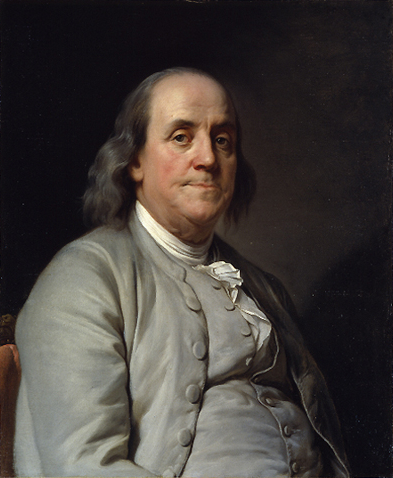

Permit me a story.

After a hot Philadelphia summer of very much wrangling, the day had arrived to sign our nation's new Constitution. Having put my own name to it, I was preparing to enjoy some fresh unpolitical air, when an agitated woman, a Mrs. Powell, stopped me just outside the hall. What type of government, she demanded, have you delegates given us?

"A republic, madam," I replied. "If you can keep it."

My countrymen, it pleases me to no end that you have kept it. Mostly.

But like a bride with two grooms, you face a fateful point of decision.

With this in mind, I offer for your consideration these three wise rules to guide your choice on Election Day.

1. The President Must Believe in Science.

There are few times more pertinent to reflect on the public benefits of science than in very large storms. Though not given to horn-tooting, it may interest observers of this week's torrent that I was the first to track the progress of Nor'easters, theorize on high and low pressure fronts, chase storms (on horseback), and map the Gulf Stream: Thus, with justice, your Founding Weatherman.

To limit the effects of fires and other disasters of nature, I organized Philadelphia's first fire brigade and, with public support, established a network in all thirteen colonies; a mission taken up admirably by your Federal Emergency Management Agency. Now I understand Mr. R______ has said he wanted to absent the national government from this mission and give it either to states, or preferably, to profit-making enterprises. I leave those of you with flooded basements to consider this proposal.

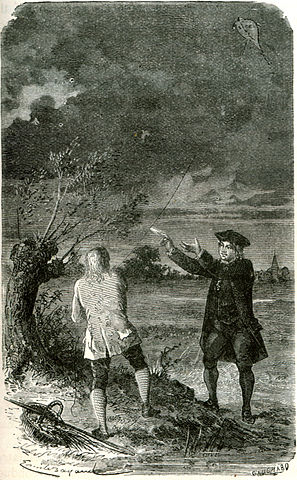

He who would serve the public, in short, must take science seriously. When I first began my electrical experiments, I was told that electricity was the stuff of parlor games, and that I should not bother myself with such an unproven source of energy. It pleases me that in the 21st century, the candle industry no longer carries the same political clout; yet the most useful ideas (and gravest warnings) of America's scientists are falling on politicians' deaf ears.

This is not a new problem. In great storms, many churches used to rely upon the ringing of bells as the surest preventative against lightning. After my well-reported kite flying and subsequent invention of the lightning rod, several of these priests refused my innovation, preferring their faith-based approach. While not denigrating these preachers or their lightly-singed frocks, I submit that the president's decisions must derive more from hard data than from faith alone.

Energy improvements were a particular specialty of mine. In the 1730s I took to painting fruit sheds with black paint after having observed that the color black retained more of the sun's rays. I developed the Franklin Stove as a way of producing more heat from less wood (and with much less smoke). These innovations in energy efficiency saved both pennies and trees, and though they have begun a return to fashion, are strongly opposed by one of the two major parties. I submit this too for my countrymen's consideration.

Energy improvements were a particular specialty of mine. In the 1730s I took to painting fruit sheds with black paint after having observed that the color black retained more of the sun's rays. I developed the Franklin Stove as a way of producing more heat from less wood (and with much less smoke). These innovations in energy efficiency saved both pennies and trees, and though they have begun a return to fashion, are strongly opposed by one of the two major parties. I submit this too for my countrymen's consideration.

Progress in the practical application of science and energy means progress for the public. Only one of your two candidates seems to agree.

2. The President Must Be A Man of Projects.

Mr. R_____, having succeeded at business, claims that there is a bright line between the usefulness of public and private projects. If such a line ever existed, I dedicated my career to demolishing it.

I spearheaded model fire and police departments, started America's first hospital and circulation library, modernized the postal network, and created insurance associations for tradesmen. Whether as elected official or private citizen, I attacked these common needs with the ingenious use of whatever resources lay at hand. During the War of Independence, I traveled to Massachusetts to inventory armaments, set rations, and draw up rules of army conduct at General Washington's side. I was something of a policy wonk.

Nevertheless, there always is a right and a wrong way to make a public project.

