On Sunday, October 6th, 2013, The 51st New York Film Festival presented the New York City premiere of Breaking the Frame, a lyrical film testament of the life and art of Carolee Schneemann, by Polish-Canadian filmmaker, Marielle Nitoslawska. The film is part of the series, Views from The Avant Garde, at The Francesca Beale Theater, in the Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center at Lincoln Center, 144 W. 65th Street, New York, NY. For further information, please consult the New York Film Festival website.

It is questionable whether even Sigmund Freud has received a cinematic treatment as evocative of his impact on the culture around him as Carolee Schneemann has received from Marielle Nitoslawska's film, Breaking the Frame. But then Freud and most other biographical subjects haven't had the good fortune of having their every waking step imprinted as persistently--and as presciently--as Nitoslawska recorded Schneemann for what came to accumulate lovingly into several years. The reward has been more than gratifying for both filmmaker and subject, reaching as it does as deeply into Nitoslawska 's own creative reserve to mirror her impressions of a woman who came as close as any artist in America to being a sibyl-like seer of aesthetic and political possibilities for the last decades of the great modern century.

Whether we credit Nitoslawska's indefatigable burrowing through five decades of Schnemann's personal archives, or her reading of the psyche of a woman who has lived to see herself become an American Treasure, Nitoslawska, a graduate of the Polish National Film School in Lodz, composed a consummate fusion of music, imagery, narrative and time that goes beyond the ordinary crafting of a biographical profile. Imposing cinematic rhythms and restraints that make Schneemann seem at times a mythopoetic cypher--an icon we value as much for her reflections on Nature as for her calling out of the power-intoxicated anthropomorphisms that indict the human steerage of Nature into misogynistic and erotophobic dead ends.

The film also owes considerably to film editor Monique Dartonne (also known for her work on the film Incindies) and sound editors Catherine Van Der Donckt and Benoit Dame, who together with Nitoslawska craft a total artwork evoking an epochal tonality that we immediately associate with the bohemian enclaves of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, if not beyond. Those viewers wanting a linear and hard-focused factuality may be put off by the attention to cinematic mannerisms that function as visual corollaries to the cadences of lyric poems or the notation of songs. But even the most stoic audiences should be impressed by the kaleidoscopic phasing of a life that came to embody, if not reconcile, a number of otherwise conflicting artistic and intellectual movements of her day.

While the filmmakers' lenses and microphones make themselves generously evident, this is entirely in accord with the way that Schneemann herself made film and performance art in her early years--with the artist's own voice generously heard. Following Schneemann's lead, Nitoslawska supplies her own stream of voiceover to Breaking the Frame, a convention that here doubles as her framing of scenes and her appraisal of Schneemann as an artist.

"Your flamboyant acts of transgression. Physical and metaphysical connotations. Orifices of erotic sensate bodies, tunnels linking inside to outside. PORTRAIT PARTIALS. Sacred vitality--invoking, conjuring, living."

Such voiceovers throughout the film ensure that we never steer our attention adrift from the woman and artist. Rather our continual consciousness of the filmic process, in remaining true to the structural dictates of avant-garde filmmakers of the time being recalled, makes us aware of the protean evolution that Schneemann was experiencing as she willed herself to become a medium that is every bit as materially expressive as any painting, video or film. Through Schneemann's body, painting was made performance even as performance became painting. The same interchange can be said to have melded Schneemann's sculptures to her ideas, her feminism to her eroticism, her appreciation of history to the modernity that defined her ideological outlook, her biology to the symbology of her culture. Schneemann was nothing if not consummately aware of the potentiality of things becoming interchangeable, one of the traits that she impressed on the artists around her as well as on every generation that came after her to mediate between the materiality and the ideality of the world.

