographs. But a photographic series that explicitly models and parodies mid-20th century film with as much virtuoso aplomb as the Untitled Films Stills has to be richly informed by a diversely specialized lexicon of visual techniques and pictorial signage that is the result of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of artists and skilled laborers within the film industry, most of whom go unrecognized.

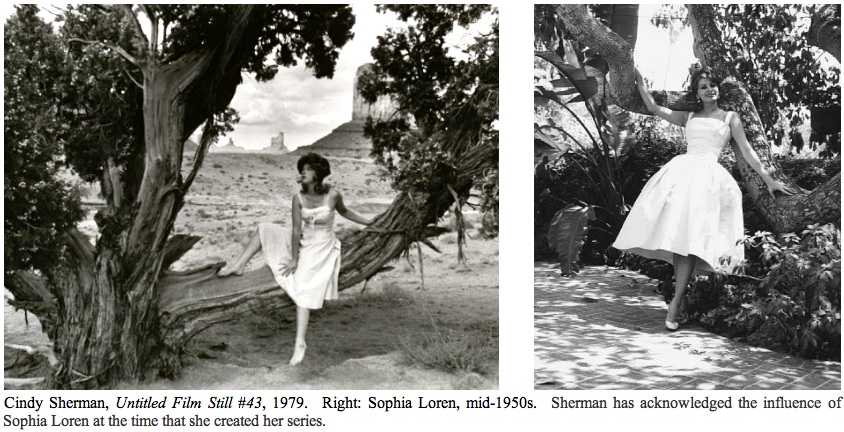

Sherman herself has been coy about naming all but a few cinematic sources for her work--Alfred Hitchcock, Sophia Loren, David Lynch. The artworld avant-garde usually prefers to divorce itself from precedent, not pronounce or reinforce it. But tracing the lineage of an artist's influences is not by any means a diminishment of the artist's skill, especially for someone who is as adept at pictorial composition and iconographic summary as Sherman. After all, artists have for centuries honed their skills and compositions by copying iconography and techniques from the masters who have preceded them until a truly singular artist arrives at a style unique to that artist.

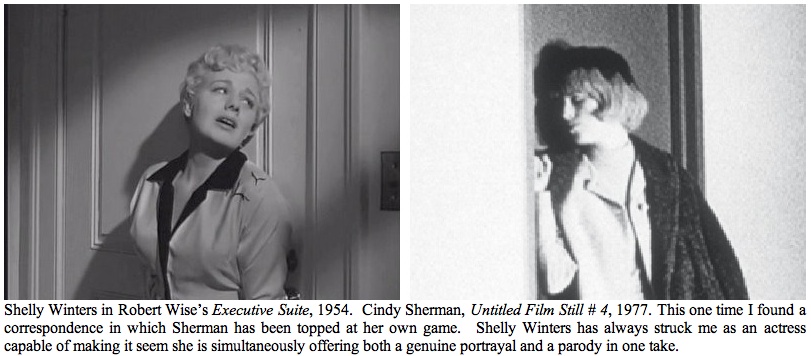

What's different here is that before Cindy Sherman, few photographic artists honed their talents by copying or appropriating prior photographic and cinematic work. In fact, in comparing Sherman'sUntitled Films Stills to the iconic shots we've inherited from the world's innovative film directors, cinematographers and actors, I've found that Sherman not only improves on the masters' techniques, at times her images command more iconic power for being unburdened by the imperatives of real narrative. Art and articulation, after all, are often found to be incompatible, even canceling one or the other out.

