The surprising rise of Donald Trump -- his remarkable polling results, the circus-like "what will he say next" campaign -- has captured massive attention. Trump's absence from the stage at the anti-climactic Voters First Forum in Manchester, New Hampshire made news. But such events have obscured a more important political reality. Rand Paul's campaign had planned for him -- not Trump - -to be the outlier pushing the party with new ideas, while making headlines and enemies. Though it is exceedingly early in the race, Paul is running out of opportunities.

Like Trump, Paul was always an unlikely contender for the GOP presidential nomination. But the decline of Paul's campaign has been astonishing. As Politico recently chronicled, it's close to ending practically before it started.

Recall that before Trump it was Paul who was briefly a media darling. Yes, he has been run over by the Trump juggernaut, as have most other GOP contenders, but unlike the rest of the field, Paul largely has himself to blame. He has reversed many of his major positions. And, at least so far, he has not prompted meaningful debate on any of the libertarian topics for which he is best known. But he is still trying. At the Forum in New Hampshire Paul pushed hard for "less government collection of private records from individuals." While campaigning in Iowa recently he declared that at the Republican Party presidential debate in Cleveland, Ohio on Thursday he would challenge his opponents whether they "want to always intervene in every civil war around the world." Going further, Paul argued "I'm the one candidate who does not want to blow up the world."

***

Given the limited range of views expressed at the highest levels of politics today, Paul's positions in recent years stand out. He is not a conformist. He seems principled. But eying the 2016 presidential election, Paul strayed from his libertarian foundations. He has felt the need to court the religious right on social issues, even ones like drug laws, which he once argued should be up to individual choice. In his push for the nomination -- despite his cloying photo op cutting the tax code with chainsaw -- he has not been as entertaining or offensive as Trump. And despite Paul's pandering efforts to engage the Koch brothers, among others, he has not been as effective with donors as Jeb Bush.

Where Paul had the most potential to generate consequential national debate is where he has recently given up the most territory: foreign policy and national security. It is on these grounds that he could still have a significant voice in the race. He might still advocate robust anti-interventionism, as he has in the past on debates over the role of the U.S. in Libya, Syria, and Afghanistan.

Where is the Rand Paul who filibustered dramatically against the Patriot Act and who opposed extensions of the national security state into the lives of every person in the United and many around the world?

A strategic, thoughtful Paul -- in the Senate and on the campaign trail -- could force both parties to better articulate when, where, and why the U.S. should intervene abroad. Instead, his recent speeches and interviews convey ham-handed efforts to keep up with the Trump publicity machine coupled with a newly discovered and shallow toughness about national defense and foreign policy. In Paul's April campaign announcement he asserted that the nation's "enemy is radical Islam," a trope he continues to employ. He also trots out the sop of cutting foreign aid to "quit building bridges in foreign countries [in order] to build some bridges at home." But such aid is less than 1 percent of the over $4 trillion federal budget.

Paul's professed aspiration when he entered the race was to pursue a foreign policy "wise enough to avoid unnecessary intervention." There is popular precedent for such a position. In the 1920s and 1930s -- the heyday of isolationism -- advocates did not call for complete economic or cultural separation from the world. Nevertheless, isolationists including "Irreconcilable" Senator William Borah (R-ID), argued against the "fetish of force" and militarism, famously rejected the League of Nations, and yet promoted instead peace activism and arms reduction, even the outlawing of war. These are the kinds of bold positions that would energize politics today.

Isolationist-oriented politicians historically have promoted a nationalist, non-interventionist position. They called for deep, sustained deliberations regarding any foreign interventions. The issue at stake for them, as it is ostensibly for Paul, was liberty and autonomy (variously defined, often vigorously debated).

Paul's forbears have been stalwart Republicans. From Borah to Herbert Hoover to Robert Taft (R-OH), the conservative wing of the GOP consistently advocated caution rather than hubris or expediency in U.S. relations with the world. They were not "weak" on national defense or communism. They fashioned themselves as nationalists and sought to establish strong defenses rather than interfere in other nations' politics. They perceived the Cold War as primarily an ideological and economic contest to be won by the U.S. through economic growth, soft power, and fiscal conservatism. As Paul's campaign collapses, he seems to lack the audacity to stick to these central tenets but is showing signs of what could be a transformative right-libertarian 2016 campaign.

