U.S. presidential candidate Bernie Sanders has reopened the health care debate by urging America to adopt a system more like that of other wealthy countries. In Sunday night's Democratic presidential debate in Flint, Michigan, he said, "When we talk about Europe and their pluses and minuses, one thing they have done well that we should emulate ... is guaranteed health care for all people."

He pointed out that even though the U.S. is the only major country on Earth that doesn't guarantee health care to all people as a right, we spend far more per capita than the UK, France and other advanced countries. Yet, even though he's right to think that we need a health care system more like those in Europe, his platform is under attack, not just from the right, but also from the left. Here is why I think his critics are wrong.

What to call it?

Sanders says he wants a health care system like those of other wealthy countries -- one that provides better results at a lower cost than the one we have. Unfortunately, there is no generally accepted term that covers all such systems as a class.

Sanders calls his plan "Medicare for All," but that is misleading. As we will see, his proposal -- at least the brief version posted on his campaign Web site -- differs from Medicare in some important ways. It also differs from many of the systems in other countries that he admires most.

Liberals tend to call Sanders' plan a "single-payer" system. That is correct, in that Medicare for All would in fact be a system under which a single agency would directly pay health care providers with funds from the government budget. However, many of the best health care systems of other wealthy countries are not single-payer systems in that sense.

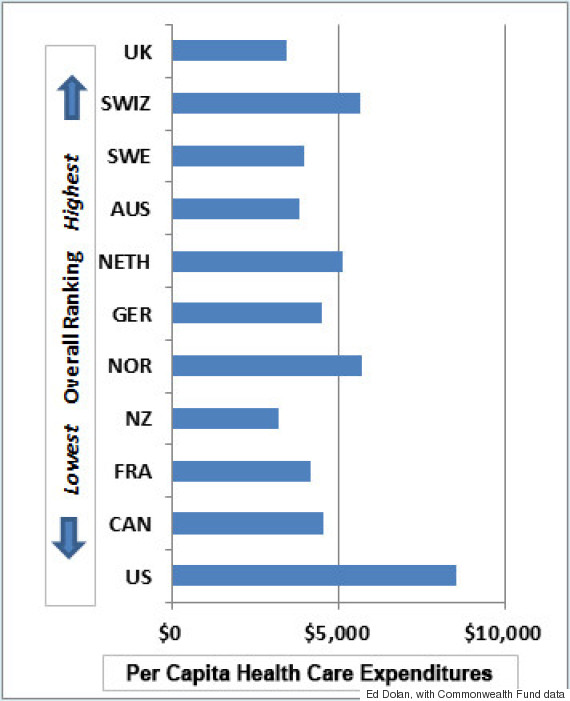

The U.S. ranks last in the fund's overall evaluation of health care, despite having by far the largest per capita expenditures.

Their plans are surprisingly diverse. Some, like those of Germany and France, funnel payments through multiple independent insurance funds. Others, including those of the UK and Canada, are more decentralized than the "single payer" label suggests. None of them covers 100 percent of national health care expenditure.

Conservatives describe the health care systems of Scandinavia, Germany, France and other wealthy countries as "socialized medicine," but that term doesn't uniformly fit, either. Socialized medicine suggests something like the U.S. Veterans Administration health care in the U.S. -- a system that not only features a single payer, but one in which doctors are salaried government employees and hospitals are government-owned. That description, too, fails to capture the diversity of foreign health care systems, where we find a kaleidoscopic mix of salaried and fee-for-service doctors; for-profit, private not-for-profit, and state-owned clinics and hospitals; and both unified and decentralized payment mechanisms.

We could stick with "high-performing health care systems of other wealthy countries," but that is too long-winded. For this post, I will shorten that to Euro-style health care, despite the obvious problem that Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Japan also fit the pattern in many respects.

Enough with terminology. Let's turn to Sanders' critics, starting with those on the right and then moving to critics on the left.

Conservative Myth #1: The U.S. already has the world's best health care system.

Many conservatives think, or at least pretend to think, that the U.S. already has the best health care system in the world, or at least that it did before the advent of Obamacare. Senate leader Mitch McConnell and former House Speaker John Boehner are both on record as having said so. A survey from Harvard University, taken not long before the passage of the Affordable Care Act, found that 68 percent of Republicans (but only 32 percent of Democrats) thought the U.S. health care system was the world's best. To support that belief, conservatives often note that world leaders like former Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, Jordan's late King Hussein and the Shah of Iran have all sought health care in the U.S.

