Top of the Barnes (behind Philadelphia's Free Library): Green roof on right. Gallery mock-ups on left, with clerestory windows that bring diffused natural light into the galleries below. In the middle, a cantilevered light box admits filtered and diffused sunlight into the event space beneath it. Entrance is on the far right, at the opposite side of the building from the gallery wing.

In their misbegotten effort to save the financially challenged Barnes Foundation by moving and greatly expanding it, its leaders have seriously undermined their institution's core values. A celebrated repository for some of the world's most ravishing Impressionist, post-Impressionist and modern masterpieces, the Barnes last week completed its transition from a bastion of authenticity to a compromised fake.

The bizarre project (memorialized in a 2004 court decision) to replicate in Philadelphia the galleries of the original 1925 facility in Merion, Pa., flagrantly disregards a primary mission of art institutions -- to defend the glory of the original against the taint of the spurious. The Barnes once upheld that principle to the point of fanaticism, not even allowing copies of its artworks to be made. Now the institution itself is counterfeit.

In taking the controversial assignment that put them at odds with some of their professional colleagues, as well as with many in the art world who cherished the jewel box in Merion, architects Tod Williams and Billie Tsien got the chance to design impressive, well-crafted facilities for two eateries, a leather-seated auditorium, an inviting gift shop, sleek classrooms, a tree-planted atrium, a special-exhibitions hall, a conservation studio and an expansive sky-lit event space with somewhat awkward, corridor-like proportions:

Light Court, with herringbone-patterned floor of ipe wood, recycled from the Coney Island boardwalk, Brooklyn, NY. Doors leading to the galleries are at the left, just past the speaker's podium.

But the architects' central task was one that would make many, if not most, contemporary architects cringe -- dutifully recreating (with some streamlined details, ceiling alterations and improved lighting) the Barnes' 12,000-square foot original galleries, now dwarfed by 81,000 square feet of additional space.

Left to right: Landscape architect Laurie Olin, architects Tod Williams and Billie Tsien. Seated: Barnes president and executive director Derek Gillman, trustee and building committee chair Aileen Roberts

Within the recreated galleries that faithfully mimic the original's dimensions, layout and trappings (down to the burlap wall coverings), the curators have installed founder Albert Barnes' fabled, eclectic collection, exactly as he had meticulously arranged it in the purpose-built, Paul Cret-designed mansion where he had explicitly stipulated everything should always remain exactly as he left it:

Matisse's famous "Red Madras Headdress," 1907, surrounded by a densely packed agglomeration of disparate objects in one of Dr. Barnes quirky "ensembles." (The floors and moldings, not to mention the obtrusive addition at the lower right, are among the contemporary alterations.)

No knockoff can function as an acceptable substitute for the authentic experience of being in the founder's own lovingly tended lair, nestled in a lushly planted arboretum that Dr. Barnes considered an integral part of his creation. Now that they've substantially breached the founder's trust indenture, the foundation's curators might just as well rethink his eccentric, thought-provoking but sometimes vexing installation, which separates closely related works from one another and includes some unfortunate juxtapositions. While Dr. Barnes' arrangement should remain the primary hang, there should be occasional remixes, so that visitors can actually see some of the masterpieces that are placed too high for proper viewing and so that certain works can get to fraternize for a while with their relatives.

The curators could sometimes seek a more suitable companion for van Gogh's virtuous friend, Joseph Roulin, condemned by Dr. Barnes to be eternally ogled by Renoir's come-hither floozy, in what, for me, is one of the place's most perplexing pairings:

While Dr. Barnes was turning over in his grave at the violation of his trust indenture, my stomach was turning over at last week's press preview, as officials repeatedly spoke of honoring the founder's legacy. His collection, they exulted, would now be accessible to "the plain people." That phrase (Dr. Barnes' own words) characterized the collector's envisioned audience for his trove. He famously had no patience for pretentiousness, privilege or elitism. He also famously despised Philadelphia, now home to his collection.

But how many "plain people" of limited means will cheerfully shell out the $18 adult admission fee -- $2 more than at the much larger and more comprehensive Philadelphia Museum of Art, within walking distance down the Benjamin Franklin Parkway? And how many people of limited means, lacking much exposure to, let alone understanding of art, will be motivated to plunk down the astonishing $40 fee for docent tours? The Barnes officials' repeated claims that they are extending cultural opportunities to the underprivileged smack of good intentions at best, hypocrisy at worst.

