As we commemorate 100 years since the start of the First World War and after passing through the atrocities and destructive treaties of WWII, these days we inch closer to a third installment of much the same, without giving it a lot of thought. Pope Francis said on September 13th, at a memorial for soldiers slain in Redipuglia, Italy, "even today, after the second failure of another world war, perhaps one can speak of a third war, one fought piecemeal, with crimes, massacres, destruction."

But while this one quote from the Pontiff is thought-provoking, I typically shy away from religious figures to make sense of the world around me; I turn instead to filmmakers. As Venice Days delegate and Italian journalist Giorgio Gosetti pointed out, during our recent interview, "artists are strange enough to understand someway, I don't know how, I don't know why, before the rest of the world what could be possible and what could be considerable." The great wisdom of cinema has guided me well thus far, and I've learned more from the seventh art, and the artists who create it, than any schoolbook could ever teach me.

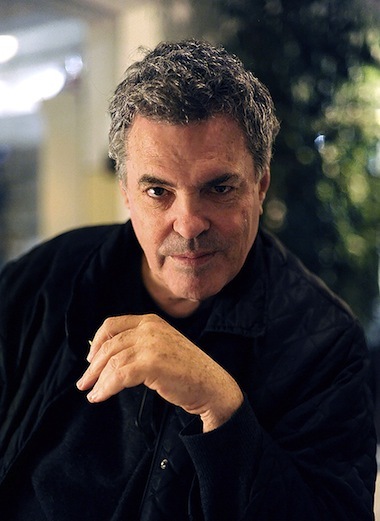

Among the greatest of teachers, I personally hold Amos Gitai in a top position. His work -- such as his latest masterpiece Tsili which premiered Out of Competition at the 71st Venice Film Festival -- is insightful, groundbreaking, thought-provoking, strong, full of emotions and always entertaining.

The best example of cinema with a conscience.

Gitai's ideas are constantly in motion, his themes change from project to project, and he's not stuck in some self-imposed concept of the tortured artist who needs to prove something with his work. He simply creates, and then lets his work go, to reach the far-flung recesses of this world, helping to unite the divide. It's no accident he's a trained architect, that's what he studied both in Israel and later at Berkeley. Because truly, if anyone knows how to build cultural bridges, it's Amos Gitai.

Perfectly aligned with both his work and character, Gitai is also a wonderful interview. Enthusiastic, knowledgeable, fair, politically aware yet never sounding judgmental, ever the gentleman and lacking any hint of condescension, he made for the most pleasant afternoon chat in Venice. After out talk, I felt like I could have called it a day, my festival concluding on the highest note.

After the press screening of Tsili, I eavesdropped on two Italian gentlemen talking about the film. One said to the other "I think Gitai is reinventing cinema, trying to teach us a new way of watching movies, much like Last Year at Marienbad did in the Sixties." Are you trying to teach us a new way of watching film?

Amos Gitai: Yeah. I think that we have to try to do a few things at the same time when we make a film. Which is complicated but necessary. So we have to create a narrative, or a story or a thematic that we would like to evoke, but we also have to innovate in the form. In my mind, cinema is really going in a very unpleasant direction, that is fighting again and again to make more and more spectacular and violent, and we have to go to simplicity. We have to speak about understatement, we have to go back to some really basic ingredients from the beginning of performance, and work with it. That's also a suggestion for the next generation of directors who have to start in a relatively difficult economic situation, and have to make cinema which will be meaningful without just having to compete with making it bigger and more Hollywoodian. I'm grateful to those two anonymous figures!

Amos Gitai: Yeah. I think that we have to try to do a few things at the same time when we make a film. Which is complicated but necessary. So we have to create a narrative, or a story or a thematic that we would like to evoke, but we also have to innovate in the form. In my mind, cinema is really going in a very unpleasant direction, that is fighting again and again to make more and more spectacular and violent, and we have to go to simplicity. We have to speak about understatement, we have to go back to some really basic ingredients from the beginning of performance, and work with it. That's also a suggestion for the next generation of directors who have to start in a relatively difficult economic situation, and have to make cinema which will be meaningful without just having to compete with making it bigger and more Hollywoodian. I'm grateful to those two anonymous figures!

Where did you film Tsili, which is meant to take place in the South of the Ukraine during World War II?

Amos Gitai: Some of it I filmed in the Galilee. Because I like my crews over there, they are very elastic.

It looks like the woods outside Nazareth...

Amos Gitai: The Carmel more than Nazareth. The northern Galilee. And because this is the magic of cinema, we can shoot wherever we can produce good work, we're not obliged to some naturalistic attitude. It could be anywhere.

In the haunting violin scene, the elders, are they Holocaust survivors?

Amos Gitai: They are, and in a way sometime when I do films I like to articulate things verbally, but sometimes I understand only retroactively what I did. To be frank with you.

I'm glad to hear you say that, so I feel it's OK to have a little more time also to understand some things in Tsili!

