When I entered the Peace Corps and headed to Malawi after college, I was head-over-heels in love with a girlfriend back home. Before I even got on the plane to fly overseas, I was missing her terribly. I knew that the only way to cope would be writing her letters and talking to my fellow volunteers about the significant others they had also left back in the States.

The first time I realized that speaking about my relationship might be a problem was when I was in my homestay for a month during training. I had a photo of my girlfriend and me displayed in my hut, and my language trainer asked to see it.

"Oh, is that your boyfriend?" she asked me. "He's very cute!"

My girlfriend -- let's call her Molly -- had short, cropped hair in the picture, and it was taken at my senior formal, so she was also wearing a suit. She could have definitely come across as male to some.

I fumbled for an answer. "Uh, well, that's my chibwenzi," I responded. In Chichewa, Malawi's native tongue, "chibwenzi" means both "boyfriend" and "girlfriend."

My language trainer smiled, and that was that -- at least for her. My cheeks reddened, and an overwhelming feeling of guilt overtook me. I had lied to myself about my sexuality for so many years; to be back in the closet was painful.

In Malawi, homosexuality is illegal. The country's penal code has a section for "unnatural offences," stipulating that anyone who "has carnal knowledge of any person against the order of nature ... shall be guilty of a felony and shall be liable to imprisonment for fourteen years, with or without corporal punishment." This is also true of anyone found to even "attempt to commit unnatural offences."

Despite the fact that, as a volunteer with the United States Peace Corps, I likely would have been protected from such laws, I knew that the Malawians in my homestay village, as well as those in the village I was ultimately stationed in, would look at me differently if they knew about my girlfriend. I also knew that that knowledge might even preclude me from helping them in any way, which was the entire reason I was a volunteer to begin with.

Therefore, I kept my mouth shut. I referred to Molly as nothing but my "chibwenzi" when asked, avoiding the use of gender-specific pronouns when I could. When I couldn't, I simply referred to her as "Mo," a gender-neutral nickname that I had never once actually used prior to setting foot in Malawi.

This particular aspect of my time with the Peace Corps sticks with me when I think back on my days there. Back in November 2012, Malawi placed a short-lived moratorium on the laws criminalizing same-sex relationships and behavior. Unfortunately, days later, the Malawian Minister of Justice denied this suspension. The law remains in place.

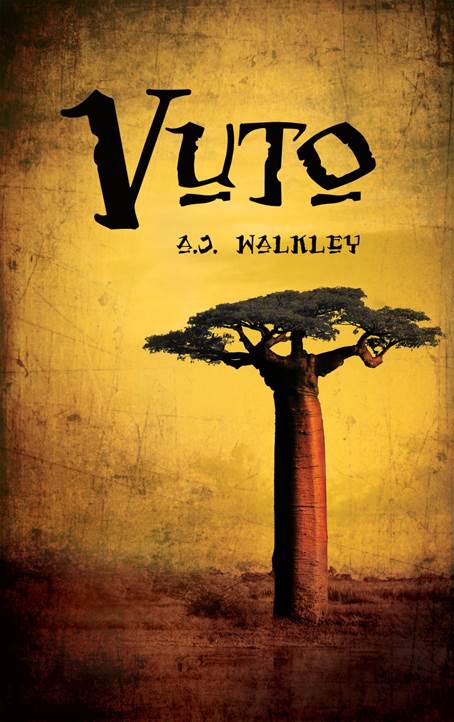

I recently wrote a book inspired by my Malawian experience, Vuto, which means "trouble" or "problem" in Chichewa. It not only references the sexuality conundrum but brings up cultural differences between the West and Africa that specifically affect women. The primary custom I focus on in this novel is a tradition that prohibits fathers from acknowledging a new child until the child has survived for two weeks after birth; if the child dies before that two-week mark, the mother and women mourn the child alone. I have a Kickstarter project up and running to fund Vuto's publication in hopes of raising awareness about such customs, which seem so strange and antiquated to the Western world.