IANNIS XENAKIS in his studio, Paris, early 1960s, archival exhibition print, 35 x 35 inches, collection of Francoise Xenakis, Photo by Adelmann

"I call architecture frozen music," Goethe declared. Almost two centuries later, Iannis Xenakis defrosted architecture, and a new kind of music was born. Not dependent on melodic lines, and only incidentally on rhythmic patterns and harmonic relationships, Xenakis' music is one of sonic contour, describing - or, rather, inscribing - sound clusters that exist at least as much in space as they do in time. Trained as an engineer, Xenakis was a practicing architect who then turned into a composer - without leaving the drafting table.

If his friend Edgard Varèse defined music as "organized sound," Xenakis determined an entirely new way to realize that organization. Until the Romanian-born Greek began moving arcs and blocks of clustered tones around as if designing buildings or bridges, composers had been moving sequences of notes around as if writing sentences. Music had never before abandoned its origins in the human voice so thoroughly; when Xenakis rooted it in habitable rather than syntactical structure, music took on a new kind of presence - a physical, or at least visual, rather than verbal, one.

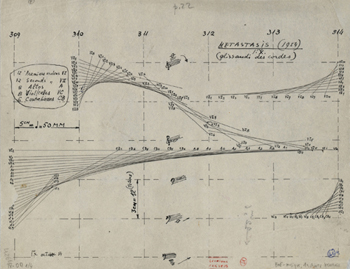

IANNIS XENAKIS, Study for Metastaseis, 1953, Pencil on paper, 9 1/2 x 12 1/2 inches, Iannis Xenakis Archives, Cliches Bibliotheque nationale de France, Paris

For the entirety of his career Xenakis built his music - or, if you would, composed his architecture. He applied mathematically derived "stochastic" principles of formal organization to his compositions that determined their structure, their movement through time, from spatial designs and linear graphs. To be sure, Xenakis cared about sound for its own sake. He was no mere number-spinner, computing dry mathematical relationships and translating them into bloodless musical scores, but was acutely sensitive to the way things reached the ears. Indeed, his architectural experience prompted a preoccupation with the acoustic properties of spaces, and his innovations extended to rearranging instrumental ensembles all over the stage and even the concert hall. But Xenakis wanted most of all to create a music of such palpable intensity that it makes you feel as if you're listening to things much bigger than you. Even if it's for a solo instrument, you don't just hear a Xenakis composition, you live in it.

In this day and age, retrospectives of composers make as much sense in museums as they do in concert halls. But a Xenakis survey makes at once more sense and more problems than most. His theories and even practices are dense and heady, more the stuff of science than of aesthetics - at best illuminating the aesthetics in science, but as often coming off as the science of aesthetics. The proof, as it should be, is in the sound, not the image. But in composing his note-thick pieces, Xenakis left behind a fascinating paper trail of mathematical, quasi-architectural, and even purely whimsical, doodle-like studies. Further, this retrospective, originating at New York's Drawing Center and ending its Los Angeles run Sunday at MOCA's Pacific Design Center space, brims with audio-visual moments that flesh out the composer's fascinating career and also his ambitious sense of presence and even theater.

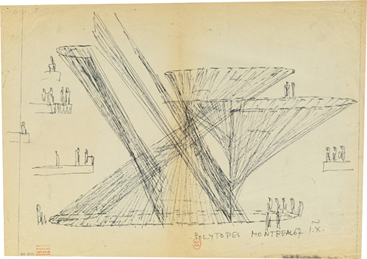

Xenakis' early life was lived in the shadow - and ultimately in the crosshairs - of a conflicted Europe, and especially a battleground Balkans. By his own account, his wartime experience found its way into many of his pieces, especially to the multi-media Gesamtkunstwerk series the Polytopes, staged in Greece, France, and even pre-revolutionary Iran. If MOCA's reduced re-staging of the latter Polytope, Persepolis, was any indication, these ferocious son-et-lumiere manifestations did - do - indeed commute the experience of war, at once terrifying and exhilarating, painful and transporting.

IANNIS XENAKIS, Study for Polytope de Montreal, 1967, Ink on paper, 9 1/2 x 12 1/2 inches, Iannis Xenakis Archives, Cliches Bibliotheque nationale de France, Paris

Philips Pavilion, 1958, postcard, 4 x 6 inches, Iannis Xenakis Archives, Cliches Bibliotheque nationale de France, Paris

The not-yet-composer found his way to postwar Paris, where he ultimately wound up working for Le Corbusier, no less, becoming a pioneering protégé of the prominent architect. Xenakis' succès d'estime was the Philips Pavilion at the 1958 Brussels World's Fair - or would have been, had Corbu been willing even to share credit with the young Greek in his office. In fact, Xenakis was mostly responsible for designing this revolutionary space, the first constructed entirely of parabolas. (From the documents, the pavilion, elegant yet dynamic, all spiky swoops and oblique angles, looks like the midcentury mother of Frank Gehry's bumptious buildings.) All he got to put his name to, however, was the brief piece of electronic music, Concret PH, that filled the Pavilion's entrance hall - and even that was overshadowed by the Poème Électronique composed by Varèse for the pavilion's central display. Xenakis broke with his employer over this slight; Le Corbusier later gave Xenakis his due, but by that time, his former apprentice had abandoned architecture altogether. That is, he had abandoned the profession of designing buildings, training his architectural impulses instead to the construction of music.

Xenakis returned fitfully to designing actual buildings throughout the rest of his life. The show documents a residence, for instance, he designed for fellow composer Roger Reynolds outside San Diego and a proposal for a concert hall at the outskirts of Paris (neither, alas, ever built). But after the Philips Pavilion, he committed himself to musical composition. The show is seeded with audio-visual moments, screens with earphones at which one can sit or stand and even a free iPod with a hefty playlist cued to various items on display. Even beyond the eye-and-ear moments the show consists as much of documental as of hand-rendered material, but it's all fascinating (not to mention handsomely and comfortably installed). Even the LP covers are cool.

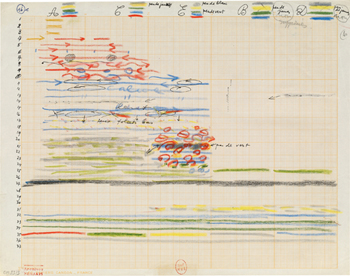

IANNIS XENAKIS, Study for Polytope de Montreal (light score), c. 1966, Color pencil on paper, 9 1/2 x 12 1/2 inches, Iannis Xenakis Archives, Cliches Bibliotheque nationale de France, Paris

Xenakis was opposed to presenting performers with graphically notated scores; but the diagrams and formal sketches he generated in determining the notes that ultimately landed on his music paper are as optically engaging and intellectually provocative as anything John Cage conjured. (No diminution of the American composer meant here; Cage's hand wielded its own calligraphic power.) Xenakis worked with a draughtsman's hand to unleash a five-decade parade of engaging, surprising shapes. In this regard, perhaps the high point of this survey is the video charting a "performance" of the 1978 Mycènes Alpha, the first of the composer's "UPIC" pieces. A computer program designed to read hand-rendered marks for sonic generation, UPIC sends a steadily moving vertical swipe across Xenakis' blobs and branches, the resulting sounds at once symphonic and galaxial in their roars, squawks and shivers. If he could not accept humans playing his graphics, Xenakis could apparently accept machines playing them. Once an architect...