Is the medium still the message? Is it still possible to admire and evaluate the mediation of experience, or are we so far inside that mediation that our lives are no longer distinct from it? Is the unexamined medium not worth living? Then perhaps one of art's principal purposes is now to provide such examination. Two shows in northern New Mexico - off the beaten media path, perhaps, but actually not as far off as you might think - provoke such thoughts because they examine media and consciousness, implicitly and otherwise.

Download file

"The Dissolve" at SITE Santa Fe, photos by Brandon Padron

SITE Santa Fe's latest International Biennial, "The Dissolve," consists entirely of projected art, that is, art that exists primarily, or entirely, on-screen. There isn't one laptop in the show, however; every film, video, DVD, or what-show-you is seen in a dedicated viewing context, whether cast upon a large screen, seen on a small screen in a booth, or even peeked at through an updated version of a side-show mutoscope. Including as it does filmic work going back to the 1920s (and in one instance 1900), this biennial does not focus on contemporary art exclusively, but posits a trajectory of contemporary artistic activity as a tradition.

By concentrating on the conditions of animation, above and beyond any issue of film/video, analog/digital, or any other technical distinction, "The Dissolve" examines one of the practices most central to the modern aesthetic(s) of disjuncture and fabrication. Most everything in SITE's Eighth International Biennial is, or at least appears, in motion, and everything in motion is an illusion. Whether we're computer natives, TV natives, or movie natives, every one of us is a product of this illusory awareness; what distinguishes us, finally, is not whether we've gotten our cartoon buzz from pre-feature screening, Sunday morning programming, or on-line gaming, but how invested our lives are in such fantasy - and, conversely, how much we regard it as "art."

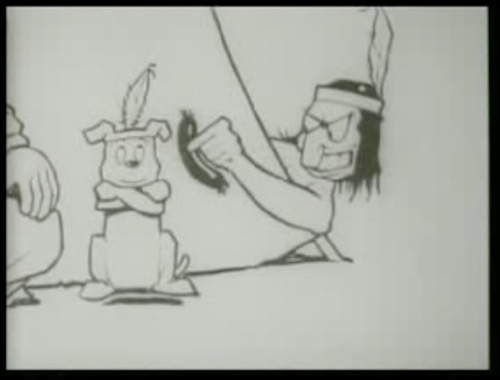

FLEISCHER STUDIOS, still from "Big Chief" Ko-Ko, 1924, 35mm film transferred to DVD, 7 minutes, Courtesy Inkwell Images, Morley MI

The earliest work in "The Dissolve" is commercial, or proto-commercial, designed by the Fleischer Studios or even Thomas Edison for silent movie theaters. The closest such historical work comes to the artistic avant garde is in Dziga Vertov's rare animation Soviet Toys - a predictably anti-bourgeois screed done with a very fine line - and Lotte Reiniger's Adventures of Prince Achmed, probably the first feature-length animated film, made with shadow puppets (intriguingly anticipating Kara Walker's work, which is also represented here). Early abstract animators are nowhere to be seen. In fact, "The Dissolve" avoids abstraction: it concerns itself with technical innovation put at the service of narrative. Once you accept that curatorial strategy, everything falls into place.

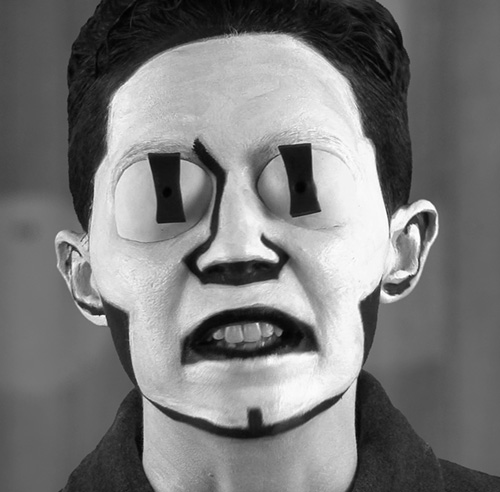

WILLIAM KENTRIDGE, still from History of the Main Complaint, 1996, 35 mm film transferred to DVD, sound, 5 minutes 50 seconds (5 of ed. 10), Collection Ilene and Michael Salcman

AVISH KHEBREHZADEH, Theater III, 2010, Oil on gesso and wood, 90 x 135 inches, with still from Edgar, 2010, Video, sound, approx. 3 minutes, Courtesy of the artist