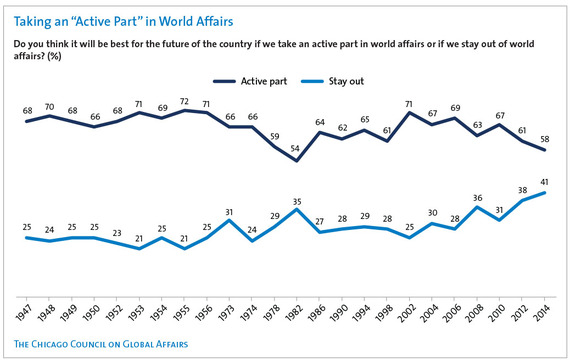

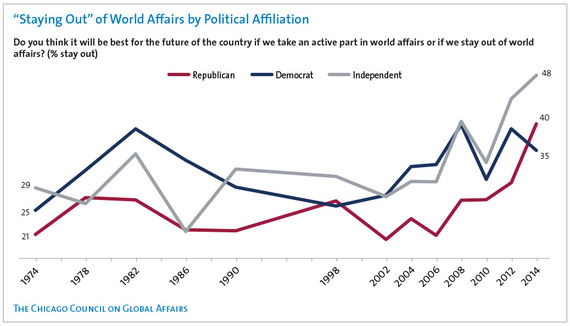

Recent polls suggest the potential appeal of such positions. Insights from the Pew Research Center over the past several years reveal that Americans continue to voice strong concerns about international organizations and a world seemingly "in crisis." They are profoundly wary of U.S. adventurism. A majority favor diplomacy over interventionism; they want the U.S. to "mind its own business internationally," modestly support drone policy, and do not favor "boots on the ground" in places like Yemen or Ukraine. And American public opinion is decidedly mixed regarding the feasibility and prospects for direct U.S. military invention in confronting the ISIS threat in Iraq and Syria (some worry about "going too far"; others worry about "not going far enough").

As the nation winds down commitments in Afghanistan after closing down combat operations in Iraq, poll after poll finds Americans want to be "active in the world" and repudiate the heinous acts of terrorists while giving the highest priority to pressing economic and political challenges at home. Given the U.S.'s widespread global entanglements, hundreds of military bases worldwide, and a complicated web of international trade connecting the world, no simple isolation is possible or desirable.

But an isolationist view opens up a wedge in American politics. As in the past, widening the parameters of political discourse forces all Americans to confront the limits of U.S. power abroad. History demonstrates that anti-interventionist and isolationist perspectives have not always been negative; in fact, they also have illuminated fallacies as well as arrogance, exposing fractures and embedded assumptions in foreign relations proposals and policies. Most of all, a circumspect view of U.S. foreign policy invites penetrating questions about American ideals and how they might be better embodied in reform at home regarding racial justice, higher education costs, or infrastructure needs, and abroad in terms of international commerce, drone policy, Russia's role in the Ukraine, ISIS, the drawdown in Afghanistan, nonproliferation issues with Iran and North Korea, and more.

An abiding wariness of overreach -- are the risks worth taking? -- is what American isolationists on the right -- and left -- have pushed for historically. Were Paul to champion this isolationist tradition, he could attract voters all along today's political spectrum, as seen in recent surveys by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, who are fed up with reflexive support for ever-increasing Pentagon budgets. If Rand Paul were a real isolationist -- a maverick thinker, not doctrinaire, to borrow the moniker once ascribed to John McCain -- rather than a crass political pragmatist he now seems to be, he might reject Trump, Bush, et al. He could build on a longstanding GOP tradition to present a coherent alternative foreign policy. Talking about foreign policy and the upcoming debate in Cleveland, Paul returned to his anti-interventionist roots. "I want to be known as the candidate who's not eager for war, who thinks war's the last resort." "When we fight," he remarked, "we fight to win, but much of our involvement has led to consequences that made us less safe. You'll see that come into sharp distinction [at the debate]."

It is not yet too late for such a stance. Though some see foreign policy heterodoxy as a liability within the GOP, it may well be a strength nationally (particularly with independents) and intellectually. A vigorous debate on foreign relations and national security, on the Iran nuclear accord, ISIS policy, NSA bulk data collection, and more, will make Paul stand out. By arguing for a more circumspect U.S. role in the world Paul could act as a countervailing force in politics beyond just the GOP debate and presidential field; by promoting debate, expanding policy options, Paul still has some room to generate new ideas that have the potential to help hold the nation back from rash interventionism and facile globalism (and help his candidacy at the same time).

For the 2016 campaign to offer choices, the nation could use a touch of isolationism, if only to expand policy options and open meaningful conversation. There is still a chance for Paul to make the upcoming debate about such ideas. He has so far squandered that opportunity. This may be Paul's last shot.