Saving world heritage sites is one thing. Activating them as economic and social assets for the local community is another project altogether. Our team aims to go beyond those bounds of conservation per se. Coming from our relatively comfortable seat in the world, the impoverished regions where GHF works do not have access to the resources we have been privileged to acquire. This means scarce resources for basic education; science and site management skills go without saying.

The idea to implement our methodology, Preservation By Design, is an ambitious one -- and it takes years. When you see what happens with hundreds of sites around the world or hear news about dramatic discoveries, you get the sense that local communities are tingling with anticipation, hoping to benefit from them as soon as possible without the know-how of proper investment and partnership.

Our goal as we sweep into GHF's second decade is to make Community Development, one of the four pillars of Preservation by Design, more robust and replicable, which means we will have greater capacity to insure sustainable community development in our projects and repeat that capability at other sites.

Why? Having the community directly benefit from a resource that they protect and cultivate just as you would a crop or a precious natural area, has proven to the best strategy. In fact, at several of our project sites, we have both natural area reserves and a heritage site. It makes complete sense since World Heritage inscription covers three categories: Natural, Cultural, and Mixed, which also means that the architects of these heritage sites clearly understood what they were doing when they constructed these marvels.

Traditionally, we look at pretty straightforward ways of measuring community development: jobs, income. The simple, obvious answers for the benefit of heritage sites include things like how many local people are trained and employed; how many locals are working in the tourism and hospitality sector around the site; as well as the indirect benefits of these activities for local business, agriculture, and so forth.

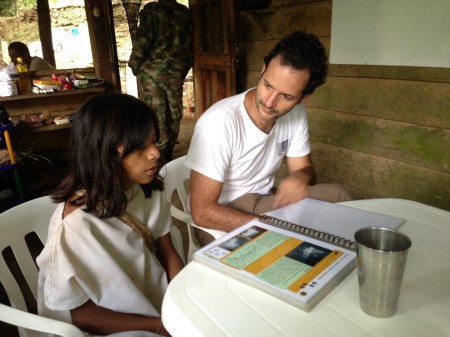

However, in recent years, the more expertise we develop in community development, the more we've come to realize that these numeric metrics are only the tip of the iceberg. This past summer, we built a health center on the trail to Ciudad Perdida, the 1000-year-old site in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta of Colombia. The project also just received a Global Vision Award from Travel & Leisure magazine for its conservation initiatives; that award is on my desk right now.

A couple of years ago, we also built a bridge over the Buritaca River, a dangerous crossing on the three-day trek route to Ciudad Perdida. This bridge was built after a traveler lost his life during a flash flood. Ostensibly, it initially served the tourist route, but it has quickly become a vital resource for the local people as it facilitates transportation in the same way the original stone staircases did a thousand years ago. Put together, the new health center will help if there is an emergency on the trail to anyone in need, but it ultimately serves the indigenous Kogi people who live there, own and operate homestays, help to ferry tourists up the trail, and are a primary target for community development.

So of course, we work to conserve the ancient earth platforms and stone surrounds, as well as the miles-long handmade stone staircases that connected the "cities" of the Tayrona, but we also build bridges, physically and metaphorically speaking. The health center, along with the installation of efficient stoves and graywater treatment systems in homestays are another example of this bridge-building movement, and they are a clear indication that we're breaking the boundaries of what 'heritage conservation' means.

Community development is not merely the equivalent of economic development, and neither is it numeric. These projects (bridge, health center) are infrastructural improvements that affect a whole variety of metrics and improve local life and livelihoods. When you properly approach community development as an integrated piece of heritage conservation -- as we do at Global Heritage Fund -- you realize that the goals and targets go well beyond numbers.

All that we've achieved over the last decade and continue to pursue in our community developments efforts were not born in one day. Community development is a process of improvement, and that can mean new and better jobs, more sources of income and other things that can be measured in numbers. But let's take one step forward: it also means improved access, additional (if not new) infrastructure and far more choices and options for the local population to choose from. These are generated opportunities that inherently create numeric achievements if you wish.

We walk them through the process of understanding heritage conservation from the ground up; from the world of yesterday to the present, so they can benefit from the opportunities that will present themselves tomorrow. Interestingly enough, this can also mean more natural conservation projects as I mentioned before, because conservation organizations today are moving more away from the wilderness model and looking to indigenous-managed landscape projects as a way to conserve the best of nature and culture in the most, naturally sustainable way.

For example, the MacArthur Foundation is investing in indigenous regions in the Andes and along the Mekong River, piloting projects that support native communities who live and farm these regions in a way that conserves their natural beauty and rhythms.

Sustainability means expending resources in a way that allows the next generation to enjoy and benefit from them as well. The cultural landscape as a whole, which is the world heritage site that comprises monuments, relics and treasures from an ancient civilization, while still serving as the home and core livelihood of an indigenous population -- is the most sustainable solution for both heritage and biodiversity.

We at GHF are honored and thankful to have the opportunity to work with the local communities around the world. It is their faith, willingness to learn, and open up to new ideas that makes these preservation projects possible. Ultimately, we don't just reconnect with our interlaced, shared history but with one another, a numeric value that is beyond measure.

I invite you to learn more about our other projects at: www.globalheritagefund.org.