CIUDAD JUÁREZ, Mexico — María Guadalupe Güereca wanted to hold her son.

Instead, Mexican police held her back from the crime scene. So she watched him from above the canal that carries the Rio Grande between the American city of El Paso, Texas, and the Mexican city of Ciudad Juárez.

Her 15-year-old son, Sergio Hernández, had been playing with a group of boys along the river, when U.S. Border Patrol agent Jesús Mesa Jr. went to apprehend them, apparently viewing them either as drug smugglers or people trying to cross the border illegally. He grabbed one of the boys on the U.S. side of the river canal, as the rest fled. Sensing that someone was throwing rocks, he turned toward Sergio, who had taken cover behind the bridge piling on the Mexican side of the river, and shot him in the face.

The medics who arrived on the scene soon ceded their job to the coroners. But Güereca swears she saw her son move.

“My boy was alive when I got there,” Güereca said. “But they wouldn’t let me down to see him.”

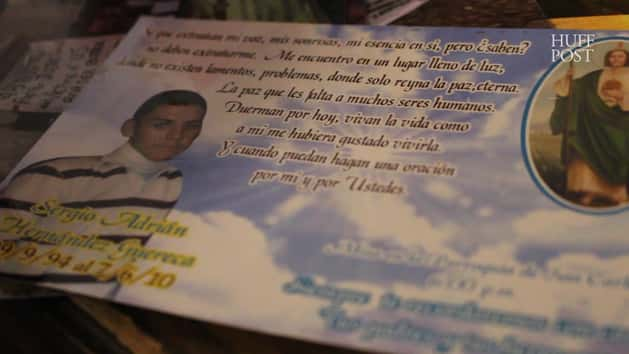

With the help of a Texas law firm, Güereca and her husband, Jesús Hernández, sued the Border Patrol agent in federal court for the July 7, 2010, killing, claiming he violated their son’s constitutional rights. But Mesa’s lawyers convinced a series of courts to reject the claims, relying on longstanding precedent that makes it all but impossible for a noncitizen to hold federal officials responsible for misconduct that occurs on foreign soil ― even when someone’s child dies, and even if the bullets that killed him were fired from the United States.

In 2015, 15 judges on the conservative-leaning U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit concluded in a short, unsigned opinion that because the teen was “a Mexican citizen who had no significant voluntary connection” to the United States and was standing on Mexican soil, the American Constitution doesn’t protect him. But a number of them wrote lengthy concurring opinions ― they were evidently torn on the correct rationale for their decision.

Now it’s the Supreme Court’s turn to hear the dispute. On Tuesday, the justices will confront whether the border is “a unique no man’s land ― a law-free zone in which U.S. agents can kill innocent civilians with impunity,” as lawyers for Sergio’s family put it in their appeal.

Hernández v. Mesa, as the case is known, will mark the first time a Department of Justice lawyer working under President Donald Trump ― who rose to power on charged rhetoric against Mexicans ― will argue for the government before the Supreme Court. Expanding constitutional protections for people like Sergio wouldn’t just allow Hernández and Güereca to sue Mesa in an American court and maybe obtain some monetary relief. A ruling in their favor could have sweeping consequences, opening up Border Patrol agents to civil liability for similar cross-border incidents, which are far from isolated.

The case has drawn a chorus of advocates and legal scholars to Sergio’s side — including the Mexican government, which has weighed in on the case to stand up for its sovereign interests and the teen’s family.

“The United States would expect no less if the situation were reversed and a Mexican government agent, standing in Mexico and shooting across the border, had killed a U.S. national standing on U.S. soil,” Mexican authorities said in a court brief filed ahead of Tuesday’s arguments. The U.S. wants to have it both ways, the Mexican government contends: It refuses to allow its own courts to exercise civil and criminal jurisdiction over the shooting, but it also won’t let Mexico extradite Mesa so he can face the justice system there.

