It can be hard to grasp all the details of Section 716, the Senate provision that would force big banks to spin off their swap desks, but the principle isn't that complicated: Banks that get access to discounted money from the Federal Reserve, or federally-guaranteed deposit insurance, shouldn't be able to gamble with them. And the four huge institutions that dominate the derivatives market shouldn't use the implicit guarantee of a taxpayer bailout as a license to act recklessly. Instead they should use that money, and that guarantee, to lend to the businesses that can get our economy moving again.

In this new, inverted political world, the "progressive" position is actually conservative, as in the dictionary definition of "conservative": "Favoring traditional views and values; tending to oppose change." Section 716 is a return to the old way of doing business. In the old days, banks got low-interest money from the Fed and lent it at somewhat higher rates. They earned the difference by assuming the risk of default and by lending the money wisely. The Fed "discount window" was never supposed to be a betting window, and the Federal Reserve chair wasn't supposed to be underwriting bets. Banks weren't gamblers, they were responsible lenders who knew their borrowers. (Think Jimmy Stewart in "It's a Wonderful Life.")

The old left/right idea of "business" vs. "populism" doesn't really apply when it comes to this aspect of financial reform. The question is now, will Congress be pro-business ... or pro-big bank? With provisions like Section 716 you can be one or the other, but not both. If they're pro-business, which ironically has become the "populist" position, they'll insist that the big banks stop gambling with the public's money and start lending it to the businesses that account for most new jobs in this country.

As the Americans for Financial Reform website explains, Section 716 "will require, inter alia, the five largest swaps dealer banks to sever their swaps desks from the bank holding corporate structure." They can own subsidiaries that handle swaps - the sort of derivatives that wrecked the economy last time around - but they have to keep them separate from banking operations.

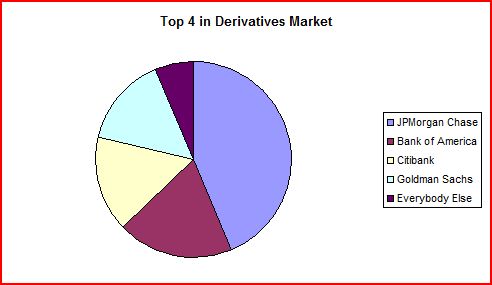

The top five banks dominate the derivatives market, with the top four holding the lion's share. We developed this chart for an earlier post, based on the overall derivatives market:

The trading operations for these four banks didn't lose money for even a single day last quarter. This round of financial reform won't break up this cartel or end the rigged casino - but Section 716 would ensure that they we don't stake them the money.

As an example, how did Goldman Sachs' trading arm do? According to their own earnings statement, Goldman's Trading and Principal Investments group earned $10.25 billion in the first quarter of 2010, up 43% from a year earlier and 60% higher than its earnings in the previous quarter. Data are harder to break out for the other banks, but we can rest assured they did well.

Nobody who's winning big in the casino wants to bother lending money to entrepreneurs. From April through October of 2009, overall bank lending to small businesses dropped by $11.6 billion. The Treasury Department's monthly report on bank lending indicated a further drop in January. Renewals of business accounts decreased 47% that month while total new loan commitments decreased 20%.

Treasury responded decisively to its own January figures - by deciding it wasn't going to release any more of these monthly reports. Not meaningful, they said.

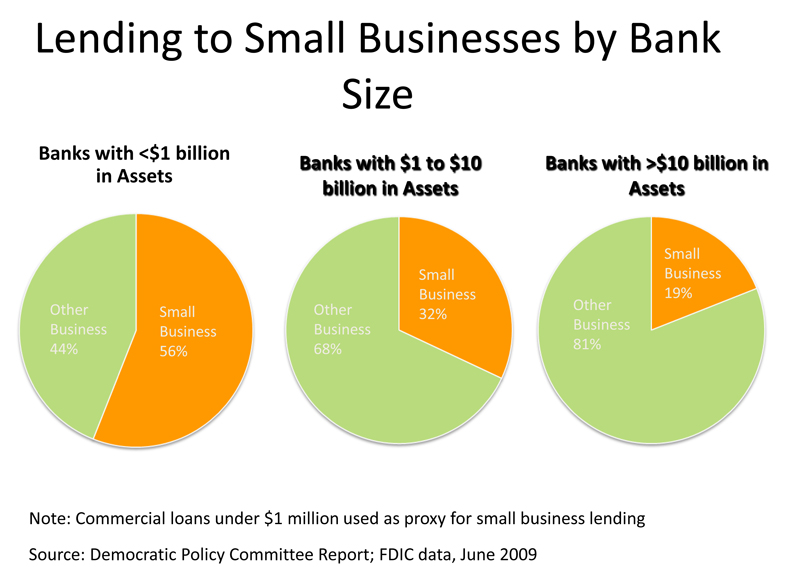

Our four big derivative speculators were part of the overall freeze out on business lending in 2009, as this chart shows:

And, as CNN reported, the 22 banks that got the most help from the American taxpayer slashed their small business lending by $10.4 million.

The trend had begun a year earlier, at least for the mid-sized loans that often support new hiring. An SBA study shows that loans in the critical $100,000-$1,000,000 range, typically provided to those mid-ranged businesses that drive job growth, were already down 23.3 percent from June 2007 to June 2008. While demand also affects loan volume, the larger trends toward tight credit suggest an overall pattern.

Which banks are the least likely to lend money to smaller businesses? You guessed it: the large ones:

Big follows big, apparently. During the same period that lending plunged for mid-sized business (2007-2008), the same SBA study showed that volume on business loans of more than a million dollars continued to soar. These larger loans grew 12.2 percent during that period, after increasing by more than 11 percent the year before.

Owning a small business has becoming an increasingly difficult way to make money in this country. A Small Business Administration study concluded that households owning a small business (as opposed to several businesses) fell behind in the last couple of decades, unable to grow as quickly as other types of households. The study adds that these businesses "may be adversely affected by further concentration in commercial banking and less relationship lending at the local level." In other words, mega-banks don't know their borrowers and don't help them start businesses. (There's Jimmy Stewart again ...)

Make no mistake: Section 716 doesn't end "too big to fail." The Senate already killed that possibility when it voted down the Brown/Kaufman SAFE Act. But it would force banks to create and fund subsidiaries to handle derivatives, preventing them from co-mingling speculative capital with money they've been lent for genuine banking purposes. It would prevent the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) from providing guarantees for dealing and trading derivatives. And now that Section 716's been changed to meet Paul Volcker's concerns, chances of its passage look even better.

The Section 716 debate has become a proxy fight that pits Main Street American businesses - the engines of economic growth - against the megabank lenders who have been using publicly provided discounts to make out like bandits.

______________________________

Richard (RJ) Eskow, a consultant and writer (and former insurance/finance executive), is a Senior Fellow with the Campaign for America's Future. This post was produced as part of the Curbing Wall Street project. Richard also blogs at A Night Light.

He can be reached at "rjeskow@ourfuture.org."

Website: Eskow and Associates