A group of U.S. forest ecologists, climate scientists and conservationists are calling out what they view as a “huge disconnect” between President Joe Biden’s rhetoric about the urgent need to combat deforestation and the policies he’s advancing back home.

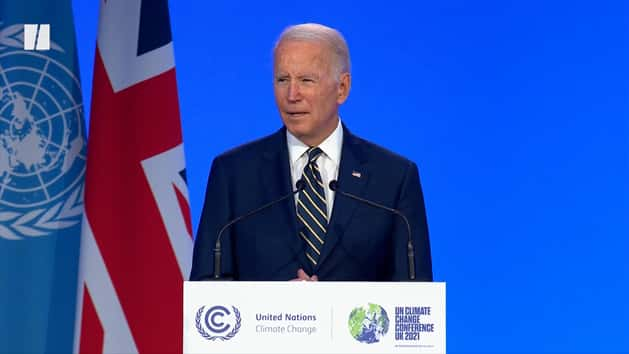

In remarks on his last day at COP26, the United Nations climate summit being held in Glasgow, Scotland, Biden touted the $550 billion in climate spending included in his Build Back Better plan making its way through Congress and applauded a new 100-country pledge to halt deforestation by the end of the decade.

“Preserving forests and other ecosystems can and should play an important role in meeting our ambitious climate goals as part of the net-zero emissions strategy we all have,” Biden said Tuesday. “The United States is going to lead by our example at home and support other forested nations and developing countries in setting and achieving ambitious action to conserve and restore these carbon sinks.”

His comments came a day after the White House released a 65-page long-term strategy for slashing greenhouse gas emissions that includes eyebrow-raising language about forest carbon removal: “Substantial forested lands, including large portions of our Western public lands, now have older forests which sequester less CO2 and are more vulnerable to natural disturbances.”

The line left “a lot of people going — pardon my French — ‘What the fuck!’” said Steve Pedery, conservation director at environmental organization Oregon Wild.

Pedery said the strategy document seems to float logging — specifically, cutting down mature stands of trees in order to plant younger ones — as a solution to climate change and climate-fueled wildfires.

“What’s next, resurrecting ‘clean coal’ and warning against the dangers of windmill cancer?” he said.

Old-growth forests sequester massive amounts of carbon in trees and soil, and scientists say protecting the few that remain intact will prove key to meeting climate and biodiversity targets.

Three forest scientists HuffPost interviewed — William Moomaw, professor emeritus of international environmental policy at Tufts University, Chad Hanson, forest ecologist at the John Muir Project’s Earth Island Institute, and Dominick DellaSala, chief scientist at forest advocacy group Wild Heritage — shared Pedery’s interpretation of the language.

The strategy document is “riddled with forestry science holes,” DellaSala said.

“We’ve got three ships passing in the night and we don’t have any skipper at the helm,” he added. “We’ve got a huge disconnect. ... What the heck is going on? It’s an embarrassment on a global stage, if people are able to read between the lines.”

Moomaw is a five-time lead author of Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports and considered the father of “proforestation,” which he defines as “growing forests to achieve their ecological potential for carbon accumulation and biodiversity.”

Moomaw said there’s a point at which growth and the rate of carbon storage peaks in a forest, usually in the midlife of the trees. This has led timber interests to argue ancient forests should be cut down and replaced with young trees. Moomaw called it “magical thinking.”

“Those younger trees, between now and 2050, will never have accumulated out of the atmosphere nearly as much carbon as the older trees would in that same growth time,” he said. “In other words, 30 years of growth of an older forest is going to remove more carbon out of the atmosphere by 2050 than planting new trees and letting them grow for 30 years.”

All three said Biden’s climate strategy document parrots that very industry talking point about replacing old trees with young ones. It’s a position that both ignores the initial carbon release from cutting down mature trees and operates on a timeline at odds with the emissions reductions scientists say are required to avoid catastrophic planetary warming.

