These are the questions people ask me most often: "Do you dream in English or in Spanish? What language do you feel most comfortable in? Do you feel more Venezuelan or American?"

The answer, Spanglish, the truth, los dos. I was born here, and I am proud of that. Y soy mas venezolana que la arepa, according to my friends.

I am bicultural.

This seems like a paradox. Little is known about how biculturals manage and negotiate their dual cultural identities. In my case, it has been a non-issue. I've lived biculturally in a very natural way where both cultures have existed as mostly complementary identities, with the clashes being minimal.

Here's why:

Firstly, I am this way as a direct correlation to how I was brought up. In my home, there were never any anti-American-being-from-somewhere-else-is-cooler sentiments, or the opposite. Yet my parents spoke only in Spanish to me at home and would not allow me to answer in English, as most kids do.

They had impeccable discipline.

I also spent all of my summers traveling all across Venezuela until I was 15, and sometimes, I would even go twice a year. I was lucky enough to have family always visiting and calling, which made it feel like they were close by. My mom also had very close Venezuelan friends who we treated as family, and with whom we kept traditions alive like making hallacas in Christmastime. So, Venezuelan culture was always extremely present, celebrated, and embraced. But so was American culture. I may have been that kid taking arepas to school for lunch, but I was also encouraged to do anything and everything "American," from pumpkin-picking, to Christmas-caroling, to Barney-watching. Any other non-Venezuelan culturally embedded activities us millennials were doing in the 90s, which we now associate with the best America had to offer, you can believe I was doing.

Basically, my parents trusted that I was going to be "Americanized" once in school, so they didn't teach me English at home, but they spoke it, so they could correct my homework or read stories in English to me before bed. They didn't impose on me to do what everyone else my age was doing, but they were able to connect with me on an "American level" while still emphasizing the "Venezuelan at home" philosophy. They didn't neglect American culture because they were immersed in it, too, without assimilating, but whilst conjoining.

I can't deny, though, that my environment has also played a huge role. I left San Jose, California when I was eight years old, during a time where Hispanics were deeply discriminated against in the area, seen as less than, and most importantly, "were all Mexican." I am sure that my experience would have been much different, and my upward social mobility would have been more difficult in a city like this. This was not the reality in South Florida. I spent the most formative years of my life there, from eight to 22. In the quilt, the melting pot, the eclectic environment of South Florida, everyone shines with their own hues.

My friends growing up were Jamaican-Chinese and all sorts of half this and quarter that. They were Haitian or Trinidadian and not just black. Being Spanish there means you're from Spain, not from Mexico. And each enclave of immigrants has its well represented pocket, allowing all ethnic identities to collide while maintaining their distinctness. This diversity is intrinsic to tolerance and acceptance, something I'm sure I would not have encountered in the same degree living somewhere else in the US. And this incredibly enriching environment gave me the safety net I needed to "rep" my ethnicity proudly while being American, too.

But also, I was deeply fortunate to be the child of parents who were professionals in this country. And that leads to my third point. My parent's socioeconomic background and educational attainment made it easier for both cultures to have equal worth in my world, and in theirs. My parent's careers, a TV reporter and newspaper columnist and a computer engineer, made it possible for them to compete in the white collar playing field where being a "minority" was more "forgivable" because intellect and talent were the great equalizers.

Unfortunately, as a country, we still treat blue-collar workers with little respect. For those who emigrate here without speaking the language and without access to the work force as a professional, discrimination from non-minorities is much easier to come by and much harder to combat.

Both my parents graduated from remarkable American institutions of higher learning, and were part of the wave of Hispanics deepening the dent in the glass ceiling that their predecessors (Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta, etc.) fought so strongly to create. Thanks to them, my parents and many other adults looking for opportunities here in the 80's were able to pursue the REAL American dream... the actualization of their career goals in a country not their own.

The new goal shifted from assimilation to integration. Johns could be called Juan again.

This I believe is what truly cemented my double-pride.

These three realities that I depict explain my very personal experience. Still, little is known about biculturals and how we operate or what allows us to grow up that way. But more attention will have to be paid to myself and my peers, especially to those of us of Hispanic descent.

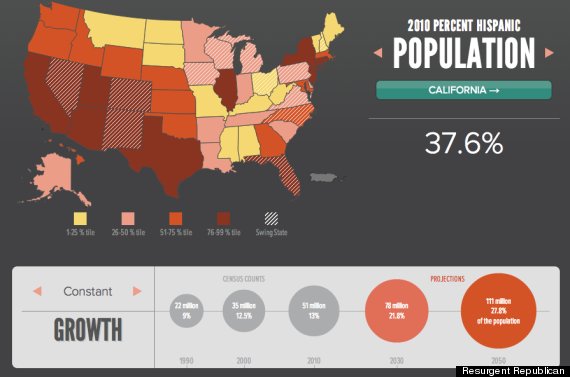

Because we will be a new majority.

(Source: Resurgent Republican.)

(Source: Resurgent Republican.)

The U.S. has finally started to catch on, and the media is starting to pay attention. Several years ago I came across an important report made by Alma DDB about the makeup of American Hispanics and how to label us. They called people like me "Fusionistas"and it is one of the best attempts to re-categorize the previously un-categorizable.

The article was so powerful, that I presume it was what inspired the new English language 24 hour news and entertainment channel launching this Fall dedicated to these biculturals: Fusion.

And its precursor, Mundo Fox, began to coin the idea that we biculturals are a new kind of American, with the slogan "Americano como tu."

Because of people like my mom, who proved that just because you speak with an accent, doesn't mean you think with an accent, the bi-cultural phenomenon is not so crazy to wrap your head around anymore.

The video below proves this point further. This would never have been possible even five years ago. An immigrant with broken English presenting a special on one of the most watched shows on basic cable? Believe it.

People like me and many others who consider themselves Hispanic biculturals are not only possible through upbringing and environment, but because of power in numbers. Latin Americans are finally receiving more respect here, and we are a serious economic force. In politics, Hispanics are all the rage (twins and Rubio, I'm looking at you). In business, people from the neighboring continent are strongly making their impression. In sports, music, entertainment, and academia, Hispanics with dual identity will become the new norm, and will define their culture, our culture, differently than before.

And I can't wait.