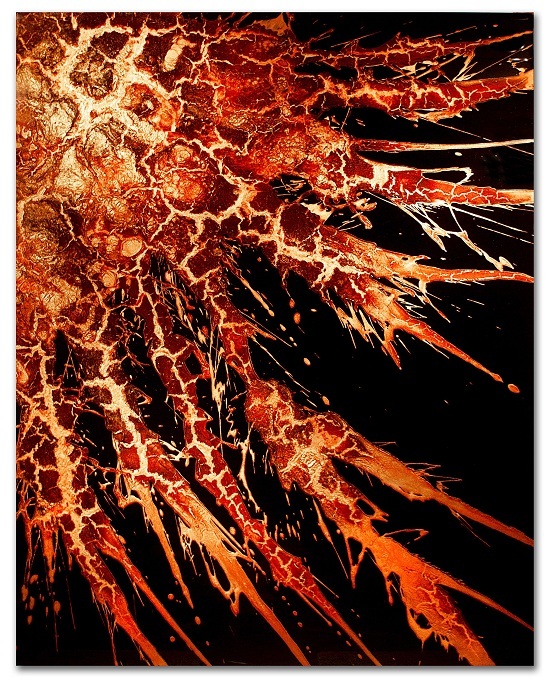

FKTS 19 is a new work by Jordan Eagles at The Butcher's Daughter in Ferndale. Instead of paint and pigment, the artist preserves animal blood and copper under shiny layers of resin. (Courtesy of the artist and The Butcher's Daughter.)

Blood is such a loaded symbol that sometimes art critics can't see past it. The sensational response to his chosen medium -- animal blood -- hasn't encumbered Jordan Eagles' soaring success in the New York art world. Now Metro Detroit art goers can view his works in person at The Butcher's Daughter. Many critics try to understand Eagles' work through idioms of art's past: from the drips of abstract Expressionism of the 1950s to the ritualistic sacrifices performed by Viennese artists in the 1960s. But these simplistic comparisons neglect the new symbolic meanings blood has acquired in millennial popular culture.

Gore and splatter films emerged in the late 1950s and 1960s; they were pop culture contemporaries to Performance and Body art. Our fascination with these films' carnage parallels a rise in extreme photojournalism showing real-time images of the wars in Korea and especially Vietnam. For the first time in American history, we were divided over America's involvement in war. The explosion of bloody images on TV and in film seems to accompany the increasing complexity and diversity of our moral responses to them.

Today, TV shows like Dexter and True Blood prove that we no longer unilaterally pronounce killing as good or evil. In fact, our cultural relativism actually permits us to empathize with -- even idolize -- serial killers. This cultural shift recasts the roles of blood and violence in our ethical debates. As audience members, we're forced to acknowledge that Dexter, a fictional murderer of criminals who escape the legal system, is neither good nor bad. Our rush to judgment is tempered by the ethical complexity of vigilante justice, and we begin to understand Dexter's fascination with blood. When we overcome -- or lose -- the cultural tendency to recoil from violence, we see blood's beauty and we marvel at splatter patterns, which recall astronomical formations.

Eagles' paintings hit similar chords in our aesthetic tastes because one can't help but acknowledge their aesthetic beauty. The works are as gorgeously crafted as the finest Japanese lacquer ware, but the real power is the strange sense of time-suspension that overtakes us as we stare and contemplate the images.

What happens in that moment when we become lost in Eagles' blood patterns? It isn't just fetishism. We're not hypnotized at the sight, but are actually performing a rigorous if unconscious ethical debate: how can a substance that denotes death have such spectacular beauty? Literary critic Frederic Jameson might describe this debate as "utopianism after the end of utopia." By that, he means that in our contemporary, postmodern culture, we have carved out new space to hold previously unfathomable visions for the future (and, retrospectively, of the past). When our traditional associations with blood involve either purification and redemption, or injury leading to death, perhaps Eagles is offering a third way to view the material: as a challenge to our black and white ethical codes. Blood and butchery, and our complex relationships to them, indicate that postmodern society lives in an ethical and aesthetic grey. Eagles neither affirms nor denies this ethical abyss: his work merely invites us to ponder over it.

John J. Corso teaches art history at Oakland University in Rochester, Michigan. He strives to write criticism that is 'partisan, passionate, and political.'