With artists today clamoring to remake and redefine the frame of a picture with virtual theory and technology, we may have to remind ourselves that the film's title, Breaking the Frame, references the state of the international art movements, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, by which artists were striving to break free of the frame and the format of pictures that dominated the reception and the perception of art. Of course, Schneemann ranked among those who advanced such concerns to the point that making a picture became more strategically self-conscious to the artists of the 1960s than the picture itself. And from there she pushed the process of "making" art to the point where that making becomes reconceptualized as performance in a theatrical sense.

But Nitoslawska prefers not to dwell on histories. "I structured the film thematically," she informed me, "rather than by historical periods as in art history, which would be linear, predictive, and utterly unsuitable for a subject like Schneemann. Each sequence conceptually relates to various dimensions of the body (the body being essential in Schneemann's oeuvre). So we have the historical body that questions how art histories are written; the sexual/gendered body as the source of vital energies; the political body, actively engaged in the zeitgeist; the mothering/mortal body, where life is given and taken; the relational body, that unpacks love, violence, social correlations... And so on. Each section has a concentric form, like a Russian nestled doll. At its heart, it is always collaged with other elements, as with the idea of dislocating time and space, of dodging the concreteness of documentary, of enlarging and embodying the art-life nexus of the film."

In making the film itself a virtual consciousness, Nitoslawska and her team help us experience Schneemann's profound difference as both an artist and a woman of her generation. Whereas many other groundbreaking artists around her looked to experimentation and theory as discrete elements and processes in the formation of their ideas and art, Schneemann seems to merge with phenomena and mind as organic wholes not to be broken down, but rather to be refashioned into new intertwining ways of experiencing them. Whereas Fluxus Art, Conceptual Art, and Performance Art, crystalized into movements inhabited by many artists, Schneemann seemed always to have been a singular movement unto herself, an entity who lived art in a way that Duchamp lived art. In this respect, Nitoslawska's finest accomplishment has been to depict Schneemann's unity with Nature and Humanity as the center from which her art and thought organically grew. And as such we come to appreciate the restraint with which Schneemann keeps her art from becoming systematic or formulaic in the fashion of the Fluxus, Conceptual and Performance Artists with whom she is often historically referenced.

But Breaking the Frame never dwells long on either cultural or media issues. Its meandering, often dreamlike, unwinding impresses a range of conversations with the artist conducted on various planes of perception and cognition at once. We are fortunate that Nitoslawska never makes any one of these conversations seem instructional. We receive them as if we are roaming through Schneemann's large rural house, where each room has its own psychic television tuned to a different station of the universe, however much the "programming" refers back to some aspect of the artist's life as a vessel of the great Continuum. Nitoslawska in fact considers Carolee's house "to play an important 'supporting role' in her meditation on space--a physical, domestic, corporeal, and conceptual evocation of the edges and fractures where art is generated." The formal properties of the film mimic the rooms of Schneemann's house, to take on character traits of space. The dark rooms recall memories hard to extract from unconsciousness.

