The Ides of March have come and gone, but the ideas are sticking around pretty much through the month - ideas rumbling around that most un-ideal medium, painting. Conceptualists often decry painting's supposed idealessness, but, at its best and even short of that, painting brims with thinking as well as acting. It's a thinking peculiar to the medium, to be sure, which is why it gets dismissed - and, for that matter, prized - for its apparent vacuity. You don't have to be a painter to "get it," but you have to, er, be there. The thinking of painting is not a mystery (although it is part of painting's mystique), but you either have to need it (whether or not you paint) or be open to it. If you like painting, you "get" painting.

Everybody gets, and grooves on, Mark Grotjahn's new paintings, and not only because they're big and hang in yet bigger rooms (at Blum & Poe, 2727 S. La Cienega Blvd., thru April 3, www.blumandpoe.com). They even - perhaps especially - wow those of us who have been more puzzled than beguiled by the pale, luminous, but rather flat-footed geometries with which the Los Angeles-based Grotjahn came to prominence over the last decade. Instead of more such sly self-effacement, Grotjahn's current canvases (well, oils on linen-mounted cardboard) throb with gritty striations coursing every which way, but tending to coalesce into leaf-like or, more to the point, eye-like ovals at and just above mid-painting.

MARK GROTJAHN, Exhibition view, Blum & Poe Gallery

No question but that Grotjahn is conjuring faces, masks, weird visages that suggest the baleful glare of aboriginal deities. He is also conjuring a modernist tradition of celebrating - and, yeah, appropriating - such presence and power, as in the painting of Cuban surrealist Wifredo Lam, for instance, or the more oblique but similarly rough-hewn expressionist abstractions of such postwar painters as Jean-Paul Riopelle, Ernst Wilhelm Nay, and, you bet, Jackson Pollock. Grotjahn has evidently been refining this approach even while coasting on his neo-geoisms, and he makes this otherwise almost self-consciously dated manner work with a compositional vibrancy, similarly dynamic color (including a masterful balancing of dark and light), and a thorough command of scale: the burgeoning presences make sense only when they loom over us, harsh and anxiety-inspiring but not entirely antagonistic.

