To most watching last week's debate between creationist Ken Ham and science educator Bill Nye, it was a battle between religion and science. But to creationists -- a group which not too long ago included me -- the debate was something else entirely: a battle over the very meaning of science itself.

At the Creation Museum in Petersburg, Kentucky, Ken Ham used his interpretation of Genesis to argue against evolution. He claims all animals on Earth descended from around 10,000 distinct, divinely created animal kinds, splitting apart through minor adaptations into the more than 10 million species alive today. He argued that the universe is less than seven thousand years old and that Earth's surface was destroyed four thousand years ago in a cataclysmic global flood.

Ken Ham is not alone. Though I'm no longer a creationist, there are many people I still know and respect who agree with these beliefs deeply. Young Earth Creationism only emerged to begin disputing mainstream geology, archeology, and astronomy in the early 1960s, but today one-third of Americans believe earth is only thousands of years old, with even more doubting evolutionary common descent. Government-funded schools in 13 different states teach forms of creationism. Ham's views may seem unbelievable to many, but he is the representative of a sincere and passionate movement.

As the representative of mainstream science, Bill Nye took a shotgun approach to the debate, bringing up multiple lines of evidence demonstrating the ideas creationists most often dispute. He brought a piece of rock from the strata that run directly underneath the Creation Museum, asking how the football-field-deep limestone bed -- filled with alternating layers of microscopic fossil creatures that could have only lived and died in calm, shallow water -- could have formed in a year-long global flood. He showed photos of annually-deposited ice cores 680,000 layers thick. He showed how the worldwide distribution of fossils is consistent with animals evolving in the same regions they inhabit today, rather than migrating out from the Middle East in pairs after a global flood. He pointed out that fossils only exist in the layers evolution predicts, that the stars are too far away for their light to have reached Earth in only 6000 years, and that the atomic clocks of radiometric dating are consistent and reliable.

But creationism isn't successful because it ignores the evidence. It doesn't. Creationism is successful because it consistently finds ways to reinterpret the evidence to fit its presuppositions. Throughout the debate, Ken Ham insistently repeated that although scientific research in the present is testable and repeatable, scientific inquiry into the past -- what he calls "historical science" -- can never be proven and is always open to interpretation. This belief may seem odd to many, but for people who grew up with creationism, it makes perfect sense.

As a creationist, I believed investigation of the past followed different rules than the sort of everyday science that builds bridges and cellphones and spaceships. Looking at the past, I thought, required a fundamental set of assumptions about how the evidence ought to be interpreted. Evolution and long ages came from assuming atheistic "uniformitarianism" -- the idea that everything we see today had to be the result of slow and gradual processes. Creation and a flood and a young earth, on the other hand, followed naturally as long as one's presuppositions allowed the possibility of a Creator. In this way, I saw both sides as philosophical models. That's why Ken Ham kept insisting over and over that science is being "hijacked" by "the religion of secularism"; this accusation of pervasive bias is the only defense creationism has against the evidence.

No matter how obvious the evidence seemed, I always assumed it was just a matter of interpretation. But I was mistaken, and not just about the facts themselves. I was mistaken about how science actually works.

Bill Nye's most effective argument was not the evidence he brought, but his understanding and explanation of the scientific method. His examples demonstrated that science -- whether studying the present or the past -- depends not on assumptions or interpretations but on a foundation of testable predictions. Nye showed models aren't just assumed to be true; they're tested on the basis of the predictions they make.

His best example of this process came when he explained the evidence for the Big Bang. Astronomer Edwin Hubble first obtained proof the universe was expanding in 1929. Different astronomers proposed different explanations for this, but the most revolutionary proposal was that the universe had been expanding for billions of years after starting as a ball of hot gas.

According to the creationist view of mainstream science, astronomers would have simply assumed the cosmic expansion theory -- known as the Big Bang -- right then and there. But that's not what they did. Instead, the scientists pursuing the Big Bang model looked for a prediction they could test. They realized that if the universe had begun as a rapidly expanding ball of hot gas 14 billion years ago, the heat from that gas should still be visible as a faint glow coming from every direction, far beyond our galaxy. In 1948, they used their theoretical calculations to predict the exact color and exact temperature of the glow they expected to find.

