OTTO DIX, Group Portrait: Guenther Franke, Paul Ferdinand Schmidt, and Karl Nierendorf, 1923, Oil on canvas, 15 3/4 x 29 1/8 inches, Nationalgalerie, Berlin

Olaf Peters calls the representational, highly topical style of painter Otto Dix "intransigent realism." In this, Peters marvels at the brute power and unstinting frankness the subject of his curation brought to his depiction of the world, and especially people, around him. Dix's portraits and social comments flirt with caricature, but, unlike George Grosz, his cohort in Dada subversion, Dix rarely distilled his jaundiced point of view into scalding cartoon (his 1924 print cycle Der Krieg - "War" - a notable exception). Rather, he chronicled his time and place by describing the psychological mindset(s) of human beings he knew and observed in a manner at once redolent with art-historical affect and preoccupied with the brittle, ravaged psyche he felt in the civilization around him. However dated Dix's art may now seem - not only by its Weimar-era harshness but by its equally aggressive conjuration of northern Renaissance and Baroque predecessors - its power and facility lend it a tortured authority that grips you at the beginning of his retrospective and doesn't let go. Buy the ticket and gird the loins.

At its outset, "Otto Dix," the painter's first major survey in the Western Hemisphere, curated by Peters, dumps us, appropriately enough, in the trenches, and viscera, of the First World War. Der Krieg, Dix's answer to (well, echo of) Goya, is the focus here, but drawings of everything from brains and intestines to camp-following prostitutes augment the grotesque immersion afforded by the cycle of fifty etchings. Dix served as a machine gunner through much of the fighting - it's a miracle he lived to paint the tale - and he regurgitated his experience with a viciousness born as much from detachment as from revulsion.

Nothing that follows is quite so ferocious, but there is an icy clinicality to Dix's purely visual regard even in Der Krieg that distances his work from the expressionism of the previous generation. To be sure, Dix owed a lot to his immediate predecessors, stylistically as well as spiritually; but, chastened by a true firestorm - made aware by direct experience not only of man's inner monstrosity, but of what happens when that monstrosity comes out - he needed to adopt a different stance. Not surprisingly, in the wake of such a disaster, other German artists adopted this same stance, and Die Neue Sachlichkeit - "The New Objectivity" - emerged from the rubble of a defeated empire.

OTTO DIX, Portrait of the Dancer Anita Berber, 1925, Oil and tempera on plywood, 37 5 /8 x 25 1/2 inches, Kunstmuseum Stuttgart

Actually, Dada emerged even as that rubble fell, and it was with that nihilistic bird-flip of a movement that Dix was initially associated, and remains associated to this day in most (non-German) minds. But the retrospective plays down this aspect of Dix's oeuvre, mostly omitting the paintings of crippled automatons and the snarky drawings and photomontages that connected him to the angry, politicized Berlin version of Dada. As opposed to Grosz, Heartfield, Höch, Hausmann, and the other Dadaists in Berlin, however, Dix was based in Dresden, at some remove from the street clashes and daily headlines of the capital and already involved in a search for a more profound, not to say enduring, means of commentary. He found it in the classicized expressionism of the "New Objectivity," an approach he helped create and promulgate, even beyond Germany's borders (and a phenomenon about which we in America are still too little apprised, even despite its influence on some of our favorite artists - look at Dix's own prefiguration of such popular latter-day artists as Lucien Freud and H. C. Westermann).

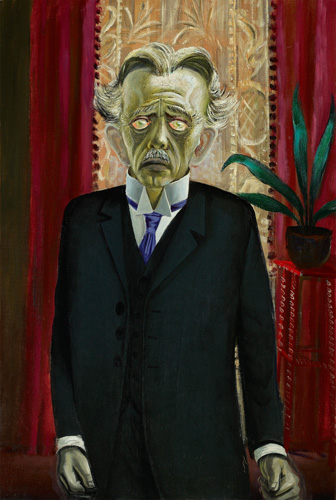

OTTO DIX, Dr. Heinrich Stadelmann, 1920, Oil on canvas, 35 3/4 x 24 inches, The Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

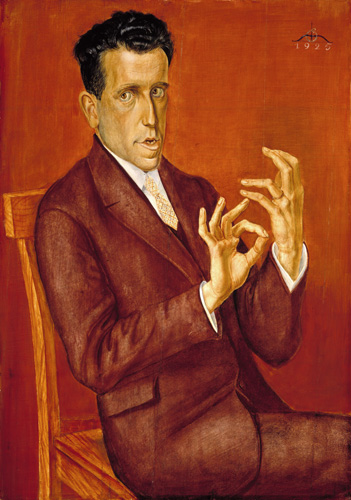

Die Neue Sachlichkeit served Dix well, both in portraying the decadence of man and society in caustic detail and in portraying the dignity of individuals with almost affectionate precision. Dix did not flatter his sitters, no matter how close he felt to them; if anything, he tended to exaggerate, however slightly, their more apparent characteristics - the heft of a surgeon, an intellectual's pallor, even the "Semitic" features of an art dealer (in eerie but unwitting anticipation of the Nazis' own distortions). These inflections read as tender celebrations of his subjects' distinctiveness - certainly in comparison to his rude typecastings of whores and their johns, or the horror- and pity-stricken renditions of profoundly wounded combat veterans. Every so often Dix did go after the bankers or the complacent bourgeoisie, but these exercises in mockery pale beside his more even-tempered - if no less harshly lit or drawn - images of a human species struggling to maintain its civility.

OTTO DIX, Portrait of the Lawyer Hugo Simons, 1925, Tempera and oil on wood, 39 1/2 x 27 5/8 inches, Otto Dix Stiftung, Vaduz

You can imagine what happened to Dix and his art as of 1933. But, just as he stayed in the trenches for so much of the Great War, he chose to go into "internal exile" rather than flee and leave his native land and culture to the barbarians who now appropriated it. As if to lay prior claim to German artistic heritage, Dix turned to painting Breughel-inspired landscapes, Düreresque portraits, and even Gruenewaldian religious scenes. To be sure, this was a canny way for a now-unemployable art professor to produce marketable artworks and put food on his family's table. But it was also a way of re-staking his heritage, of declaring that German art belongs first and foremost not to any sort of German state or even German Volk, but to German artists.

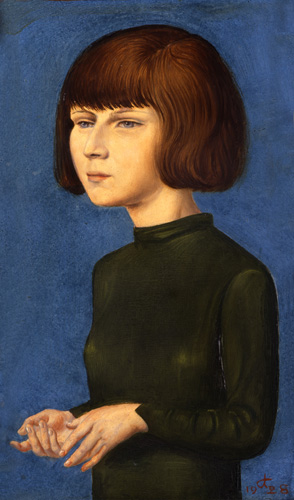

OTTO DIX, Portrait of a Young Girl (Erni), 1928, Mixed media on wood, 13 5/8 x 8 1/2 inches, Otto Dix Stiftung, Vaduz

Dix survived the Nazis, and he survived the sundering of his country - both West and East gave him props during the Cold War - and even the postwar "triumph" of abstraction. By time he passed away in 1969 a renewed interest in figurative painting - and in the reclamation of German modernism in general - had brought him a new round of honors. Dix apparently died with his boots on, and I wish the retrospective had at least sampled the output of his last three decades. He may have been the quintessential voice of the Weimar era, but he was also Otto Dix, one of the last century's most skilled and interesting painters, and what he cranked out in his kinder, gentler Autumn must still be of interest.

The retrospective ends its run on Monday, August 30, at New York's Neue Galerie. It then goes on to Montreal's Museum of Fine Arts (September 24-January 2).