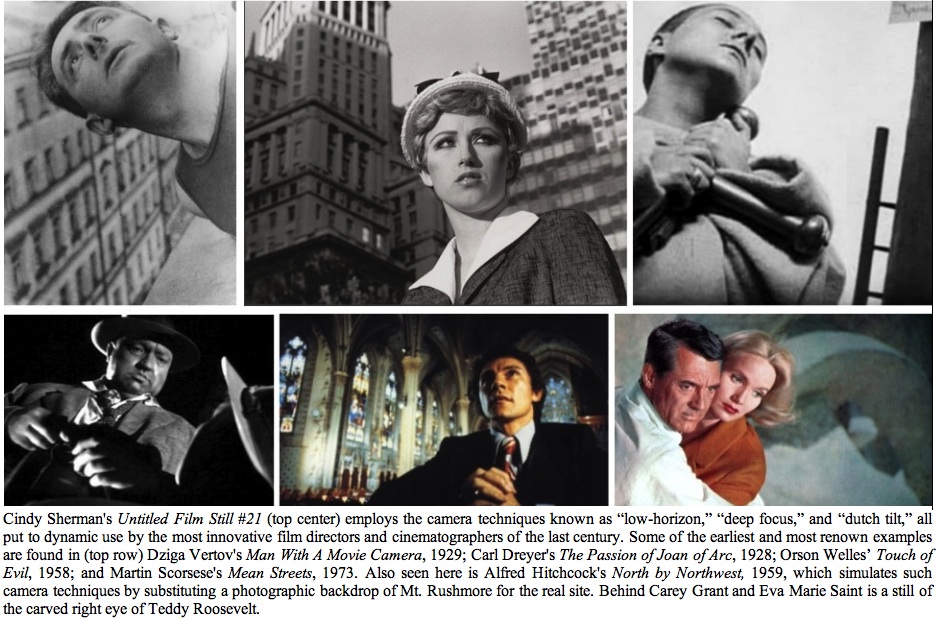

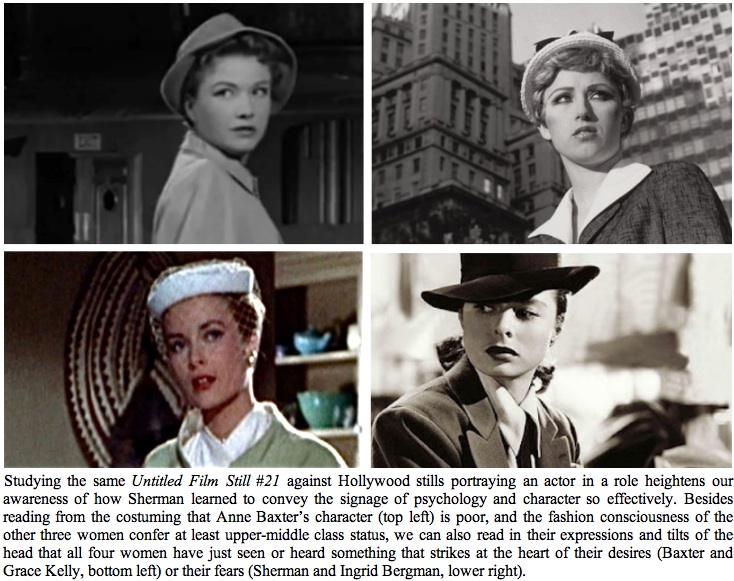

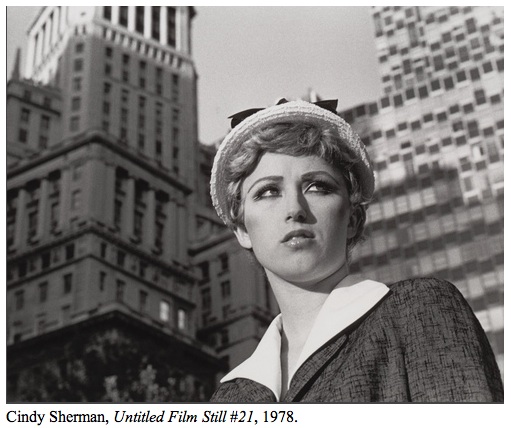

We're left then with guessing at what films Sherman has viewed and borrowed from, though often the answers can be obvious to the average film buff by picking apart the spare mise-en-scène she supplies or comparing the thrift store clothing and wigs she could then afford with those more expensive items the studios have used. Often we can, just by comparing Sherman's work to the films that we've seen, discover what film directors and cinematographers she evokes. Or by analyzing her camera angles and strategies of lighting, we might learn to what extent Sherman's Film Stills are informed by stylistic and formal techniques favored for shooting and editing specific genres of film. We might, for instance, find that Sherman combines such techniques as a low angle shot and a deep focus that renders a facial close-up against towering buildings behind it in an illusionistic perspective that monumentalizes the subject. Or we might notice how Sherman's use of dutch tilts puts her pictorial horizon on a diagonal to effect the viewer's visual disorientation. Sherman is particularly good at infusing a minimalist mise-en-scène with economical, yet culturally loaded, and sometimes semiotically-reflexive, signage about the cultural conditions that cinematic artists would prefer to gloss over or delete altogether. Ultimately, all of these technical devices shape the way that we read Sherman's pictures, to the extent that their combined effect suggests a story is being played out in the picture, when really all the picture is doing is showing us the formal and cultural components that make up conventional storytelling through picture making.

