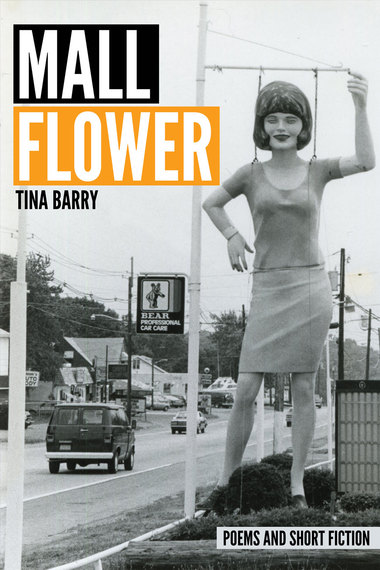

Tina Barry's poems and short fiction have appeared in numerous literary magazines and anthologies, including Drunken Boat; Elimae; Lost in Thought; Blue Fifth Notebook; Exposure, an Anthology of Micro-fiction (Cinnamon Press, 2010); and Veils, Halos and Shackles: International Poetry on the Oppression and Empowerment of Women (4/2016). Mall Flower, her first book of poems and short fiction was released in 2015 (Big Table Publishing). Barry is a Pushcart Prize, Best Short Fiction and Best of the Net nominee. She lives in upstate New York.

Loren Kleinman (LK): Can you talk about why you chose to mix the collection with prose and traditional stanzas? Do you think the combination of long and short lines creates a stronger emotional impact?

Tina Barry (TB): Mall Flower is a collection of poems, short and flash fiction and hybrids of the two. I was less concerned with form than whether or not the pieces supported the themes I explored: alienation, loss of a parent, sexual awakening and its decline.

Several of the poems in the first sections focus on my parents' divorce when I was a child. I thought the short story, "Greetings from the Clarks," about a friendship between two women who bond, and sometimes compete, over who has the lousiest father, needed to be in the book too. The women in the story are in their thirties, and yet their fractured relationships with their fathers continue to color their lives. I included pieces with a mix of light and dark. There's a lot of humor that helps balance some of the darker work.

Long and short lines? Yes, always. Few of us have lives that meander along without a crisis or detour. A stanza or paragraph with a few stops and starts mirrors that experience.

LK: I love the integration of past and present with visions of the future. How does being a Mall Flower let us make keen insights and observations about our lives? About other's lives?

TB: Thank you, Loren. I guess being a Mall Flower applies to anyone who's had a life-changing experience at an early age. Mine came at seven, when my parents divorced. Keep in mind that this was in the mid-Sixties when divorce wasn't as common as it is now. And theirs was as acrimonious as they get. I can remember thinking that I had never really looked at my parents as anything but my parents; I hadn't really noticed them as individuals with their own needs and frailties. That experience made me very watchful, very interested in adults and what made them tick. It made me older than my peers, more introspective, careful. I could, or thought I could see beneath the surface, and I guess that searching for subtext is what you've observed in my work.

LK: What types of poets and poetry influence your writing? What is your reading process like?

TB: I love a good story and I'm drawn to poets who tell them. I'm a fan of Sharon Olds, Dorianne Laux, Joseph Millar, Diane Wakoski, Kim Addonizio, and Jean Valentine's brief, elegant poems. I've been reading Matthew Dickman's work and admire how he can spin a story into improbable places and then reel it back in.

I read for story and imagery first, then music, and then form. I look for where the poet chooses to break lines. How those choices change meaning and sound. How they work with space.

LK: Can poetry ever be mastered? Why?

TB: Yes, I think it can. Many years ago, I heard May Sarton read a poem about her father. She read with such emotion, such longing, and yet it was a tough poem, not at all sentimental. The words were her truth. I remember thinking, That's perfection. For me, though, I doubt I'll master poetry, and I'm okay with that. Glad actually. I'm not sure what I'd do without the beautiful torture of writing a poem.

LK: My favorite poem is Peonies. I read it over and over again. Can you talk about that line: I am here for the peonies?

TB: Thanks, Loren. I'm glad "Peonies" resonated with you. I think of "Peonies" as flash fiction, but it could be a poem. Who knows what a poem is anymore? The boundaries of what makes a poem or a piece of prose are so fluid.

So, that line. The character in the story is confused about her attraction to her neighbor. With his "droopy stomach over droopy shorts," he isn't exactly GQ material. But they have this routine where they wave like long-lost friends every time she drives past his house, and she loves that. He's touched something in her. She tells herself she's intrigued by his gorgeous flower garden. So it's all about his garden, as she changes into a pretty blouse and dabs on perfume. And it's about the garden as she goes to his house, where she finds him in a shed. "I am here for the peonies," she says. He gets the subtext a second or two before she does.

LK: If you could build a house out of poems, which ones would you choose?

TB: I love that question. I can't narrow my poems down to a few; I'd have to say all of them. They're all a jumble of my past, present, and future, so to build this metaphoric house without one of them, would be like forgetting a floorboard or designing a room without a window. I guess every poem is really one nail in a little house, and every house a poem.