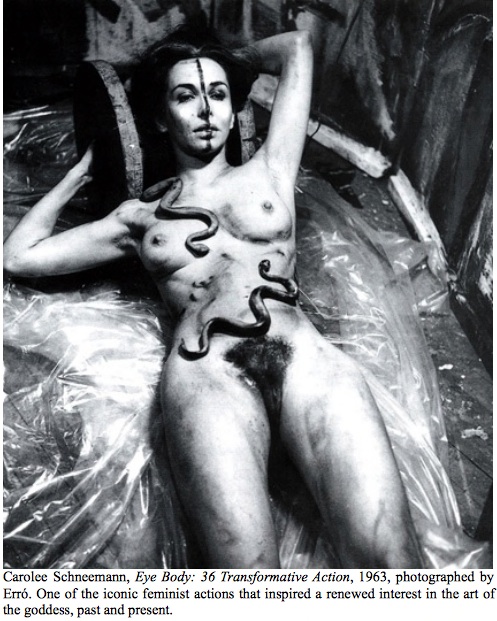

The evocations of the landscape around Schneeman's house are equally affecting. The pools of water and rain psychologically cleanse us of any remorse that comes with reminders of the passage of time. Verdant landscapes seem to justify urges and spontaneity. Not that Nitoslawska burdens her film with gratuitous metaphors. Every choice is conducive to conveying meaning about the moment's environment that Schneemann communes with to the point of merging with Nature as discreetly as a chameleon acclimates to its surrounding. (I here recall the writings of the Surrealist anthropologist, Roger Callois.) If Schneemann came to be associated with the goddess by second-wave feminists, it has less to do with her early embrace of neolithic, bronze- and iron-age iconographies and embodiments of the goddess--of which she was among the first modernists to point to (and would later pave the way for the mythopoetics of such artists as Matthew Barney and Mariko Mori). On the contrary. Nitoslawska helps us to understand that Schneemann assumes not the exalted stature of the goddess, but rather models the process by which living things epitomize processes of nature that in totality dwarf the human condition. The gods, after all, were nothing more than anthropomorphized nature, a process that Schneemann in Breaking the Frame is portrayed reverting to when blurring the animate and inanimate features of the world in her art and thereby subsuming all cultural values in that art's psychological deliquescence.

It helps that much of the film takes on the warm glow of the archival footage that is surviving the now-passing first television generation. The effect of our virtual stay in Schneemann's house is to walk away retaining the living evidence that the artistic avant-garde of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s had more than mere aesthetic and theoretical presence. They were an activist force against governmental and ideological intrusions upon individual liberties however discreetly their forms and processes subverted conventionality. It is the more discreet workings of this generation that compels Breaking the Frame to function as some amalgamation of poem, dream journal, photo album, laboratory log, cultural memento, archeological dig, and liberation manual for an era of artistic experimentation and confrontation. In short, Breaking the Frame is as much a cultural time capsule as a biographical testament.

Nitoslawska makes it evident that our fortune in having Carolee Schneemann with us today has a good deal to do with her being among our last living participants in the strategic break down of taboos that society leveled against the body and its natural functions as late as the 1960s to 1980s. In this respect, Schneemann is much more than one of the significant innovators to have evolved the Pollock and Kline-like actions of modernist action painting into an art of performance that replaces the brush with the body of the artist, while making the artists as much the art as the object and processes they make. The many visual and performance artists in the West who came after Schneemann with their focus and exposure of the body, its functions and products in art, found a more open cultural atmosphere in large part because Schneemann and others of her generation (Kenneth Anger, the Vienna Actionists, Yoko Ono, Yayoi Kusama, Charlotte Moorman, Jack Smith) challenged the remnant superstitions and state ordinances--what amounted to a staggering range of religious, scientific, philosophical, and legislative closures that most of us only read about today. It's hard for us to imagine in our 21st-century, erotically-charged media stream, how the outlawing of public displays of nudity and their referents as pornography legislated an enforcement of moral codes that landed confrontational artists of Europe and North America in jails. At the same time, the challenge Schneemann took on was to impress a newly iconic mediation of art as vehicle for social codes while taking on the political responsibility of remaking those codes and the cultures they build.

If Schneemann's contribution to art history proves more substantial than the performance art of her male contemporaries of the 1950s and 1960s, it is because as one of the earliest exponents of overt feminist dissent in art, she not only famously displaced the millennia-old objectifcation of the female body by male artists with the literal subjectification of her own body as the simultaneously animate mind, instrument, and medium. Add to this her role in tandem with the feminists of her generation and her art is seen as recontextualizing such historic women artists as Artemesia Gentislechi, Hannah Höch, Frida Kahlo, Maya Deren, Lee Miller and Merit Oppenheim, as proto-feminist activists who made the female body (as distinct from the female depiction) a politicized, even polarizing, declaration of independence and autonomy. For good or for bad, the price Schneemann paid for making both art and political history is to have her less activist art, particularly her abstract painting and sculpture, reduced to categorization as remnants or accessories of her performance and body art, rather than as significant art of its own merit.