In Untitled Film Still #21, for example, we can see that three distinct camera techniques endow the composition with the dynamic visual tension necessary to arrest our eye once it has been drawn in on the composition. The low camera angle of Still #21, which registers to the eye as a low horizon line, impresses us with the illusion that we are looking up at Sherman's young career woman of the 1950s. The effect is one that unconsiously reinforces our childhood experience of looking up to adults who then seemed beyond our comprehension. We retain some of this experience as adults, in that the illusion of looking up to view a face translates as an encounter with an impressive and inspired personality, a subject seemingly deserving of our respect and interest, if not our apprehension and caution in approaching her. It is this angle that film directors like to use when introducing an ominous or potently forceful protagonist or antagonist.

Still #21 also employs the effect known as a dutch tilt, which is no more than setting the horizon line askew so that it is no longer horizontal but on an incline, as can be seen in the diagonal lines of the buildings seen in the background. It's an effect that destabilizes our sense of control over the world, disorients our sense of place and direction. In Still 21, it instills in us a sense that the young woman is new to, and uncertain about, her place amid the megalopolis of skyscrapers. But the dutch tilt effect is also counteracted by the low angle shot to effect a sense that, despite her present disorientation, she possesses the determination to succeed in the face of adversity.

s third effect at work in Still #21 is the image's deep focus, the clarity of view from the subject's face in the foreground to the buildings in the background. The resultant psychological effect of seeing the young woman's face so large in relationship to the towering buildings in the background defies the logic of real scale to confer an illusionistic estimation of monumentality to the subject, which then further reinforces her worthiness in our estimation.