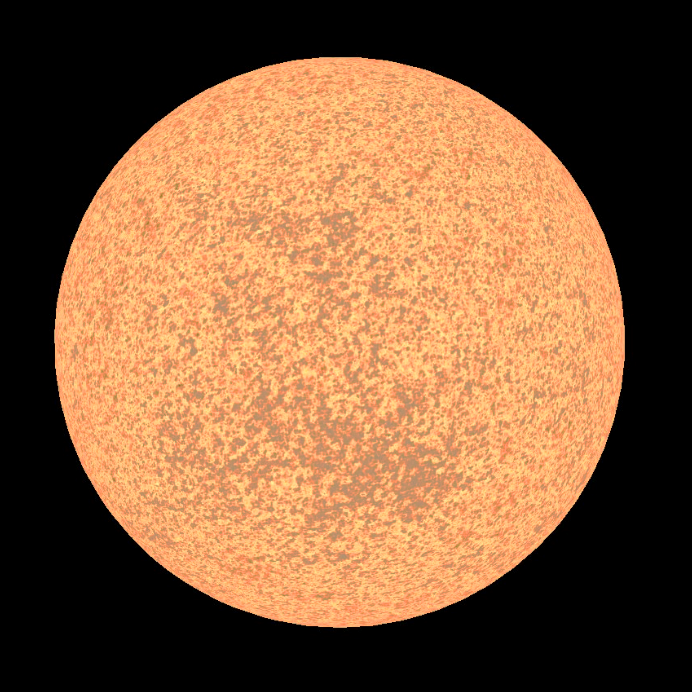

Bill Nye explained that in 1964, astronomers in New Jersey detected a faint microwave glow -- initially nothing more than a "hiss" on their radiotelescope -- coming from the very edge of the visible universe, exactly as the Big Bang Theory predicted. The glow was just three degrees warmer than empty space, and exactly the same color as calculations 24 years earlier had said it would be. Today, spacecraft have imaged this glow -- referred to in cosmology as the Cosmic Microwave Background, or CMB -- coming from every corner of the sky, clearly enough to produce this radiophotograph of the hot, dense universe almost 14 thousand million years ago.

2013 composite radiophotograph from the Planck spacecraft, courtesy NASA. Public domain with attribution. Image has been overlayed onto the surface of a sphere and digitally tinted by the author to match a 3000K blackbody radiation spectrum.

This, Nye explained with visible pride, is how science really works. There are no untestable presuppositions, no atheistic assumptions. Science gives us the tools to probe the mysteries of the universe and to confirm whether or not we're on the right track. It doesn't rule out a creator; it just provides us with information about the universe. Science doesn't care whether I am a Christian or an agnostic, a liberal or a conservative; it only demands testable predictions and empirical evidence.

That is how Bill Nye won the debate. Over and over, he asked Ken Ham for specific pieces of evidence that would be predicted by creationism. "We would need just one piece of evidence," he said in his closing statement. "We would need the fossil that swam from one layer to another, we would need evidence that the universe is not expanding, we would need evidence that the stars appear to be far away but are not.

"We would need evidence that rock layers could somehow form in just 4000 years ... we would need evidence that somehow you can reset atomic clocks and keep neutrons from becoming protons. Bring on any of those things and you would change me immediately."

Nye's demand for specific evidence did more than merely challenge creationism. It demonstrated that the foundational basis of Ken Ham's ideas -- that mainstream science is somehow closed off to the evidence through atheistic assumptions -- is simply wrong. Science doesn't depend on naturalistic presuppositions; it depends on predictions and evidence, and Bill Nye couldn't have made this any more clear.

Some will still remain convinced by Ken Ham's steadfast faith in his interpretation of the Bible. But many will see Nye's willingness to examine the evidence and realize -- like I eventually did -- that science isn't founded on atheism at all; it's simply the way we learn about our universe, regardless of what religion we do or don't espouse. Bill Nye set out to educate people, and that's exactly what he did.