Even the much-publicized free public admission for the first 10 days of the Philly Barnes (to May 28) is not quite as welcoming as it sounds. Some 7,000 of the 17,000 timed tickets (now all gone) were reserved for those who bought memberships.

That said, children, students and seniors do always get price breaks. There are also four afternoon hours on the first Sunday of each month that are purportedly free to the public, but members apparently are given first crack at those slots. All the free tickets are already taken for June. The Barnes' ticketing website is currently taking reservations only from members for the "free" Sunday hours in upcoming months.

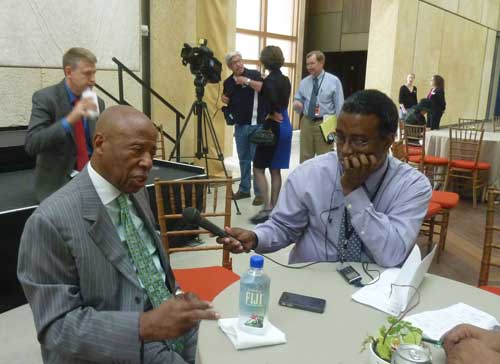

When I asked the Barnes' board chairman, Bernard Watson, about the disconnect between the populist rhetoric and the exclusionary reality of the Barnes' pricing structure, he replied:

You're absolutely right and we have to find ways to do something about that while remaining competitive with other venues. One of the ways is to get [grant] money to support people who cannot afford [the ticket price]. We don't have them [grants for adult admissions] yet. But we'll work at it.

Bernard Watson, board chairman of the Barnes, being interviewed at the press preview

Similarly, Derek Gillman, president and executive director of the Barnes, told me:

We'll make it accessible as soon as we can... What you have to do is make it financially viable and then you add on accessibility wherever you can... I'm British. I love free institutions... In America [unlike in Great Britain, where museums get substantial government subsidies], what it takes is a broad base of support. So you build a broad base of support, you make it financially viable, and then you can make it as free as possible. But you can't if the institution is not viable.

As suggested by Gillman, financial viability -- the issue that convinced a judge to allow the Barnes to move -- is still not assured. Architect Tod Williams, still licking his wounds from the finance-driven closure (and possible demolition) of his firm's American Folk Art Museum facility in New York, told me: "I still worry about this place. There won't be that many visitors here. There can't be: They will admit only 125 people an hour, up to a maximum total [at any one time] of 250." This prudent restriction is designed to prevent overcrowding in the galleries. Even so, annual attendance of 250,000 is projected -- four times the visitorship in Merion.

The most pressing imperative is to raise an operating endowment sufficient to support three campuses -- Philadelphia, Merion and Ker-Feal, Dr. Barnes' little-known country estate (closed to the public) in rural Chester County. Gillman told me that the endowment now stands at "approximately $60 million and we want to go to $100 million." But only about $30 million is currently in hand; the rest of the $60 million consists of pledges, Gillman said.

Back in 2007, Gillman told me that the Barnes had already raised $50 million for its endowment. But on page 19 of its 2010 tax return (the most recent that has been posted online), the endowment is listed at a mere $8.24 million. (My query to the foundation about the reason for this disparity has, at this writing, not been answered.) It's possible that the bulk of the pledges were to be fulfilled after the opening of the new facility.

Gillman said that the Barnes wants to fund 20 percent ($2.8 million) of its $14 million operating budget through its endowment (with 60 percent defrayed by earned income and 20 percent by annual giving). At an approximate 5 percent endowment spending rate (customary for museums), the $30 million currently in the endowment would throw off only about $1.5 million -- more than $1 million short of the desired amount for operating expenses.

My biggest unexpected disappointment in visiting the new Barnes concerned its exterior architecture. While the building itself is handsome -- sheathed in blocks of lively Negev gray limestone that are hung from a stainless steel frame with bronze accents -- here are aspects of the design that seem to tell passersby, "Keep out!"

Come with me now and see for yourself:

All photos by Lee Rosenbaum