I believed, and Mr. O______ agrees, that government must create opportunity rather than dependence. If implemented poorly, public aid "tends to encourage idleness and prodigality, and thereby to promote and increase poverty, the very evil it was intended to cure" ("On the Laboring Poor," 1768). Projects must be judged not by Intentions but by their Results.

And though no stranger to profitable business, I was equally frustrated by those who placed their own money above the public good. In the Pennsylvania of my day, there was a class of proprietors -- descendants of William Penn -- who sought to exempt themselves from bills of revenue and made members of the Assembly swear never to raise their taxes (is it true that many current legislators bind themselves by this same oath?). By contrast, the very first law I proposed, for a city police force, was to be financed by a tax "proportion'd to Property." As I often said, "The general foible of mankind, is the pursuit of Wealth to no end."

And though no stranger to profitable business, I was equally frustrated by those who placed their own money above the public good. In the Pennsylvania of my day, there was a class of proprietors -- descendants of William Penn -- who sought to exempt themselves from bills of revenue and made members of the Assembly swear never to raise their taxes (is it true that many current legislators bind themselves by this same oath?). By contrast, the very first law I proposed, for a city police force, was to be financed by a tax "proportion'd to Property." As I often said, "The general foible of mankind, is the pursuit of Wealth to no end."

(At the other end of the spectrum, I was often just as frustrated by unreasoning crowds. I called the Tea Party -- the First One -- an "act of violent injustice on our part." I hope such angry Impulses in our republic may yet be controlled.)

I located America's strength not in the palaces of the wealthy or the din of the crowd, but in the well-being of what I called the "middling people." These were the men and women who walked on cleaner streets, had access to libraries and hospitals, lived safer from storms, and had more say in their government as a result of my projects. I doubt any of these efforts would have earned the support of Mr. R_______ or his party.

Some argue loudly that man's highest purpose, and firmest political principle, is to be left alone.

"He that drinks his cider alone," I used to say, "let him catch his horse alone."

Self-reliance and community support are not opposites but reinforcements to one another. Mr. O______, for all his disappointments, has seen his public projects bear encouraging fruit. A president may fail, but it is in America's interest that he never stop trying.

3. The President Must Tinker.

In eighty-four years, I never left well enough alone. In my laboratory, my stove, bifocal glasses, and electrical tubes were the subject of perpetual reinvention.

I brought this same spirit to political life. When I sought to build Philadelphia's first hospital, there were not enough voluntary funds, and the Assembly was most reluctant to appropriate the needed amount. So I tried something altogether new: I convinced my fellow Assemblymen to pass a bill which appropriated the sum of £2000, provided a similar amount could be raised through private donations. The legislature had their political cover, the public its incentive, and soon enough the funds were raised -- and matched. It was the country's first "public-private partnership," and as I wrote in my autobiography, "I do not remember any of my political Maneuvers, the Success of which gave me at the time more Pleasure." (p.138)

Mr. O______'s signature achievement, regarding the health of his fellow citizens, will try (in its little-known passages) nearly every known method to bend the curve of these expenses, from electrifying medical records (I approve!) to encouraging collaboration among doctors. It seems, in short, that contrary to what is generally thought, a spirit of tinkering lies at the very heart of this reform.

When considering our laws, and even our Constitution, my readers should be reminded that, however much pride a man has in his carriage, he must still repair its wheels. From the drawing of electoral districts to the finance of campaigns, from the improvement of schools to the laws of citizenship, the president must fearlessly tinker until a better balance is found.

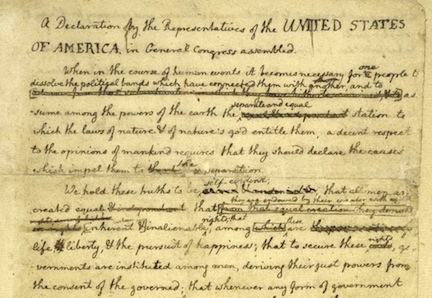

Thomas Jefferson was a great patriot and friend, but where I thought his expressions in need of tinkering, there also I did not hesitate. As we read through the first draft of his Declaration of Independence, I came upon the phrase, "we hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable." With an eye to simpler common sense, and using a printer's careful strokes, I crossed out those three words and wrote, "self-evident."

In America, even the most sacred laws can bear correcting.

Tinkering with Independence.

I do not consider Mr. O______ to be a man without flaws. My Advice to him would be threefold: First, make humor a more effective political weapon -- voters and politicians in a good mood are more likely to make deals; second, when you have a useful idea, for the love of God, take your name off of it -- politicians are jealous creatures (hence, no "Madison Constitution" or "Jefferson Declaration of Independence"); and finally, resist the distance of your office -- bring the people with you on your great projects, and the politicians will surely follow behind.

The four years ahead look to be steep ones, and I do not envy the president's great task. But on a dark night, in a terrible storm, I put my fragile kite skyward and captured lightning.

If I could do it, Mr. Obama, so can you.