The Hernández family itself feels ambivalent about the support they’ve received from the Mexican government. Local officials promised the traumatized parents therapy, but they never received it. Mexican officials paid for the funeral. But five years later, when Güereca went to place a tombstone at the grave, she was told the site didn’t belong to her. Government officials had failed to pay and only made good after she showed up at the graveyard with a reporter, she said.

In a telling brief, a group of former internal affairs officials with U.S. Customs and Border Protection, which oversees U.S. Border Patrol, advised the Supreme Court that increasing militarization, poor hiring and training, and a culture of corruption within the agency are to blame for the lack of accountability for use-of-force incidents on both sides of the border. By their estimates, since 2010, at least eight people on the Mexican side have been shot and killed by agents. CBP’s own figures for 2010 to 2016 put the overall number of incidents involving firearms in the hundreds, and a separate investigation by The Arizona Republic concluded at least 45 people ― 13 of them American ― died at the hands of CBP officers and Border Patrol agents between 2005 and 2014.

“The Constitution switch turns off while Mesa is standing in the U.S.,” said Bob Hilliard, a longtime trial lawyer who has worked on the case since former President Barack Obama’s first term and will argue it at the high court. He said he agreed to represent Sergio’s parents out of conviction, and that to him the case is about “the most fundamental right of all ― the fundamental right to live.”

Warning: The photo below may be disturbing to some readers.

Because the case has been dismissed at a very early stage, no court has conclusively determined the events leading up to Sergio’s death. But this is how the family’s lawyers and judges so far have characterized them, and how Sergio’s parents remember the day their 15-year-old was killed.

The day Sergio was shot, he and a group of friends were playing a game, running across the border and jumping up to touch the border fence, then scurrying back, according to court filings. Each time they crossed the river, they entered U.S. territory. The temperature reached more than 100 degrees that summer day, leaving the tunnel’s riverbed nearly dry.

Mesa, a Border Patrol agent, bicycled over to stop them. Weapon drawn, he grabbed one of the boys as the rest scattered. Sergio hid behind a pillar supporting one of four international bridges that carry tens of thousands of people between El Paso and Ciudad Juárez daily. Bystanders filmed the scene from afar with their cellphones.

Some of the boys threw rocks, although the family’s attorney says Sergio wasn’t one of them. Mesa turned toward Sergio and fired twice, obliterating his left eye socket and leaving him on his back in a pool of blood, according to the Mexican homicide report. Mesa was standing in U.S. territory, but the bullet punctured Sergio’s brain 36 feet away, in Mexico.

The U.S. Department of Justice ― in conjunction with local federal prosecutors, the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security ― declined to prosecute Mesa. That’s par for the course: criminal prosecutions for cross-border shootings are virtually nonexistent. (The criminal trial of Lonnie Swartz, the only Border Patrol agent to ever be indicted in federal court for the cross-border killing of a Mexican national, is scheduled to go to trial in June; a separate civil case against him is pending in another appeals court that is awaiting the outcome of Hernandez’s case.)

“The U.S. government regrets the loss of life in this matter.”

- Department of Justice announcement declining charges for Border Patrol agent Jesús Mesa

“The U.S. government regrets the loss of life in this matter,” read a DOJ press release in 2012 announcing the federal government wouldn’t charge Mesa with murder or a civil rights crime. The statement went on to say its investigation into Sergio’s death “took into account evidence indicating that the agent’s actions constituted a reasonable use of force or would constitute an act of self defense in response to the threat created by a group of smugglers hurling rocks at the agent and his detainee.”

Mesa’s lawyer, Randolph Ortega, was with him “since under one hour after the trigger was pulled,” Ortega said, and accompanied him to every interview the federal government conducted as it investigated the incident.

Mesa retained Ortega through the legal defense fund of the National Border Patrol Council, the union that represents Border Patrol agents. The union generally feels that the public underestimates the threats agents face daily when patrolling the border and viewed Trump’s election as a mandate to carry out their duties more aggressively. Shawn Moran, a spokesman for the union, declined to comment on the specifics of Mesa’s case, but said the organization is watching the Supreme Court case closely and may say more once a decision is handed down.