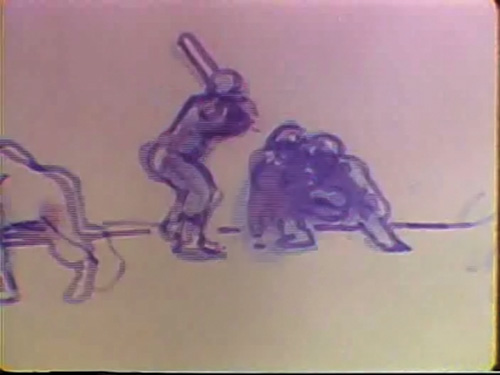

Except that some of the narratives are more linear than others. All the moving pictures in "The Dissolve" are about something, most also showing something "recognizable"; but not very many hew to classic narrative teleology. In this respect, "The Dissolve" argues, animated art is closer to music than it is to theater. Plenty happens, whether in William Kentridge's elaborately drawn tale of a man hallucinating in a hospital, Maria Lassnig's self-mocking autobiographical song, Avish Khebrehzadeh's parable-like comics projected into a fixed proscenium, Robert Breer's cascade of collage elements and rotoscoped images, the stereoscopic choreography of Bill T. Jones and his Openended Group, or George Griffin's hand-cranked motion study. But it doesn't necessarily "add up." Even when it does, as in Joshua Mosley's tender, muted tale of a statue polisher, Mary Reid Kelley's epic, elaborate World War I dramatization, or Christine Rebet's awkwardly rendered two-screen account of Rococo-era gamblers and puppeteers, the story arch we expect from films - including cartoons - gets lost, usually deliberately, in the translation.

ROBERT BREER, still from Bang!, 1986, 16mm film transferred to DVD, sound, 10 minutes 17 seconds, Courtesy of the artist and gb agency, Paris

MARY REID KELLEY, still from You Make Me Iliad, 2010, HD video, sound, 7 minutes 22 seconds, Courtesy of the artist

What holds the experience of "The Dissolve" together is not the variety of stories being told, but the mixture of techniques, contents, and effects - and sizes and sounds and textures - one experiences - collects, really - as one moves from room to room. The sound leakage is minimized, its low babble filling the otherwise quiet spaces until you position yourself directly below each "talkie" picture's acoustic projector (or in a few more intimate cases don the headphones). Ironically, the cinematic experience of sitting in a darkened room here gives way, even when you can sit down, to the sense of flow you expect and want from a show of static pictures. On a certain level, at least, it's Pictures at an Exhibition come to life, the "pictures" not simply showing what they show, but moving with it.

Modest Mussorgsky composed Pictures at an Exhibition around the time Walter Pater opined that "all the arts aspire to the condition of music," that is, music's condition as an abstract, disembodied art allowed it to move its audience more deeply and profoundly than could any other art form. Other time-based arts (theater, dance, poetry) had to incorporate music even to get close. And the poor visual arts! Only the deaf could enjoy them completely. In the wake of Pater's dictum and the gradual dissolution of established artistic practices toward the end of the 19th century - toward the "total work of art" Wagner sought in his operas - visual artists strove more and more to inhere the "condition of music" to their work. Abstract cinema was one means, but hey, what about us painters?

Mussorgsky's fellow Russians led the way in studying - scientifically and otherwise - the relationship(s) between optical and sonic reception. Must be something in the vodka, but such synesthesia, the urge to paint sound and compose with color - as well as to taste shapes, smell light, etc. - seems a particularly Russian thing, or did at least in the pre-Soviet era. Scriabin's color-symphonies, Kandinsky's "improvisations," and all manner of elaborate invention - not to mention neo-spiritual movements such as Madame Blavatsky's Theosophy - spurred experiment in cross-media artwork throughout the western world about a hundred years ago.

EMIL BISTTRAM, Musical Notes, c. 1951, Oil on canvas, 50 x 80 inches, Courtesy Peyton-Wright Gallery, Santa Fe

The Albuquerque Museum's "Sensory Crossovers: Synesthesia in American Art" takes a look at how that Russian attitude washed up on our shores. Next to Picasso, Kandinsky was probably the biggest influence on our avant garde in the 1910s and 20s, his treatise Toward the Spiritual in Art giving permission to painters and sculptors to depict what they sense, not just what they see - a concept even more liberating for American artists than for Europeans, given the skeptical materialism and restrictive fundamentalism that ever rules our society. "Sensory Crossovers" takes up where other recent studies in synesthetic art have left off, collating artwork that translates not just musical pitches and chords but natural sounds into visual form(s).