Breaking the Frame doesn't make art historical pronouncements. It's too lyrical and narrational to be so programmatic. But we are given ample glimpses of Schneemann's movement through art history in the context of the art enclaves that are iconic to this day. Clips from archives are largely circumspect, keeping with Nitoslawska's unifying modus operandi of integrating them into a stream of consciousness, more a seamless fabric than a patchwork composition. In such a stream, glimpses of Schneeman's and other artists' art come into and out of view. One such work is filmmaker Stan Brakhage's film Cat's Cradle (1959), where Carolee is seen chopping onions, "much to her dismay". About this scene, Nitoslawska informed me, "Carolee wished to be portrayed as a painter. She was painting a portrait of Jane Brakhage at the time, and I couldn't believe it when we found five frames of Carolee doing just that, hidden in the Brakhage film. They were there but couldn't be perceived, since five frames is a fifth of a second in projection. So we multiplied the five frames, slowed them right down, and Carolee finally got her due [via Brakhage] fifty years later. (I love the way history is written and rewritten!)"

Nitoslawska clearly relishes the onscreen scenes of Schneemann's eariest performances, such as the iconic Meat Joy, first performed as part of the First Festival of Free Expression at the American Center in Paris, and later at Judson Memorial Church in NYC. "Meat Joy has the character of an erotic rite", Nitoslawska effused about the work's Dionysian lineage. Schneemann's own description of Meat Joy is more grounded in the art media concerns of the period conjoined, in Pop Art fashion, to a virtual shopping list of consumer items and food stuffs that she helped to legitimize as components of art and performance in the early 1960s. "Excessive, indulgent, a celebration of flesh as material: raw fish, chickens, sausages, wet paint, transparent plastic, rope brushes, paper scrap..." But Schneemann departs from and extends the Pop fetish into an intoned litany of human affects that convey Meat Joy to be at its source reverent of Nature: "It's propulsion is toward the ecstatic--shifting and turning between tenderness, wilderness, precision, abandon: qualities which could at any moment be sensual, comic, joyous, repellent."

The influences of artists on Schneemann--and the influence she in turn had on them--are only fleetingly alluded to, but no less saliently. "From the 1950s & 1960s, I mostly focus on James Tenney and Brakhage, as they were the most important in Carolee's formative years. But there are several other references. We see an excerpt of Anthropométrie de l'Époque bleue by Yves Klein (1960) edited in startling contrast with Meat Joy, to show just how radical it was. Carolee was staying with Klein's wife while performing Meat Joy in Paris in 1964, but Yves Klein had already passed away."

From the 1970s we see excerpts from Schneeman's film, Kitch's Last Meal (1973-76). Nitoslawska also includes a long scene with Schneemann and Anthony McCall, with voiceover explaining that the "A" in Schneeman's ABC-We Print Anything-In the Cards (1976) stands for Anthony. "There's also a gorgeous sequence of Carolee spinning in a huge parachute dress that covers and uncovers her naked body", Nitoslawska points out with glee. "This is from Claes Oldenburg's Waves and Washes (1966), filmed by Stan Van Der Beek. Carolee had performed in several of Oldenburg's happenings during his Storefront days. We also see Carolee in an Al Hansen happening from 1965, with several Fluxus friends in the entourage."

The film has also been bequeathed further authenticity of its era by a range of artists who were important to both Schneemann and to the avant-gardes of music, film, video, visual art, theater, dance, and performance art. A good deal of the music saturating several of the film's scenes, and which take on their own biographical association with Schneemann, is composed by her former companion and collaborator, James Tenny--whose handsome young, then middle-aged, countenance animates every cut it inhabits. "Tenney's twenty compositions (spanning five decades) constitute the musical track of the film. He appears on-screen several times as a prescient magician. Our footage of him playing piano at MoMA, in great close-up, is probably the last footage ever shot of him before he dies in 2006." Even the briefest of appearances by the Judson Dancers, Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Robert Morris, and Robert Rauchenberg, are expertly timed to heighten our sense of the radical experimentation afoot in New York's Greenwich Village of the early 1960s.