“Any time you take trees out of the forests, you’re putting most of that carbon into the atmosphere,” DellaSala said.

“It’s all about the next few decades,” Hanson said. “The bottom line is we need to dramatically increase protection of existing forests — mature forests, old-growth forests, primary forests.”

As HuffPost previously reported, conservationists grew frustrated with the Biden administration early on over its lack of a strong commitment to halt logging of mature and old temperate forests in Alaska and the Pacific Northwest. But in July, Biden moved to reverse the Trump administration’s dismantling of protections and end large-scale logging of old-growth trees in Alaska’s Tongass National Forest, the world’s largest intact temperate rainforest.

After celebrating the Tongass decision as a sign that Biden is serious about using intact forests as a tool in the climate fight, many are once again feeling irked.

This week, Congress is expected to vote on the president’s bipartisan $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill and accompanying $1.75 trillion spending package. The two pieces of legislation include several provisions that some experts and advocates argue will increase logging on federal and private lands, undermine the bills’ massive clean energy investments, and worsen planetary warming.

As of Thursday, more than 200 climate scientists and forest ecologists have signed a letter calling for Biden and Congress to remove the provisions, including $14 billion in Build Back Better for “hazardous fuels reduction projects” on national forest lands and mandates in the infrastructure bill to reduce wildfire risk across 30 million acres of federal lands.

In the letter, which Moomaw, Hanson, DellaSala and others spearheaded, the group argues that the two bills’ forests provisions “are promoted as wildfire management and climate solutions measures, but commercial logging conducted under the guise of ‘thinning’ and ‘fuel reduction’ typically removes mature, fire-resistant trees that are needed for forest resilience.”

“We need the Administration and Congress to enact policies that will substantially reduce annual greenhouse gas emissions from logging, and from fossil fuels, and increase accumulation of carbon in our forests,” the letter reads. Other lead signatories include Beverly Law, a professor emeritus at Oregon State University and an expert on the forest carbon cycle, and William Ripple, a climate scientist and professor of ecology at Oregon State.

The White House did not immediately respond to HuffPost’s request for comment.

Hanson has plenty of critics. The Sacramento Bee reported last month about a series of scientific journal articles in which fire scientists criticized his opposition to thinning as a tool to reduce the risks of wildfires. One scientist, Susan Prichard, a fire ecologist at the University of Washington, went as far as to compare Hanson and his allies to climate change deniers. Hanson published a rebuttal of what he called “a heavily slanted article” and “attacks by Forest Service-funded scientists.”

Environmentalists are also not united on the idea that Biden’s Build Back Better plan would negatively impact America’s forests. In an interview with Vox, Collin O’Mara, CEO of the National Wildlife Federation, called the bill “the most significant investment ever in our national forests” and “an astonishingly big deal.”

As part of the new COP26 initiative, Biden said the U.S. would spend up to $9 billion toward the international effort to end deforestation and safeguard forest ecosystems. The funding would have to be approved by Congress, and House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer (D-Md.) has already introduced legislation to establish a $9 billion trust fund.

More than 100 nations representing 85% of the world’s forests signed on to the pact. But there are plenty of reasons to be skeptical about whether it will lead to real change. The New York Declaration on Forests, enacted at the U.N. climate conference in 2014, set a goal of cutting deforestation in half by 2020 and ending it altogether by 2030. Instead, deforestation has continued to soar.

The world loses an estimated 27 football fields of trees to deforestation every minute.

Back in April, dozens of environmental groups, including the National Resources Defense Council and Earthjustice, called on the Biden administration to impose a moratorium on all old-growth logging in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska and to make the protection of carbon-rich forests a central part of its push during COP26. More than 120 green groups renewed those calls in an Oct. 28 letter to the White House.

“It is not enough to simply pressure developing countries on older forest and rainforest protections — the U.S. must take meaningful action to conserve and restore carbon-rich forests and trees across all our forest types here at home,” the organizations wrote last week.