WILLIAM MEYEROWITZ, The Overture, c. 1930, Color etching, 8 x 10 inches, Collection H. Girard Jackson

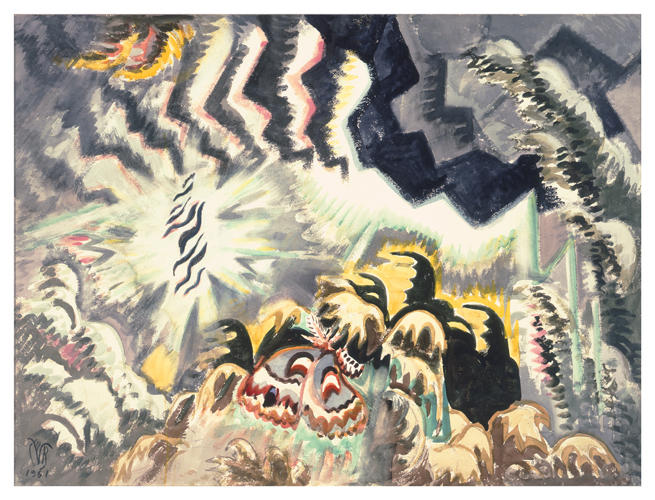

CHARLES BURCHFIELD, The Moth and the Thunderclap, 1961, Watercolor and charcoal on paper, 36 x 48 inches, Courtesy Charles E. Burchfield Foundation

"Sensory Crossovers" provides a herky-jerky ride, zooming in on the sonically impelled work of one artist and leaving the equally acoustic art of another represented by one painting - or none at all. (If Stanton MacDonald Wright weighs in, for instance, where is the even more music-besotted Synchromist Morgan Russell?) This is by no means an exhaustive survey of American synesthetic painting, not even from the prewar years. (The contemporary embodiment of synesthesia here is negligible.) And it is uneven in its focus, hanging expressionistic depictions of musicians by Theresa Bernstein next to "pure abstraction" derived from or based on musical structures by William Meyerowitz, Charles Burchfield's landscapes melting into sound near to the calligraphic notations of Clyde Connell, and so forth. The rubrics are thankfully clear and emphatic, separating sound sourced in music, for instance, from sound sourced in nature. And there are enough terrific paintings in the show to make for a gratifying visit. There are also enough surprises for specialists and synesthusiasts (like myself) to keep us on our toes. Who knew, for instance, that the New Mexico Transcendentalists produced its own abstract animator, Horace Towner Pierce?

ARTHUR DOVE, Fire in the Sauerkraut Factory, 1936-41, Oil on linen, 10 x 12 inches, University of Mississippi and Historic Houses, (c)The Estate of Arthur G. Dove

Pierce is represented by a rash of small, elegant, airbrushed drawing-collages. He's the only historic abstract filmmaker here; as opposed to "The Dissolve," others of Pierce's ilk such as Oskar Fischinger and Len Lye (to name only American-based filmmakers) are conspicuous here by their absence. The Transcendentalists were a New Mexico-based group, the significance of their thought and accomplishment still under-regarded by art-historical orthodoxy. "Sensory Crossovers" makes the opposite mistake, taking a New Mexicentric viewpoint that privileges Georgia O'Keeffe and her Stieglitzian friends (Arthur Dove, Helen Torr, Charles Demuth, Burchfield), for instance, or the Taos couple Louis Ribak and Beatrice Mandelman over equally apposite practitioners such as Fischinger and Russell. Nobody included in the historic part of the show (with the possible exception of Bernstein, who was clearly painting musicians, not music) should have been excluded, and the inclusion of out-of-the-blue figures such as Augustus Vincent Tack, Agnes Pelton, and e. e. cummings (yes, that e. e. cummings) argues with very good examples for an exciting revision of American art history. "Sensory Crossovers" may be less than the sum of its parts, but all the juicy items on view - and the show's basic premise - still make the show a must-see.

AGNES PELTON, Fire Sounds, 1930, Oil on canvas, 34 x 24 inches

Both shows are on view until January 2. Remaining events at SITE include the lectures "Out of Shadows, Silhouettes in Art" (November 9) and "Video Into Art" (November 16). At the Albuquerque Museum, local artists Kristen Loree and Jack Ox perform and visualize Kurt Schwitters' classic sound-poetry score Ursonate (October 24), Jonathan Chenette's composition Onomatopoeia (based on a contemporary work in "Sensory Crossovers") is premiered (November 14), and there are lectures on "Strange Horizon: Where the Senses Meet the Screen" (November 21) and "Creativity, Synesthesia, and the Brain: Mixing Metaphors" (December 19). At the University of New Mexico Art Museum (until December 18), "To Form From Air" looks at "Music and the Art of Raymond Jonson," a central figure in the Transcendentalist group.