Unfortunately, hard data do not support that optimistic view. One of the most detailed recent comparative studies of health care systems in wealthy countries comes from the Commonwealth Fund. The following figure shows its ranking of eleven health care systems along with data on expenditures per capita (evaluated at purchasing power parity to avoid exchange rate distortions):

The U.S. ranks last in the fund's overall evaluation of health care, despite having by far the largest per capita expenditures. The Commonwealth study is not the only one to have reached that conclusion. This earlier post discussed other rankings that agree.

Conservative Myth #2: European health care saves costs only by severely rationing care.

The second conservative myth is that Euro-style health care achieves lower costs only by employing a degree of rationing that would be unacceptable to Americans. Here, for example, is David Brooks, writing in the The New York Times:

Sanders would create a centralized and streamlined system. His approach would also, as in Europe, reduce the rate of medical progress, increase the rationing of care, increase the wait times for patients, induce many doctors to retire, and centralize decision-making.

In a recent televised debate, Presidential candidate Ted Cruz put it even more bluntly:

Socialized medicine is a disaster. It does not work. If you look at the countries that have imposed socialized medicine, that have put the government in charge of providing medicine, what inevitably happens is rationing.

Canada is Exhibit A for many who make the rationing argument. Consider, for example, this explainer video from Vox, titled "What is Single-Payer Health care?" After noting that such a system could save administrative costs, the narrator says, "But there's a catch." The catch is said to be longer waiting times and other limits on services, illustrated by a graphic showing that waiting times for health services are longer in Canada than in the U.S.

Most wealthy European countries do better than either of their North American peers when it comes to rationing by waiting and still manage to spend less.

Detailed data from the Commonwealth Fund report show how unfair the charge of rationing is, especially when based on a comparison with Canada. Of the 11 countries covered in the survey, the U.S. ranks last overall, and Canada is next to last. One of the main reasons for Canada's poor performance is its poor record on measures of rationing, where it has the lowest ratings of the countries surveyed.

- 48 percent of Canadians reported an emergency room waiting time of over two hours (11th place) compared with 28 percent in the U.S. (7th place) and 14 percent in New Zealand (1st place).

- 38 percent of Canadian doctors reported that patients had difficulty getting specialized tests like MRIs (10th place) compared to 23 percent in the U.S. (7th place) and 3 percent in Switzerland (1st place).

- 18 percent of Canadian doctors reported a wait of four months of more for elective surgery (9th place) compared to 7 percent in the U.S. (6th place) and 1 percent in the Netherlands (1st place).

To compare the U.S. with Canada in terms of rationing by waiting, then, is to make a sub-par system look better by comparing it with one that is truly terrible. Most wealthy European countries do better than either of their North American peers when it comes to rationing by waiting and still manage to spend less.

Instead of rationing by waiting, the American system practices rationing by cost. Relatively few private plans, whether employer-provided or individual, give free access to a full range of providers, drugs and services. Most middle-class insurance plans steer their members toward hospitals and doctors who are in a preferred provider network and drugs that are on the company's preferred list. The uninsured often find themselves rationed out of anything but emergency services by high prices.

The burden of rationing by cost shows up clearly in the Commonwealth study:

- 37 percent of Americans reported that they did not fill a prescription, skipped a test or treatment, or failed to visit a doctor when ill -- the worst of all countries. In Canada, the figure was 13 percent, a respectable 4th.

- 28 percent of Americans reported that their insurance company denied payment or paid less than expected for treatments they received, the worst of all countries. In the top-ranked countries, Norway and Sweden, the figure was 3 percent.

What is more, the pressure toward rationing by cost is intensifying. A recent New York Times article describes the situation in these terms:

Once emblematic of everything wrong with health insurance, the health maintenance organization is making a grudging, if somewhat successful, comeback. But its reputation for skimping on care has so tainted the plans that the insurers and companies resurrecting them have gone through innumerable steps to try to avoid using the term H.M.O. ... Despite the stigma and many failed efforts, insurers say they are eager to push a revamped version that revives many of the same features that restrict choices as a way of lowering costs.