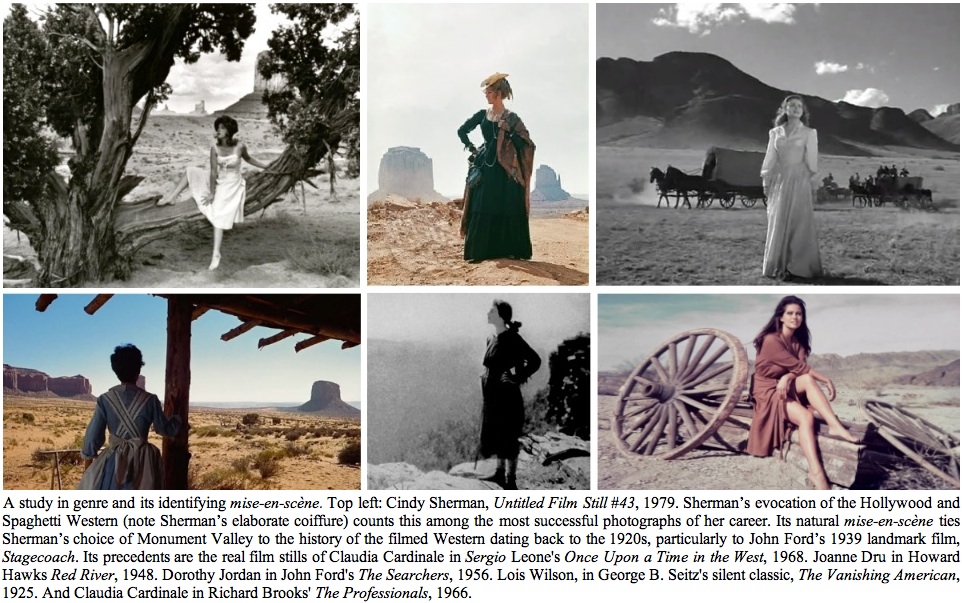

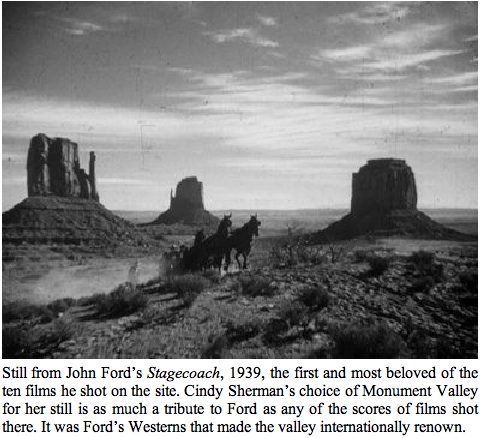

A very different experience is prompted upon encountering Untitled Film Still #43. Less ironic in its appearance than much of Sherman's work, the artist has here captured all the wistful romanticism attached to the image of a lone individual facing the wide open spaces. A young dance hall girl, likely a prostitute, rests in her period petticoat astride an invitingly gnarled desert juniper in the middle of picturesque Monument Valley. Apart from its Western iconography, the image takes on feminist overtones largely by its evocation of the cinematic genre of the Western--one of the iconically male homosocial preserves. Whereas similar images of men in the desert have for centuries been visually archetypal of the human contemplation of the sublime or the spiritual, the lone figure of a woman on the prairie in American culture was made equivalent with the woman's "perennial plight" of "waiting for her man."

But Sherman's choice of Monument Valley is also contextually multidimensional. Fans of the Western as far away as India will no doubt see in Sherman's choice of setting something much more than a picturesque backdrop. Monument Valley is virtually a Western brand, so steep is the signage of commemoration it bears to the scores of directors of the film Western who, since the era of silent films, shot their films in Monument Valley and its nearby environs on the Arizona-Utah border.

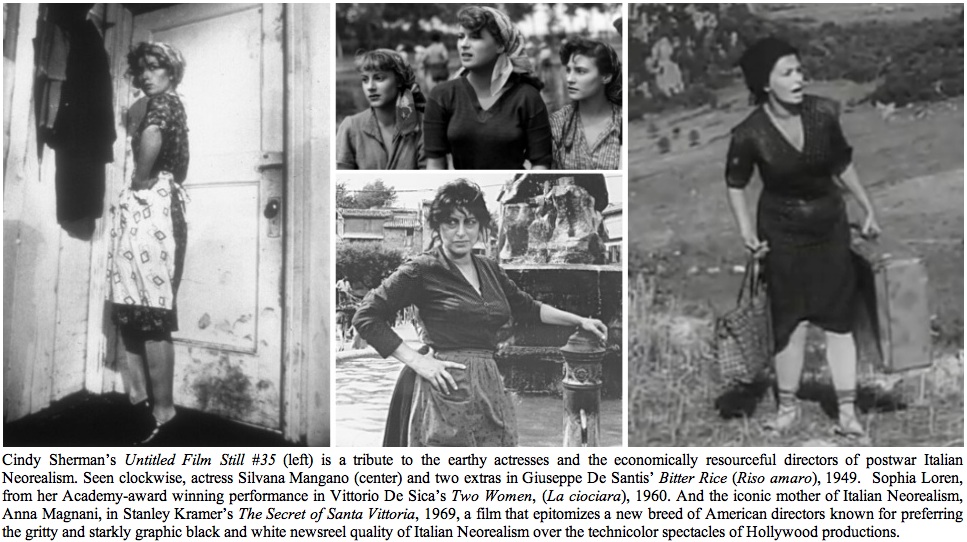

Untitled Film Still #35 offers us another homage, though this one initially strikes modern and affluent audiences as the kind of comic skit on immigrant cleaning ladies that aired on American television variety shows and sitcoms in the 1960s and 1970s. It's a harebrained association that gives way to the realization that Still #35 is Sherman's tribute to the postwar films of Italian Neorealism and the defining performances of the actresses whose critical accolades drew international attention to the challenges facing a nation brought to ruin by fascism and war. Sherman has kept close to the authentic choice of dress, scarf, apron, shoes and stockings that had beome a kind of uniform for the Italian women who had opposed the fascists of Mussolini and Hitler, yet who survived to become the heart and soul of Italy as it struggled through the nation's restoration amid bitter poverty. In this, Sherman's photograph also reflects the economic resourcefulness of some of the 20th century's most brilliant directors--Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica, Luchino Visconti, and Giuseppe De Santis--who with little money shot their scenes in the real homes, on the authentic streets, and with the genuine emotions of a cast of extras peopled by the unpaid Italian locals who lived through the real wartime ordeals being reconstructed on film.