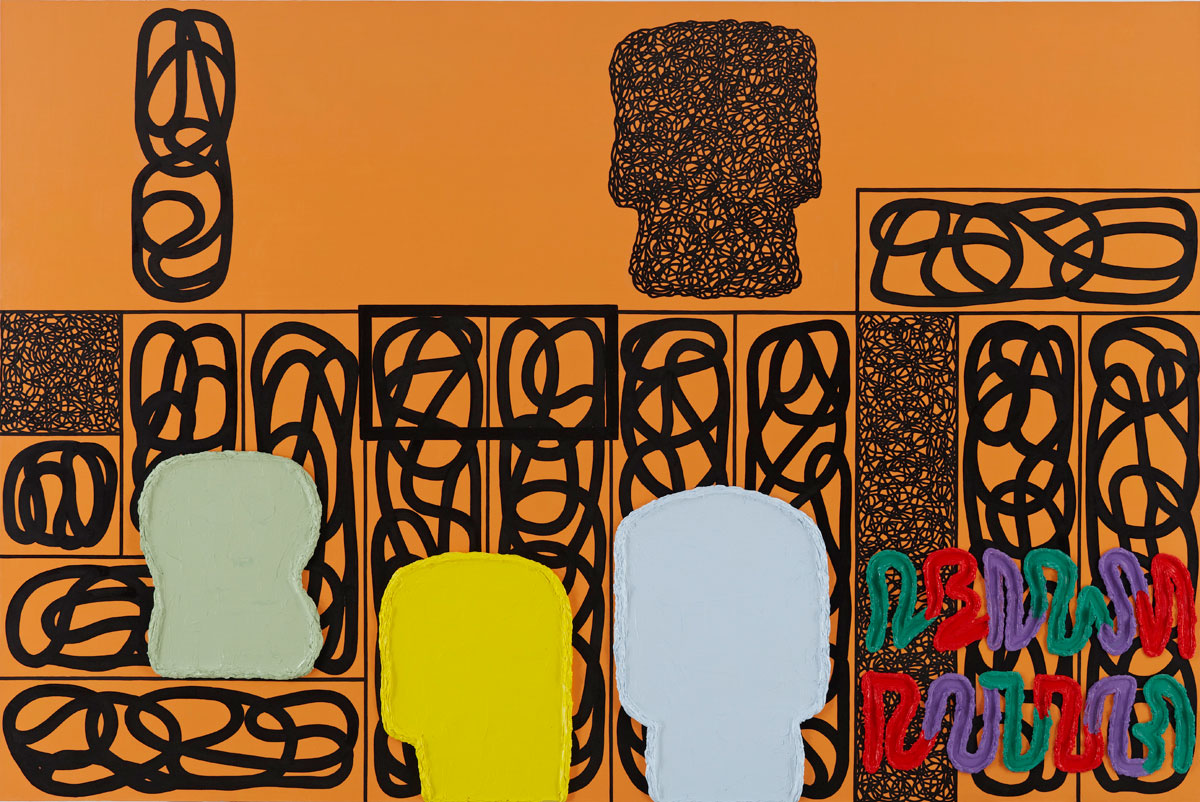

Next to Grotjahn's paintings, Jonathan Lasker's (at LA Louver, 45 N. Venice Blvd., Venice, also thru April 3, www.lalouver.com) might seem cramped and fussy in their self-containment. But that gnarled, pulled-away-from-the-edge quality is precisely what gives, and has always given, Lasker's compellingly odd abstraction its enduring energy. If line is a structural fundament of Grotjahn's work, it is the basic ingredient of Lasker's, the sinew as well as the bones of his imagery. There is an imagery in these welters of painterly scribble, after all. Lasker organizes his ropey doodling into compositions whose figure-ground relationships suggest cartoony cityscapes and still lifes - that is, when they're not winding themselves up in repeating contours and obsessive tangles.

JONATHAN LASKER, The Plan for Morality

Let's get Philip Guston out of the way immediately: despite all the lines, Lasker's oils look nothing like Guston's (not least in their brazen colors), but they do capitalize on a formal reasoning that stands equidistant from Guston's abstract and late-figurative styles. Perhaps this is because Lasker is influenced less by Guston than by the same visual language that influenced him, that of the comic strip. The flat, electric imagery of Lichtenstein's and Warhol's Pop art allows Lasker to ramp up the eye-affronting jangle; while Guston's humor was invested as much in caricature as in paint, Lasker's is purely formal, dependent on lines acting funny and on the luscious presence of pigment.

Given what painters are doing with paint, and with the near-absence of anything recognizable, imagine what they can do with more literal imagery - and with more than just paint. Nicholas DiLeo's paintings, showing (at LA Contemporary, 2634 S. La Cienega Blvd., thru, once again, April 3, www.lacontemporary.com) under the rubric "Super Syntax," are, if anything, even more ambitious than Grotjahn's or Lasker's. They are, after all, more willing to go all over the place, more willing to diffuse their meaning, more willing to let their visual strategy/ies unravel or gallop off untethered, more willing to fail. And fail they sometimes do, but not ignobly, and not even illogically. DiLeo, who works in LA (after years in New York), dumps a vast array of things - that is, images of things - into a single picture, risking it becoming a container for everything and a picture of nothing, a babble of voices rather than a chorus, a rebus assembled by someone who doesn't speak rebus.

NICHOLAS DI LEO, Exercise Guy

But DiLeo does speak rebus, he knows how to make even non sequiturs talk to one another, and when he can harmonize his mismatches, get speech balloons, Colonial portraits, abstracted diagrams, and folk-art animals to co-exist, they sing full throttle and joke with one another like long-lost army buddies. He does exercise a kind of super-syntax, organizing an improbable array of objects and references, topics and methods into symmetrical, strangely meaningful cosmologies. DiLeo's basic device for achieving such coherence is to cast it all in front of (and by inference "in") a landscape space, something that opens up backdrop into background and puts everything, no matter how incongruous, into a single atmosphere while maintaining the overall discontinuity. The mind remains assaulted, but the eyes make sense of it all.

For all the visual ruckus raised in various ways by the painters above, the still, small voice still has recourse to the discipline. Lee Bae's painting (at AndrewShire, 3850 Wilshire Blvd., thru March 27, www.andrewshiregallery.com), comes right out of Chinese calligraphy and a Zen-like mindset. Lee lives in Paris, but is clearly affected by the model of fellow Korean Lee U-fan, guru to a whole school of Japanese abstractionists, in his exploration of a painterly minimalism.In actuality Lee's art is less painterly than it seems; he renders the deep, dark shapes and strokes that seem frozen into icy panels in charcoal, not paint, and he employs acrylic medium only to "freeze" his black bars, spirals, and other gestures onto (or is it into?) the pictures. This robs them of the texture other artists (Richard Serra, for example) wont to inscribe black shapes on white give them; they seem instead as lacquered as jewel boxes, but at the same time as buoyant as clouds.