In short, far from achieving their cost savings through rationing, European systems provide more timely care with fewer people skipping needed services for economic reasons.

Liberal critics focus on cost

Unlike conservatives, liberal critics, by and large, approve of Sanders' Medicare for All plan in principle. They instead focus their criticisms on its cost.

The most widely publicized critique comes from Kenneth Thorpe of Emory University. As this discussion explains, Thorpe estimates that Sanders' plan would be almost twice as expensive as the candidate claims. Instead of leaving most middle-class households better off, Thorpe claims the Sanders plan would make 71 percent of households worse off, when the taxes needed to fund it fully are set against savings in health care costs.

I find Thorpe's analysis disingenuous. The problem is that he construes Sanders' plan in a naively literal way that makes it very different from the health care systems of Europe as they actually operate.

European systems provide more timely care with fewer people skipping needed services for economic reasons.

The first difference concerns just who pays for what under high-quality, low-cost Euro-style systems. When many Americans think of European health care, they assume that the government pays for everything, providing a broad range of services at no charge to the consumer. That is not strictly true.

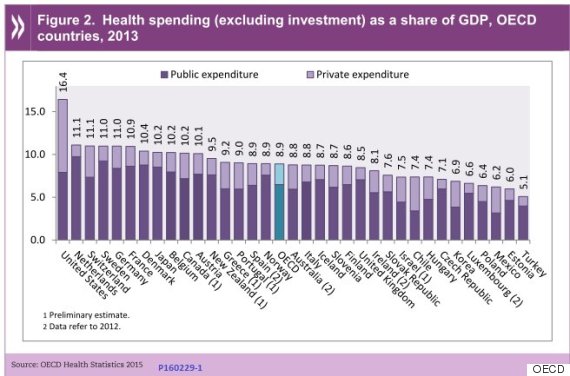

The following chart, reproduced from a 2015 report from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, shows that in other wealthy democratic countries, governments do pay a larger share of health care costs than in the U.S., but they do not by any means pay for everything. The government share of total health care expenditures ranges from nearly 90 percent in Sweden and the UK to around 75 percent in Switzerland, compared with a little under 50 percent in the U.S.

The reasons for the substantial private health care expenditures vary from one country to another. Most countries expect copayments for some, if not all, services and medications. In many, people purchase private insurance to cover services not provided in the government's basic package -- private hospital rooms, for example. Some countries do not fully cover dental and vision services. (However, most Euro-style systems have special mechanisms in place to shield low-income families from some of these cost-saving measures.)

One of the reasons that critics like Thorpe come up with such high cost estimates is that they take at face value the version of the Sanders plan that is found on his campaign Web site. That version promises to "cover the entire continuum of health care, from inpatient to outpatient care; preventive to emergency care; primary care to specialty care, including long-term and palliative care; vision, hearing and oral health care; mental health and substance abuse services; as well as prescription medications, medical equipment, supplies, diagnostics and treatments."

I do not think we have to take that language literally in estimating the cost of translating Sanders' political aspirations into a specific program for implementation in the real world. The very fact that Sanders describes his plan as "Medicare for All" suggests that a final version is likely to include deductibles and copayments similar to those in Medicare as it now exists for seniors. Nor would we need all of the features of the Web site version of the plan in order to meet Sanders' often-repeated goal of equaling the quality and cost performance of other countries.

The hard part lies ahead

It is easy to criticize a campaign slogan and to inflate the cost of ambitious aspirations. Liberal critics, who ostensibly share Sanders' aspirations, ought to put their energies into the hard part -- filling in the details that would allow the U.S. to equal the cost performance of the best Euro-style health care systems without loss of quality.

Including Medicare-style deductibles and copayments would go a long way toward closing the gap between Thorpe's estimates of the costs of Sanders' health care plan and the candidate's own estimates, but it would not entirely close it. There are many other problems to deal with.

To date, Sanders has focused on two sources of potential cost savings. Administrative costs are one. Sanders' campaign website does not give an exact estimate of savings, but Sanders' policy director Warren Gunnels reportedly estimates that administrative savings from his plan would reduce total health care spending by 13 percent. Thorpe says it would save 4.7 percent. If we split the difference, the savings would be a little under 9 percent.