Among the more significant Neorealist films from which Sherman draws her signage is Bitter Rice (Riso Amaro, 1949), by Dino Santis and starring Silvana Mangana. Its story centers around the grueling manual labor of the women working the rice fields of Italy. As an Italian "film reporter" explains in the fictional newsreel being shot at the beginning of Bitter Rice, "Rice has been grown in northern Italy for centuries ... an indelible mark has been left on this land by millions of women whose hands have tended it for 500 years. Hard work that never changes, knee deep in water, bent double under the hot sun. But only women can do it. It needs quick, light hands. The same hands that patiently thread needles and nurse babies."

Another of the Neorealist films summoned to mind by Still #35 is Two Women (La ciociara, 1960) by Vittorio De Sica, the film that won Sophia Loren an Academy Award for her portrayal of a widowed Roman shopkeeper trying to protect her teenage daughter from the horrors of war. Sherman's entertaining commemoration prompts one to ask who else in the affluent American society of the 1970s was thinking about the abject poverty of Italian women thirty-five years removed? At age twenty-five (the age Sherman was when she made the still) I certainly wasn't.

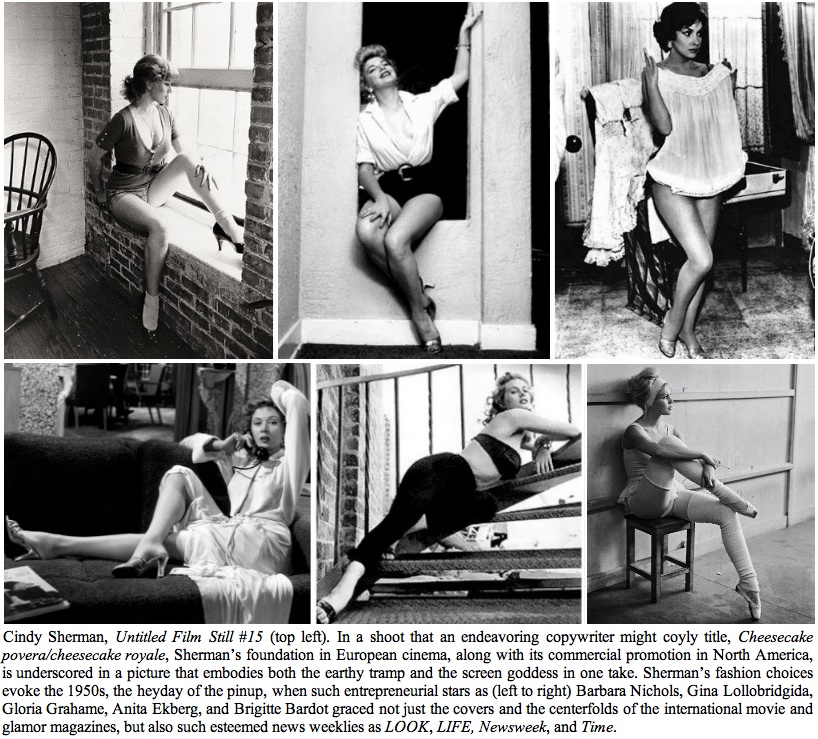

Untitled Film Still #15 also bears the signage of Italian cinema, though now a decade after it began, a time when the growing economy brought with it the sexploitation of internationally renown actresses. Sherman has here evoked the signage of the young urban ingenue of the mid-1950s, the heyday of the movie pinup. In this case the young woman possesses all the earthiness of her humble orgins even as she looks out onto a world of expanding opportunities and finds it is beckoning at her to become the screen goddess she knows she is destined to become. Sherman's fashion sense in Still #15 rated it among the stills that struck early 1980s feminists as too equivocal to be regarded as feminist, though that reading would change radically with the 1990s. (To read my views on of Sherman's contribution to feminism, see my Huffington Post feature, "Gender As Performance and Script.")

