It's been nearly 60 years since the first black woman obtained an architecture license in the U.S.

And recently there has been a slow, though steady, rise in black enrollment in college design and arts degree programs, and a sharp uptick in the number of minority architects.

Yet African Americans today remain vastly underemployed, not only in architecture but in all the interior and graphic design professions as well.

The reasons remain somewhat elusive as the issue continues to bedevil magazines and trade shows, design firms and baccalaureate arts programs.

Some experts blame a pipeline effect that stems from underfunded art programs at the high school level. Others say it's a case of black designers simply not being invited to the table. What most insiders agree on, however, is that diversity in design makes for a much richer experience, both for the design community and for the consuming public.

"For the design fields to be as underrepresented as they are means that the quality and relevance of the work to a broad and diverse population is really just problematic," says Joel Towers, executive dean of Parsons The New School for Design in New York City. "You don't have the richness of ideas and possibilities that are presented by having multiple perspectives going into the work.

"The problem has been talked about publicly since 1954, when Norma Merrick Sklarek became the first black female to receive an architecture license in the United States. More than a decade later in 1968, the problem prompted National Urban League president Whitney Young's famous call to action at the American Institute of Architects' National Convention.

According to the National Association of Schools of Art and Design, about 103,000 students enrolled in art/design-focused bachelor of fine arts programs across the country in the fall of 2010. The same semester, nearly 3,600 black non-Hispanic students enrolled.

While NASAD doesn't track the degrees those students attained and although not every design school in the country reports in, their data does suggest a jump in overall design school enrollment, from 72,000 in 2000 (2,300 of which were black non-Hispanic) to 84,000 in 2005, with 3,200 identifying as black.

It's still a far cry from the numbers of students enrolling in liberal arts programs and even further behind the curve when African Americans are factored in.

"If you look at higher education, you see that art and design in general are not drawing as large a population and as diverse a population from the high school level into the college level," Towers says. The problem, he believes, starts very early and lies in public schools' inability to keep up with art or design courses.

"So the first thing to get cut when school budgets are cut is art," he says, leaving colleges like his with a smaller, and certainly a less diverse, pool of talent to draw from.

Judy Nylen, director of career services at Pratt Institute in New York City agrees. "The decline of art programs at the high school level, as budgets are cut and math and science are pushed, means even less understanding of what is possible in creative fields," she says, referring to a long-standing belief that art and design are less viable career options than, say, medicine or law.

It's a notion that these institutions and others are fighting to dispel through weekend enrichment programs, like the Pre-College Preparation Scholarship Program at Parsons, which provides students with full scholarships, beginning in their sophomore years of high school. The program includes courses in fine arts, design and portfolio preparation, along with mentoring from students who've gone on to college.

In Philadelphia, the Charter School for Architecture and Design is tackling the notion in its own way, offering students 80 minutes of coursework each day centered on architecture and design.

Once barriers are broken in high school, the focus shifts to maintaining diversity at the college level and beyond.

WATCH:

For Towers and his staff, this means taking a hard look at the way their curriculum is constructed, how it's taught and, most importantly, the dominant narratives. "It's no surprise that when you tell the history of art and design, largely because it's been so under-represented in a lot of different ways, it can be a fairly alienating history. And if you choose to tell it from a particularly Western perspective, it's even more so," he says.

In Baltimore, Md., Carolyn Edlund and her colleagues at the Arts Business Institute are helping arts students focus on the skills required to run successful art-based businesses, something she says most art schools fail to provide, and skills that aren't inherent to creative types.

"A lot of right-brained, creative people have no business background, and they come up short, or they end up losing money or they go out of business because they don't know how to do it," Edlund said, detailing a series of workshops she recently taught in marketing, booth design, salesmanship, wholesaling and pricing.

At the Savannah College of Art and Design, architecture and interior design programs have a global focus that encourages students to study art and design from all ethnic perspectives, says Rebekah Adkins, a professor of interior design. "Many of our students' thesis work is culturally based."

