For nearly two years, public opinion has grappled with the prospect of intervention amidst the failed states of Syria and Iraq, and has most often favored intervention. But should we read much into polls showing American support for sending ground troops into Syria or Iraq? According to recent surveys, a majority of Americans (53 percent) favor sending ground troops into Syria or Iraq. They are even more supportive of airstrikes: More than 7 in 10 support the use of strategic airstrikes.

Now, Americans are good at war. The American public favors war, especially in response to perceived, imminent external threats. When posed with the possibility of war, in theory, Americans like the idea of invading other countries. In practice -- when lives are actually lost -- they like invading other countries much less. When an invasion seems like it might be costly, Americans often prefer more limited airstrikes or no military involvement at all.

A naïve reading of the polls might suggest a military option -- either ground troops or airstrikes -- would play well politically. One of the historic fears of politicians is that they will get caught on the wrong side of a popular war. But, war sentiment in the public is a bit more nuanced. Indeed there is good reason for skepticism.

First, where Americans are generally uninformed about domestic politics, they know even less about international affairs. In 2012, for example, just 50% of Americans could identify Syria as one of four choices when it was highlighted on a map (here). A more recent survey (here) found roughly a third of Americans do not know what country ISIS is based in, perhaps indicating that Ambrose Pierce was right when he observed that "war was created to teach Americans geography." Many of the opinions expressed in surveys then reflect not well formed or stable political attitudes, but responses dependent on context and question wording.

Second, as research by political scientist Adam Berinsky points out, public opinion on international conflict generally mirrors elite disagreement. When partisan elites are in agreement, the public generally follows along. When partisan elites disagree, public opinion reflects the level of elite conflict. Public opinion on the use of military force in Syria neatly mirrors partisan elite divisions. Republicans are most supportive of the use of ground troops (71 percent), Democrats are least supportive (39 percent), and Independents fall in between (53 percent). Overall, public disapproval of the use of force typically follows (rather than informs) elite opposition.

Third, public preferences for using military are contingent upon context though many Americans adopt a standing preference (or posture) in favor of the use of military force. Early research into the structure of foreign policy belief systems found that militarism -- a preferences for "get tough" responses in foreign affairs -- played the single most important role in structuring U.S. foreign policy attitudes. And there is also a militant religious dimension at work. Nationalistic political beliefs and traditionalistic Christian beliefs -- messianic militarism -- is another credible explanation for the origins of militaristic postures toward foreign affairs.

Curiously, a militaristic posture on foreign affairs signals strong confidence in the military but not always an individual's willingness to serve in the military or fight in individual wars. A recently released Harvard Institute of Politics survey, for example, reports that 60 percent of Millennials supported ground troops in Syria or Iraq but only 14 percent would definitely join or consider joining if the U.S. needed additional troops to win that fight. Millennials are not alone. When asked if they would be willing to fight for their country if there was another war in the World Values Survey in 2011, 42 percent of Americans said no.

So, where are Americans willing to make war recently? We looked at some recent questions on support for military action, across a range of political contexts.

•In May 2009, 59% of Americans supported using ground troops if the Taliban overthrew the government in Pakistan.

•In October 2007, 61% of Americans favored ground troops in the Darfur region of Sudan "along with troops from other countries, in an international peacekeeping force."

•In August 2003, 61% favored the presence of U.S. ground troops as part of an international peacekeeping force to help end the civil war in Liberia.

•In June 1999, 66 percent of Americans supported the presence of U.S. ground troops for international peacekeeping in the "Yugoslavian regions of Kosovo, Serbia, and other areas regions of the Balkans."

•And, this past August, 65% of Americans agreed with using military force against Iran if the Islamic Republic broke a nuclear arms agreement.

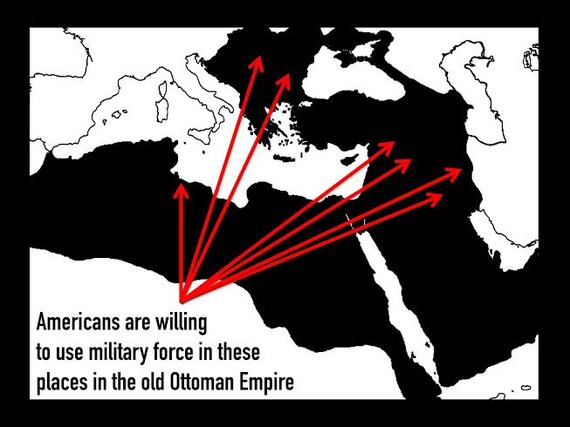

Support for the use of military force, however, is not automatic for every hotspot. In March 2014, only 12% support using ground troops and only 17% supported limited airstrikes to intervene in the Ukraine in light of Russian encroachment. In 2006, only 14% supported using ground troops against North Korea if they did not stop developing nuclear weapons. The public may be accounting (imperfectly) for perceptions of risks in support for military inventions or may be reflecting divisions among our elite political leaders. Either way, militarism as a defining characteristic of American foreign policy beliefs does not guarantee support for every military use of force. But it appears that Americans really do like invading the former Ottoman Empire.

Several patterns emerge when looking at support across context. Support for ground troops is typically greater when U.S. troops would be part of an international force and when a longer time frame or the number of troops is not specified. So, when we fight, we like to take along some backup. When force can be used quickly, with minimal American casualties, and elite partisan agreement, the public is almost always willing to go along -- the legacy of Gulf War I, which was the original Game Boy war, fought out quickly, on video, and with minimum cost to the Allied Coalition. The U.S. Invasion of Grenada in 1983 which ended quickly, without longstanding commitments, and with widespread declarations of victory might be the best prototype for public supported military action.

More involved uses of force, like the invasion of Iraq to overthrow Saddam Hussein in Gulf War II, better illustrate the fickleness of public opinion. From 9/11 terrorist attacks until the beginning of the Iraq War, 60 percent of Americans supported the use of ground troops to remove Saddam Hussein from power. It is perhaps worth noting that at the same time 64% of Americans would have supported using ground troops to invade Afghanistan. In light of the terrorist attacks and limited partisan opposition, the target for military action was less important than the cause.

Support for the Iraq War remained relatively strong until the mission took more time, money, and American lives to accomplish and as elite opposition grew. The percent of Americans saying the war was the right decision subsequently declined from 72% at the beginning of hostilities in 2003 to 47% after two years later in 2005 to just 38% in 2008. Exit poll data from the 2004 election indicate that it was the conflation of the Iraq War as a pat of the War on Terror that that maintained public support. This was the case even though the Iraq invasion was explicitly termed to be not part of the War on Terror in 2002 and 2003.

Given the complexities of defeating ISIS militarily in Syria, one would expect that initial public support for the use of ground troops would wane over time. Militaristic postures toward foreign policy, rooted in nationalistic and Christian fundamentalism, may provide initial but not lasting political support. Overall, when politics moves beyond the water's edge and into questions of military invasion, it is best to think where public opinion is likely moving and not where it currently resides.