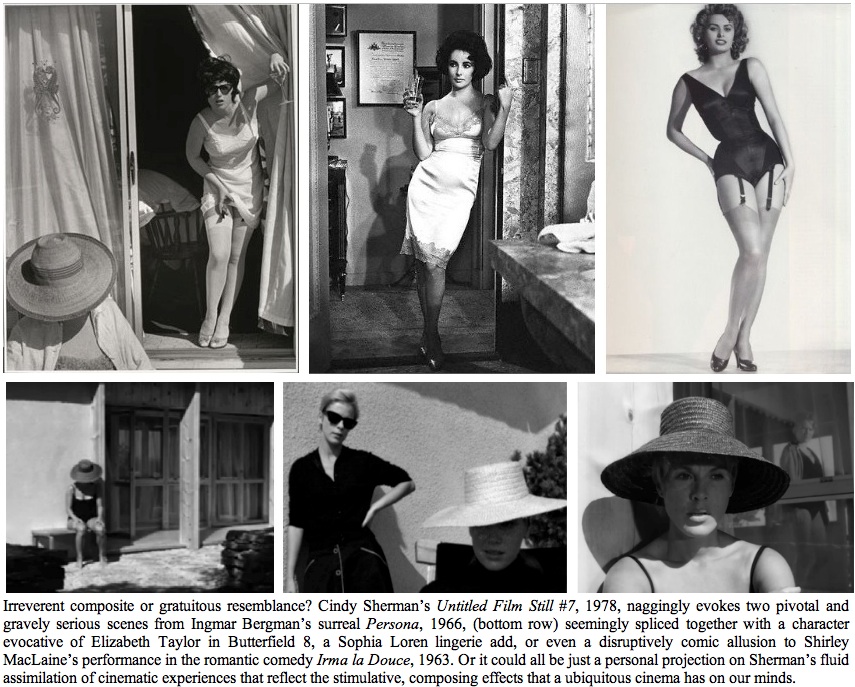

Many of Sherman's photographs are composites, in terms of taking the signage of different films, actors, even genres, and "splicing" them together to convey a unique amalgam of cultural messages, political, sexual and ethnic hindsights. If we recognize the films they loosely quote from, or model themselves after, some of these composite pictures may prove disorienting to us because we recognize that Sherman has assimilated cinematic styles or genres that our categorically-minded sensibilities tell us conflict with our experiences of movies.

Imagine sitting through a half hour of a romantic comedy and finding that the story has suddenly taken a turn to become a dark, suspenseful thriller. Then several moments later, the film again breaks character as characters break out in song and dance. This fractured experience is what some viewers have described upon encountering certain Sherman Film Stills and recognizing in them aspects of various films they've seen.

For my part, I see a clash of genres, films, and moods in one of Sherman's most popular stills.Untitled Film Still #7 presents Sherman in a white slip, white stockings and sun glasses, looking out from an open patio door. Another woman, one with her face obscured by a large straw hat, appears to be asleep on a chair outside an adjacent glass door. To my eye, the mise-en-scène bears a striking resemblance to the famous and strategic patio scene in Ingmar Bergman's 1966 film, Persona. What clinches the references for me is the presence of the sitting woman with the straw hat. Besides that this is the only Sherman photograph known to include someone other than Sherman, the position of the woman exactly corresponds to the placement of the straw-hatted Bibi Andersson in the Persona patio scene, and during which Liv Ullman walks to and fro behind the glass door roughly near the spot in which Sherman stands. But whereas Bergman's patio scene is inhabited by the angst and drama of two Nordic-blonde actresses, Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann, Sherman has assumed the look of a brunette, though she does wear the same style sunglasses sported by Anderssonn in the next scene of the film.