Amos Gitai: Absolutely! In a way when Tsili, Sara Adler, says "I want you to come back Marek," when she's whispering, in a way it's like the flutist of Hamelin who with his music will bring some element of humanity back, so these figures half hallucinating, half real will reemerge. These survivors.

I'm not asking you political questions, because I agree with you, from our talk about Words with Gods the other day, that politics should be left to the politicians. But from a human point of view, is there a way to talk, to have a conversation about Israel and Palestine?

Amos Gitai: Difficult. Because there is a lot of harm which was done, and continuous to being done, and I think that the people in power in this region don't care that they will destroy, burn every bridge possible and incite one against another -- they don't care. They're completely obsessed, each one with their ethnocentric truth and they will go to hell with that. And they will lead a lot of other people... I think that's difficult, I'm saying difficult I'm not saying impossible, but it's a bad moment. Hopefully we'll get out of it but it's a bad moment.

Would you say you're an optimist?

Amos Gitai: In the long run, I'm an optimist. We're sitting in this beautiful Venice but lets not forget that just a few days ago Europe marked a hundred years to the First World War. And the two big world wars killed tens of millions in Europe. This very enlightened continent between Velasquez and Beethoven and Goethe and these very enlightened people, the Europeans, who think they are the most enlightened on the planet were the biggest butchers, killed millions, burned the entire continent in two awful world wars. Just to reach the simple understanding that they can negotiate agreements and not start a war and kill every time they disagree. So I say often to Europeans, the Middle East is in a bloody and aggressive conflict but eventually, and I hope sooner rather than later, people will come to the understanding that they have to be a moderate, that they have to find a place for all, that they have to stop ethnic cleansing, that we need Christian communities in Iraq, that you cannot displace three million people in Syria...

Is there hope that cinema can help bridge the divide?

Amos Gitai: Cinema is always surprising. This morning I met a great Iranian distributor who loved the film.

Is Tsili going to play in Iran?

Amos Gitai: (chuckling) I don't know...

Could Amos Gitai do more for political understanding than all the politicians put together?

Amos Gitai: I think it is this "lieu de rencontre" Venice, and great because of that. Once I got a surprise, I was in Delhi and they gave me in the [Osian] Asia and Arab festival the big prize for my work. And there were twelve Iranian directors who saw several of my films in Tehran on DVD or whatever, so I think this is the positive aspect of our age, we can cross borders. But we are not so many.

When we try to have a film be an ambassador of peace, like your Ana Arabia which was in Venice last year, are we preaching to the choir? Meaning only people like you, who are already enlightened, will be learning something, when it should be a larger collective experience?

Amos Gitai: Should be but then we are dependent on modes of distribution that are being held, for the time being, not necessarily by the good guys, because that's not even political, it's about money. So, difficult.

They'll distribute Transformer before they'll distribute Tsili!

Amos Gitai: Ana Arabia was just released in Paris and got a lot of reactions, and even more interesting started with 17 screens, then went to 23, then it went to 34 and this week it's 47 screens. So it's kind of the opposite tendency... It's teaching in some way, going back to what those two gentlemen were saying. You know, culture, and this is really all along history, has always been an affair of the minority.

What makes a French audience so much more enlightened than any other audience? That Ana Arabia opens on a few screens, and then becomes a movement from there?

Amos Gitai: I think it's really not about the people. I think people are intelligent or not intelligent if they're in France, in India, in Iran, in Israel, in Palestine in whatever. I think it's what you can expose them to and what is the mechanism that is exposing and also I think that the French have been investing many years in educating people to be open to different forms of cinema. They're not doing so well today but still their slide is from a higher point of departure.

Is it an education then, do we need to educate audiences?

Amos Gitai: It is a necessity to keep people open minded about other forms. This is even more about forms than about a subject or even the politics. I grew up in Haifa, a small town in the north of Israel, when I was a teenager they just showed the normal classics, Bergman, Fellini, and so on. But it was really a joy to discover Pasolini or Glauber Rocha, Ghatak or Satyajit Ray. I think it's a great experience but you need the occasion to do it. Also I think beyond that it's very personal, because it's a complicated thing -- you need to be patient and impatient at the same time. It took me quite some years before I became a filmmaker. I only studied architecture and I studied it for over nine years. From my diploma in Israel to my PhD in Berkeley. I didn't feel particular pressure to succeed instantaneously, and I think this is good because you have time to research, to experiment... I think that the pressure on this generation to succeed immediately it is disastrous. You need to cultivate...

Succeed immediately and publicly -- everything has to be shared on Twitter and Facebook.

Amos Gitai: And you even lose the pleasure. The pleasure is essential.

If you could live anywhere in the world, where would you live?

Amos Gitai: At this point I would try to live in several places. I think it's difficult because the planet is in trouble. In different ways and different manners so you keep being curious and try to discover things and I think when you're not, it's time to stop anyway.

So where are you going to explore next?

Amos Gitai: Because I want to do this project on the killing of [Yitzhak] Rabin -- next year it's 20 years since the murder of Rabin -- I'll have to do research and meanwhile I have to go to North America and to Mexico and then, who knows...

Images courtesy of Film Press Plus, used with permission.