One of the most telling moments in the new documentary film Blood on the Mountain draws from 2008 footage of former Massey Energy CEO Don Blankenship calmly mumbling his replies to numerous questions on mine safety at a hearing. When asked if he knew how many coal miners had died in Massey mines in the eight years since Massey became a publicly traded company, the notorious "dark lord" of the coal industry shook his head and said no. Filmmakers Mari-Lynn Evans and Jordan Freeman allow for a gut-wrenching moment of silence, having methodically chronicled the industry's treadmill of violation-ridden disasters, and then provide the answer: 52 deaths under Blankenship as CEO of Massey Energy.

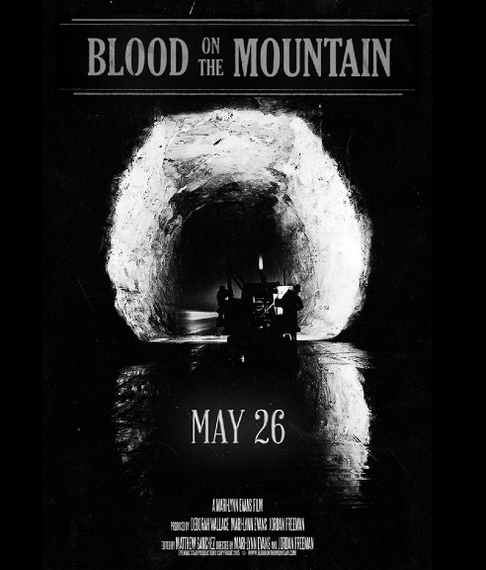

Unfolding with the plaintive air of an elegy, Blood on the Mountain captures this blatant disregard for the health and lives of coal miners -- and the mountains they call home -- as a timely reminder of the legacy of an essentially outlaw industry and its 150-year reign in West Virginia.

Yes, Virginia, there is a coal war in Appalachia, as defiant West Virginia-raised attorney Bruce Stanley tells the filmmakers, admonishing them to get the narrative right: "a war waged by coal on West Virginia."

The world premiere of this compelling film documentary at today's Workers Unite Film Festival in New York City couldn't be more timely, on the heels of West Virginia coal-chemical spills, a mounting health crisis from strip-mining and black lung disease, and dangerous coal-slurry impoundments readying for the next foretold Buffalo Creek-type disaster.

And as viewers watch the film this week, Big Coal-bankrolled members of Congress will continue to deny the deadly costs and health impacts of strip-mining, coal companies will abandon miners and mines in bankruptcy, and the rogue elements of the industry will take one last mountaintop-removal blast at the region before picking up and moving to the Illinois Basin or abroad.

As the film's best informants, local residents and former union coal miners like Terry Steele pull no punches. "They [couldn't] care less about this place," Steele says, noting that 80 to 90 percent of the mineral rights in his coal-rich county are owned by absentee corporations, adding that they "have no connection to land or people.... [W]hen they get everything they can get from it, they're like locusts."

While the coal industry did not begin in West Virginia -- and continues in 20-odd states -- Blood on the Mountain shows how the industry's stranglehold has always defined the state's corrupt politics and diminished economy, where regional lackeys do the bidding for absentee corporations, even at the expense of their own health, environment and livelihoods.

It's such an old and tragic history -- and it continues to flourish today, in the guise of political buffoons like U.S. Sen. Joe Manchin, a coal peddler who goes from one media-packed disaster after another.

Filmmakers Evans and Freeman have collaborated on several other films based in the region, including Coal Country and the PBS series The Appalachians.

"We had no no idea what blood lay under the graves," Rev. Ron English says, discussing the film's historical sweep, which dates back to slavery. Such historical oversight, English notes, makes the state, and the nation, "dishonest with ourselves, but we bring dishonor on our heritage."

That heritage for West Virginia has always ranged between repression and resistance -- courageous coal miners fighting bloody battles for union representation and fair wages and work conditions, fighting battles between themselves and, ultimately, waging a war on the mountains themselves as strip miners. It's a legacy of a century-long war of attrition by revolving coal companies to break down and divide the miners, their communities, and their land.

A former Massey miner's recorded voice laments Blankenship's union-busting ways, which eventually shattered and reduced the once-heroic United Mine Workers to a tiny corner of influence: "We had to produce to keep our jobs." Told that 1,000 people were waiting for their jobs, he adds, "I felt like that lump of coal was more important than a human being's life."

Thanks to its historical perspective, Blood on the Mountains keeps hope alive in the coalfields -- and in the more defining mountains, the mountain state vs. the "extraction state" -- and reminds viewers of the inspiring continuum of the extraordinary Blair Mountain miners' uprising in 1921, the victory of Miners for Democracy leader Arnold Miller as the UMWA president in the 1970s, and today's fearless campaigns against mountaintop-removal mining.

And the kicker: Don Blankenship now stands on trial for charges of conspiracy to violate mandatory federal mine-safety and health standards.

"The land erased by man," a documentary clip from the 1970s warns, showing how the abuse of the land has always gone hand in hand with the abuse of the miners, "then the machines erased man."

Nearly a half-century later, Blood on the Mountain asks a similar question: What will it take for the nation to end the war on West Virginia, to be honest with ourselves about the toll of our coal-fire electricity on the lives of miners and mountaineers and not simply abandon the region to the whims of a volatile market but recognize our historical debt to coal mining communities?