The second film that seems to cohabit in this image is evoked by the figure of Sherman herself, or the Sherman avatar as I call her. Judging from what passes for the picture's early afternoon sun, we seem to have caught the Sherman avatar in the middle of her midday cocktail, a display that reinforces the impression of the woman's exhibitionism while dressing. It is the woman's form-fitting white slip that is the first sign that triggers in my mind a cinematic memory apart from that of Bergman's Persona. Another is the cavalier manner in which she holds her cocktail glass with the same raised hand used to sweep back the draperies from the door that puts her in full view of onlookers, and frames her in the bifocal composition. She is one of Sherman's best-choreographed figures, in that Sherman's right hand, in the manner of the many classical Greek and Roman sculptures of Aphrodite, counterbalances the upsweep of her left arm by provocatively hiking up her white stocking just enough to begin raising her slip's hemline--and just stoping short of bearing all. In this one slight gesture, Sherman brilliantly conflates the iconography of classical beauty with the baser instincts of the burlesque.

As for the film I'm reminded of, the reading of the shot's signage of alcoholism and exhibitionism, along with Sherman's brazen pose, bears all the hallmarks of Elizabeth Taylor in Butterfield 8--whom we may recall is playing a hard-drinking, pill-popping, prostitute. At the same time, the white stockings and garter, along with the position of Sherman's legs, recall for me those famous 1950s lingerie shoots with Sophia Loren, while the pose itself, along with the styling of her wig, compels me to think of Shirley MacLaine in Irma la Douce. The overall effect displays Sherman's open delight taken in fusing the signage of so-called high and low art--here with the valences of gentility and vulgarity--in one composition that keeps from tipping too far in favor of one proclivity or the other. With so many correspondences at work in Still #7, the still suggests that we see best into Sherman's pictures when we come to them well armed with an ample experience of screenings.

What passes for the simulated film's "action" and "story" in Untitled Film Still #7 accounts for what may well be Sherman's most reflexive strategy of her career. When we see that the Sherman avatar looks out directly at the camera, we also notice she wears an expression of focused exasperation. The reading is that she has only at that instant come to see she is being photographed--which corresponds with Sherman's narrative genesis of the series as a fictional record of the roles, and at times the private moments, of a prominent motion picture actress. Considering that the "paparazza" just sighted by the Sherman avatar is herself, or at least is set up by herself, the still composes a richly reflexive irony, the kind of tautological art-parlor game admired by 1970s artists and analogized as two reflecting mirrors, each directly reflecting the other so that the circle of infinity is made photographically complete.

It is this mirroring moment that makes me realize that without the anchorage of Sherman's art to the world, Sherman's photographic domain would be comprised of empty, repetitive narcissism. And I mean in the manner of that scene in the film Being John Malkovich, where Malkovich enters the metaphysical portal to his own mind, finding a breech in the continuum of reality that reduces for him all humanity and existence to being, seeing, speaking nothing but the personage, image, and name, "John Malkovich." It's a scene that, like Sherman's Still #7 paparazza moment, reminds us that solipsism renders us incapable of enjoying any and all worthwhile functions in the world, or in this case it comes close to producing an art without a purpose.

But then Sherman understood even in her early twentes that the real challenge for a first-rate iconographer is to make the subjective experience a collective one. The fact that so many people regard the Untitled Film Stills to be both archetypal to society as a whole and identifiable in their lives personally indicates that audiences respond to her still photographs in the same fashion that they do upon watching a motion picture. This is why, after thirty-five years, Cindy Sherman's Untitled Film Stills have virtually become the property of the public domain. They are becoming too prominently a part of popular and cultural history to be dismissed as being without some form of intermediation that allows people to read them on so many levels. Cinema is that intermedia between the audience and the Sherman film still. Which is why even calling them "ironic" is to tell only half the story.

It is precisely because so many people recognize in Sherman's work not just their own viewing experience of film, but the personal catharsis they find in it for desires unfulfilled, that we should regard Sherman's Untitled Film Stills as transcending the domain of visual art and composing more a cinema of shots. And why not. Sherman is, after all, filling the void left in the demise of naturalistic and figurative pictorial painting, except that instead of descending into the history of painting, or for that matter of conventional photography, she has made a photographic evocation of cinematic history her pictorial, structural, and canonic legacy.

This is more than a case of an artist putting her finger on the pulse of a drifting civilization. It seems much more a case that the general, secular public has caught up with Sherman's signage because, in a little more than a half century, a significantly large segment of the public's world views and desires have become as much, if not more, shaped by cinema, television, even advertising, than they are by religion, ethics, and utopian political and economic systems.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.