This blog is from a series of posts following the Down the Colorado expedition.

In the morning, we slide our kayaks into the Colorado River and paddle towards the rapids of Gore Canyon. The surface of river, slowly meandering its way through flat ranch lands near the town of Kremmling, is alive in the early light. A few strands of spiderweb fly by on an otherwise undetectable breeze. The bows of our boats cut through the water quietly.

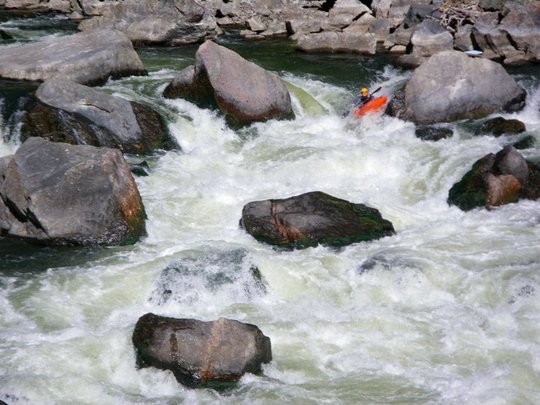

After nearly two weeks spent following the Colorado River hiking on mountain trails, padding across reservoirs, and floating down the shallow, mostly flat upper river, we're looking forward to some whitewater. Last night we reached the confluence with the Blue River and the Colorado's flow was more than doubled. And now we're headed towards the first Class IV-V rapids of the trip, the 8-mile stretch that several locals referred to as "Big Gore Canyon." Gore is one of the few whitewater sections in the state of Colorado that has enough water to float a boat during this severe drought year, and we meet kayakers coming all the way from Denver and Durango. Of our four expedition members, three of us are paddling kayaks and have been down Gore many times before. Carson McMurray, the forth crewmember, is new to river running. He's piloting a small inflatable packraft and plans to hike around the bigger rapids.

All of us are a little anxious, but the Colorado, even with its increased volume, is in no rush to reach the notch in the mountains that marks the beginning of the canyon. It moves back and forth in lazy loops, flowing over sandbars, past flocks of pelicans and between more fragments of web. One strand in particular catches my eye. It's moving directly towards my boat as lazily as the river is moving towards the Gore Range. As it floats closer, I see there is something attached to the end -- an airborne spider dangling from its homemade sail of silk. It's losing altitude quickly and headed for the water a few feet ahead my kayak. I instinctively take a few strokes towards it, thinking I'll catch it on my bow and save it from a watery grave. But I miscalculate and it sails right over me, landing on the surface of the river. Amazingly, the web does not sink onto the water but remains in the air still being slowly propelled by the wind. The spider, seemingly unperturbed, skates across the surface of the water with its paraglider-turned-kite doing the work.

I watch the spider cruise away until I can no longer make it out against the grassy riverbank. Then I paddle on. I didn't come here expecting to watch spiders, and as the current finally begins to quicken my thoughts move elsewhere. The low grass banks turn to rugged rock walls towering 1,000 feet above us and soon the rapids begin.

A few hours later we emerge from the other end of the canyon, our hair still dripping from under our helmets and the adrenaline subsiding. Since we launched this morning, the three of us in kayaks have found mostly what was expected: rapids forcing us to maneuver quickly between offset boulders, a few waterfall-like drops where our boats catch several feet of freefall before landing in the churning pockets of foam below, plus a few missed paddle strokes, several moments of terror, and a whole lot of hootin' and hollerin'.

For the packrafter, Carson, it may have been a little less fun but more action packed. After piloting several Class III rapids (no small feat for a river novice in craft designed for crossing flatwater in the backcountry), Carson made more than one mad sprint through the train tunnels along the riverbank. He found it the easier than portaging the larger rapids over steep rocky slopes, though he had to pray the roar of the river wouldn't be enough to muffle the roar of an oncoming freight train. We all emerge unscathed. Even after all the excitement, even after weeks of hyping up Gore, the moment that stands out most clearly from the day is the sailing spider, bolder in my memory than any of the Gore's other rewards.

I think this is a fairly common experience for people who participate in any sport labeled as "outdoor recreation." Whatever it is that draws people to our public lands -- be it a scenic mountain trail, a prime fishing hole, a slope of fresh snow, or a series of rapids -- isn't always what stays with us when we return to civilization. Sometimes it's the unexpected encounters with a living landscape that bring us back out the next time and not to the trophy catch or finding the best powder turns. Sometimes the sport may serve more as a way to discover that sudden revelation of color, a coyote's gaze, some remarkable geometry of tree branches, or a floating arachnid than anything else. But for the addicted outdoors enthusiast, their sport of choice just happens to be the most interesting way to arrive at that exceptional moment that cannot be planned or pursued. Playing out of doors and away from asphalt differs from recreating in an amusement park or a basketball court in that it takes us away from our homes and business. It takes us beyond the right-angled world we attempt to make useful and allows us to visit, however briefly, the more-than-human world living and dying beyond our control.

For more information on the trip visit www.downthecolorado.org.