Citing his client’s privacy, Ortega offered few details about how Mesa has dealt with the fallout from the civil rights lawsuit against him. The agent remains employed with U.S. Customs and Border Protection. But the case has upended Mesa’s life as well, his lawyer said.

“He’s had to uproot his family from El Paso, Texas, and moved hundreds of miles away, which has caused them significant hardship,” said Ortega, who has more than 20 years of experience representing Border Patrol agents. “He’s had threats on his life and so has his family.”

“This is an area that’s generally utilized for two reasons: narcotics trafficking and human trafficking.”

- Randolph Ortega, the border agent's lawyer, on the location where the shooting occurred

Mesa hasn’t attended any of the court hearings in the case and won’t attend the one at the Supreme Court, Ortega said. Cristobal Galindo, one of the local lawyers for Sergio’s parents, said they won’t attend the hearing, either.

Ortega maintained that Mesa, as DOJ concluded, acted in self-defense when he was trying to arrest an undocumented immigrant at the scene who Ortega said was ultimately prosecuted and convicted. Mesa began to open fire after a group of people began to hurl rocks at him as he was trying to do his job.

“It’s not an area of the border where children routinely play,” Ortega added. “This is an area that’s generally utilized for two reasons: narcotics trafficking and human trafficking.” Hilliard and the rest of the legal team for the Hernández family dispute the rock-throwing incident as a red herring that not even DOJ was willing to pin on Sergio.

“Everyone confirmed, including the Department of Justice” when it met with Sergio’s family, Hilliard said, that the teen did not throw a single rock.

Today, the site of Sergio’s death is covered in graffiti commemorating him. On the piling where he crouched when he was shot, his name is written in blue paint above the dates of his birth and death and a cross. Rocks about half the size of golf balls litter the ground, some of them knocked from the roadbed above.

Sergio’s parents have struggled with hearing their son being called a criminal. Just being in the tunnel that day was enough for neighbors to assume he was doing something wrong and that perhaps he brought the shooting upon himself.

By their account, he got good grades, addressed his mother as “jefa” ― Spanish for “boss” ― and avoided problems with gangs at a time when Ciudad Juárez suffered one of the highest homicide rates in the world. “He was very respectful,” his father told The Huffington Post. “He never talked back, at least not to me. For me, he was the perfect son.”

Sergio himself dreamed of working in law enforcement. One day while grocery shopping with his mother, they ran into a soldier. “I’m going to go ask what it takes to become one,” his mother remembers him saying. But the soldier told him, “What you need is not to have a heart. You’ll have to abandon your wife, your kids, your family. They’ll send you to the mountains or somewhere far away.”

After that encounter, Sergio scaled back his ambitions, hoping instead to become a “ministerial,” one of the Mexican federal police officers charged with fighting corruption and organized crime. “I don’t think he ever would have been a soldier, because he was very attached to me,” Güereca said.

The seven years of litigation has fed rumors in Juárez that somehow the parents profited from their son’s death. A man once threatened to kidnap Güereca if she didn’t pay him. She responded by instead asking him for money, saying she didn’t have enough to buy tortillas.

She sold the house where she had lived alone with Sergio after his older siblings had grown up and married or moved ― partly because she was haunted by the memory of her son’s glee the day she bought it, and partly because she needed the money. She hasn’t worked full time since losing her government job, where she had distributed housing materials and food to needy Juárez residents, three years ago.

Now she lives on the outskirts of Juárez under a bald hill inscribed with the message “The Bible is the truth, read it.” The humble two-room home, with concrete floors and little insulation from the desert’s winter nights, belongs to one of her daughters.

She sleeps in a room with two beds – one for her, and Sergio’s, made up with a red blanket and a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle stuffed animal he’d played with as a child sitting on the pillows. “I don’t move it from there because it reminds me of him,” she said. “I’ll always remember him how he was, because he was very happy. I have a lot of things to remember him by … He’ll always be with me.”

Roque Planas reported from Ciudad Juárez, Mexico; Cristian Farias reported from New York. Video produced by Liz Martinez.