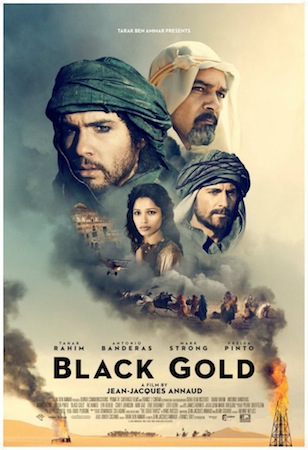

I had high expectations for Black Gold, the film that kicked off this year's Doha Tribeca Film Festival in its world premiere. After all, there was so much riding on it, the first big budget Arab blockbuster, a collaboration between major U.S. studios Warner Bros. and Universal with Tunisian visionary producer Tarak Ben Ammar's Quinta Communications and Qatar's own Doha Film Institute. A story about Arab protagonists, filmed entirely in MENA -- Qatar and Tunisia -- and finally chock full of subtext that could inspire the rest of the world on the heels of the recent Arab Spring revolutions, which coincidentally broke out in Tunisia while the film was being shot.

On a hot desert morning in Doha, I finally watched Black Gold, in the air conditioned comfort of a dark screening room with plush seats. Leaving aside the powerful story, the great acting and the important themes, I was delighted further by what the film represented to me, an aficionada of Arab cinema, and someone who dares to dream that cinema can and will one day unite our "us against them" world.

Black Gold is based on the 1957 book South of the Heart: A Novel of Modern Arabia by travel enthusiast and sometime race car driver Hans Ruesch, who was born in Naples of Swiss parents. It tells the story of two Emirs, Nesib and Amar, who come to agree to keep the strip of land that divides their countries, a no-man's-land called The Yellow Belt, neutral. In order to seal the deal, Nesib adops Amar's sons Auda and Saleeh as a guarantee that neither will ever be able to invade the other. When the boys are all grown up, an American shows up to tell Nesib that The Yellow Belt is blessed with oil, which naturally gets the Emir thinking of how much this would mean for his people. On the one side is the temperate, more spiritual Amar, who believes that "anything that can be bought has no value" while Nesib will go to any lengths to achieve his goal, which may not be so wrong after all. The stage is thus set for an epic battle, one that promises to change the viewer's idea of right and wrong with its welcomed shades of grey.

As the end credits rolled on, I felt myself in another world, one where I thought I could walk out of the film able to share the insight I had just acquired with my equally enchanted international colleagues, also there to cover DTFF. I admired the sensitivity of Annaud in capturing the daily struggles of the Arab world, where religion is always a factor in the way business is conducted and where wealth has been divided so irregularly among nations.

"What did you think of the movie?" A voice nearly jolted me out of my cozy dream state. The question had come from an Egyptian journalist who works for the Arabic radio division of a global TV network.

"I really loved it..." But before I could get my entire thought out, he interrupted me with a combination of disdain, contempt and scorn and the dreaded "O" word I have grown so accustomed to, as a non-Arab writing about films from the Middle East.

"It's pure Orientalism! So full of cliches. The last good film depicting Arab characters was Lawrence of Arabia. Since then, nothing has captured our spirit." I indulged his comments and company a bit longer, more out of being left speechless than any true professional grace on my part, and went on to press conferences, interviews and junkets of the day, still mulling over whether my colleague and I had actually watched the same film.

Sure, Antonio Banderas was one slight move away from his trademark overacting in the beginning scenes, while Freida Pinto may have underacted into meekness while trying to deliver the perfect royal 1930s Arab Muslim girl performance, but I clearly saw within Black Gold a film that could boldly create a bridge between two cultures, cultures that have built up nothing but mistrust for one another, until now. Not to mention, the three main performances by A Prophet phenomenon Tahar Rahim, the sultry, talented Mark Strong and charming voice of reason Riz Ahmed, who all stole the show and my heart.

Sure, Antonio Banderas was one slight move away from his trademark overacting in the beginning scenes, while Freida Pinto may have underacted into meekness while trying to deliver the perfect royal 1930s Arab Muslim girl performance, but I clearly saw within Black Gold a film that could boldly create a bridge between two cultures, cultures that have built up nothing but mistrust for one another, until now. Not to mention, the three main performances by A Prophet phenomenon Tahar Rahim, the sultry, talented Mark Strong and charming voice of reason Riz Ahmed, who all stole the show and my heart.

Luckily, I soon met up with Tarak Ben Ammar, the Tunisian producer whose groundbreaking vision Black Gold has been for years, and the film's maverick director Jean Jacques Annaud. Careful to phrase my question diplomatically but yet aware that I found myself in the presence of two filmmakers of extraordinary talent and thick skins, I posed my dilemma to them. Why would I see so much in Black Gold, and my Arab colleague dismiss it so easily?

Ben Ammar jumped in with his self-assured, successful businessman to the core timbre:

I'll answer as an Arab. There are 23 countries in the Arab world and they don't all share the same point of view. This is the work of a director, it's his POV, my POV and the one of the author. If there were cliches, certainly we were very careful not to have them there but cliches interpreted by different people are seen in different ways. You take any of the big epics, Lawrence of Arabia had cliches, Dr. Zhivago was killed when it came out. The Arabs are epidermic today about their image, and rightly so because they have been bombarded. Lets take film history, first it was blacks who were the bad guys, then the Native Americans for years, then the Arabs, every time there was a terrorist, he had a turban. So the Arabs are extremely sensitive about their point of view, on how they will be portrayed, but they'll also never agree.

The more contemplative, artistic side of this power equation, filmmaker Jean Jacques Annaud added his own wisdom:

Every movie I do about a topic, Quest For Fire was about very primitive men, widely the movie was very well received, but not by the specialists. When I did The Name of the Rose, I was destroyed by the Medieval specialist, when I did The Bear, my worst enemies were the bear specialists, those five people who have written books about bears. Black Gold is a piece of fiction and I hope that through maybe many details that will disturb them they will see it's a work that has been made with a lot of respect and love and talks about what I perceive and like in this part of the world and civilization.

Perhaps in order to fully enjoy Black Gold, one has to wholeheartedly believe in the magic of the movies, immerse oneself in a story written long ago, with larger than life characters and taking place in a fictional place that represents all Gulf countries and yet none. Or perhaps the film is caught in a battle as simple as the recent clashes within the Arab world, that same "us vs. them" mentality only this time directed against institutions like the DFI and Quinta that can finally call their own cinematic shots, no expenses spared, while most countries are still arguing over who their next leader should be.

The film is slated for a worldwide launch starting November 23rd, but alas, there is no scheduled release for the U.S. And to think that this would be the one country where we could most benefit from the subliminally positive message that Black Gold delivers. I certainly would want all who hold preconceived ideas about the Middle East to watch it and understand a little more about those we have called "them" for way too long.

Top photo of Annaud and crew setting up a sequence by © Brigitte Lacombe, all images courtesy of DFI and Quinta Communications, used with permission