Adkins points to a project at the school's Atlanta outpost, where African-American interior design master of fine arts candidate, Camilla Watson, is working with young residents of Vine City, Ga, a low-income urban community, to create an interior design scheme for a youth center. The hope is it will help bring awareness to social issues and create a space where residents can cultivate civic engagement.

In some cases, bloggers are stepping in to raise public awareness where the media has failed to note the accomplishments of black designers and architects.

Jeanine Hays says it was the lack of familiar faces which prompted her to leave her job as a policy attorney and delve into the world of blogging and product design. "The first thing I noticed when starting the blog is that there were very little people of color on the design blogs that were out there," she says. "There was nothing that spoke to me as a woman of color. It almost felt like I didn't exist."

That invisibility, she adds, can function as a roadblock to creativity among designers, and where her blog, Aphrochic, can come into play. "It was sort of like saying 'I'm here! I love the same things you love, but I also want to see things that look like me,'" Hays says, pointing to other bloggers who share in her mission. They include Melinda Lewis of Get + Togetha blog and Tina Shoulders, who embarked on a 28-day project showcasing designers of color a couple years back.

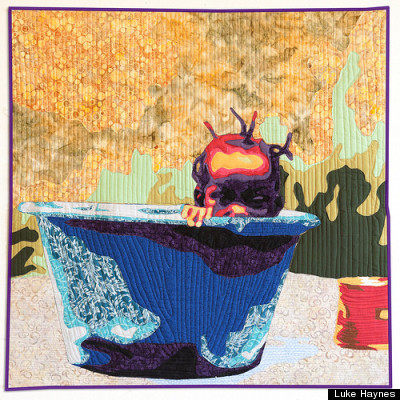

Even for Hays, however, it takes a concerted effort to give African-American design equal representation in her editorial mix. Sometimes it simply means looking for ethnic influences in the work white artists are creating, as she did in a post on quilt designer Luke Haynes.

The prospects for minority architects appear somewhat brighter.

In 2009, the American Institute of Architects reported a sharp rise in the number of minority licensed architects, from 11 percent to 18 percent, with a three percent increase in the number of minority partners/principles. Minorities now compose 19 percent of all architecture staff, it reports.

Easier access to licensing programs could be the cause. But designer Robin Wilson, whose firm was selected to design and manage the rebuilding of the private residence of Robert F. Kennedy Jr., which she documented in the book Kennedy Green House, says there's a historical context at play, too.

"Many people do not remember the historical fact that African Americans have been involved in building construction, design and architecture since the earliest days of America -- through slavery, plantations, housekeeping, and artisan skills. Until industrialization in the 1930s, when trade unions began to exclude blacks and formal certification began to be required, it was possible for blacks to hold jobs as mill workers, carpenters and iron workers.

Wilson points to Paul R. Williams (1884-1980) known as the "Architect to the Stars" for his work on LAX airport and the private residences of Frank Sinatra, Clark Gable and Cary Grant; Julian Abele (1881-1950) who was a leading, but often unrecognized, contributor to designs such as the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Harvard Widener Library and many private residences in Newport, R.I., and New York City; and more recently those who've shifted from structural to product design, including Andre Hudson of Hyundai, who led the redesign of the 2011 Sonata.

It's a list, she says, that has yet to be seen on the pages of a major design magazine, crediting instead bloggers like Pink Eggshell's Kimberly Ward for her 2011 list of the top 20 African-American interior designers.

"I don’t see design aesthetics as being ethnically based," says Newell Turner, editor-in-chief of House Beautiful magazine. "But I do think role models in any field open the door or expand the horizon for the next generation," he says.

"Some of the most successful African-American interior designers that come to mind are Daryl Carter, Sheila Bridges, Roderick Shade, and even Venus Williams," he says. "They are definitely known for their work and serve as inspiration to anyone thinking of entering the industry."