But reducing per capita health care spending to the level of the Netherlands (the most expensive after the U.S. among the eleven covered in the Commonwealth study) would require U.S. spending to fall by 33 percent. To get to the level of the UK (the least expensive of the eleven) would require a 60 percent cut. So, even viewed optimistically, administrative savings are just a start.

A single government payer would have more bargaining power.

The second major saving claimed by the Sanders team comes from lowering the price of prescription drugs. Total prescription drug expenditures in 2014 came to an estimated $297 billion, a fraction less than 10 percent of total health care costs, on prescription drugs. Cutting that in half -- a truly heroic accomplishment -- would still save only another 5 percent of total health care costs.

So, beyond prescription drugs and administrative costs, where would the additional 20 to 40 percent saving come from that would be needed to bring U.S. health care costs down to the level of the best performing Euro-style systems? There are only two possible sources: cuts in quantity of services or cuts in prices.

Cutting quantities is not as easy as it sounds. To be sure, there are some areas where the U.S. does seem to provide excessive services or procedures. For example, the U.S. rate for Caesarian sections is reportedly about 30 percent, more than double that of the Netherlands (13 percent) and nearly double that of Finland, Sweden and Norway (all close to 17 percent).

On the whole, however, as health care economists like Princeton's Uwe Reinhardt note, the quantity of health care services provided in the U.S. is actually lower than in other advanced countries. It does not seem realistically possible to cut service quantities further while extending health care coverage to the 13 percent of Americans who remain uninsured, even under the Affordable Care Act, and to do so without any loss in quality of care.

Prices are the "elephant in the room," says Reinhardt. Medical prices in the U.S. are reportedly 60 percent higher than in an average of 12 other high-income countries. For individual procedures, the differences are often greater. For example, an appendectomy that cost $7,962 in the U.S. cost $2,943 in Germany and $3,739 in Finland. What is more, the prices of services like an MRI or colonoscopy, can vary by a factor of two, three or more even with in a city.

Worst of all, says Reinhardt, "Fees in the private health care sector have been jealously guarded trade secrets among insurers and providers of health care." That makes it impossible for consumers to shop around for the best price, as Forbes writer Kate Ashford found from personal experience when she tried to find the best deal on an MRI. In practice, it can be difficult or impossible for consumers to shop for medical care the way they would for a set of snow tires.

The present trend toward mergers and consolidations demonstrably pushes up prices.

Liberal critics don't even pretend to address the problem of health care prices. The widely cited Thorpe study simply assumes that prices under the Sanders plan would be an average of the prices now paid by private insurers and the modestly lower prices now paid by Medicare.

The day after a Sanders inauguration, his health care team would have to get to work on tackling the elephant in the room. Unfortunately, there is no single solution to the problem of high U.S. health care prices. Instead, the problem would have to be approached one piece at a time. Coordinated bargaining for lower prescription drug prices is just a start.

Lowering the prices charged by the most expensive hospitals to those charged by the most effective ones would help -- and no, they are not necessarily the same hospitals. A single government payer would have more bargaining power. Greater transparency in pricing would help, too. So would greater competition among hospitals. The present trend toward mergers and consolidations demonstrably pushes up prices.

Another reason for the higher cost of U.S. health care services are higher earnings of physicians. U.S. doctors earn considerably more than their European counterparts do, even when we adjust fees for differences in expenses and cost of living. But changing compensation practices for American doctors would not be easy without other, more far-reaching reforms. For example, making higher education tuition-free, as Sanders has proposed, following the policies of many European countries, would reduce the burden of student debt with which American doctors begin their careers. And less adversarial systems to deal with malpractice claims free European doctors from a major cost item while giving them less incentive to practice unproductive defensive medicine.

The bottom line

It is hard not to conclude that Sanders is right to think that America needs a health care system more like those in Europe. True, his Medicare for All plan is still more aspirational than operational, but what do other candidates offer? Hillary Clinton proposes building on Obamacare, but there is nothing in the byzantine complexity of the Affordable Care Act that makes it easier to solve any of the cost and price problems we have discussed, and many things that make it harder. Republican candidates have a field day enumerating the problems of the ACA, but offer only the vaguest suggestions of what they would offer in its place.

So I say, better to go with someone who has the right aspirations and hope his team can work out the details as they go along. Otherwise, we are stuck with the health care mess we have, or with a worse one.

Follow Dolan's blog at www.economonitor.com.