Schneeman's Water Light/Water Needle (1966), also seen in the film, was performed at St. Mark's Church in the Bowery, and from there moved to the derelict Havemayer Estate in Mah-Wah, New Jersey. Nitoslawska is quick to point out that, "In the film the work is seen to be about gravity and it's defiance. A recurring theme in the film. The bodies horizontally float across space, like drawings in motion. Acts of Perception, the crazy B&W sequence with people crawling on the ground completes the triptych of works that sprang from Carolee's Judson years." As with Meat Joy, Water Light/Water Needle was performed by several Judson dancers and artists. During this period, Carolee also worked on numerous occasions with Lucinda Childs, Philip Corner, Malcolm Goldstein, Deborah Hay, and Elaine Summers. "In the 1960s, people didn't pay that much attention to credits," says Nitoslawska, "so their names don't appear on the works."

I was curious why we never see Charlotte Moorman in the film, an artist and musician whom Schneemann "was very fond of", though we do see Schneemann performing Up To And Including Her Limits (1973-76) for the fist time in The Avant-Garde Festival that had been curated by Moorman. Schneemann answered me anecdotally: "In the Moorman Avant-Garde Festival, each artist was given an empty, rather dirty boxcar in a line at Grand Central Station ... so, we couldn't say it was an exhibit, but something more freeform and chaotic, which was truly uniquely Charlotte's magical system for unpredictable configurations. I participated in many of her Avant-Garde Festivals, and it was I who encouraged Charlotte to be shamelessly nude as she played her cello. When she had an image of descending from a low balcony on a rope harness holding her cello, I thought the image could be Rubinesque. I wrapped her in a sheet which would gradually unfold and fall away as she descended. So she started out as a rather shy southern girl who was afraid to show her body, but once the sheet had fallen away she said 'Wha-Carolee, that surely was a delicious feeling.'"

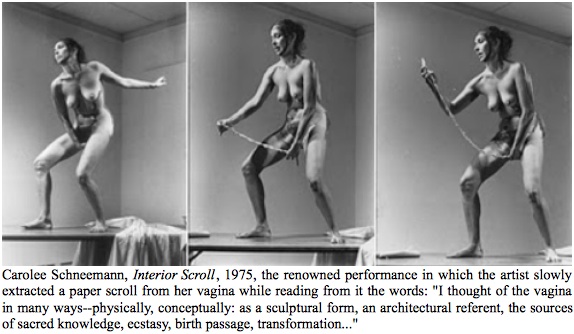

Breaking the Frame also includes documentation of the iconic 1975 performance, Interior Scroll, arguably the most stunningly confrontational act of artistic-feminist dissent waged in the name of women taking back possession of their bodies from the representation and legislation of men. Nitoslawska's handling of the documentation likely required the most delicate diplomacy in the entire film. "The original performance was filmed by Dorothy Beskind," Nitoslawska tells us. "However, this material has never been released by her(!). I initially regretted that we wouldn't have access to these moving images. However, in retrospect, this limitation became a blessing, as is often the case. We 'animated' the stills of Interior Scroll, photographed beautifully by Anthony McCall, and avoided the predictability so often found in filmed documentation of performances. During the making of the film I realized that stills can render the spirit of a performance more accurately than film can. A good still is both a synthesis and an interpretation. Beyond its role as a 'record', it's an 'open work', in Umberto Eco's meaning of the term. Interior Scroll is a powerful work, an early Schneemann manifesto. Dramatic, vital and central to Schneemann's oeuvre, we sought to render its full resonance."

From Interior Scroll, Nitoslawska jumps a span of some thirty years to include the recognition that Schneemann has garnered, along with her many significant artist-feminist peers, at the historical WACK exhibition (2007), where we see many of the notable women artists of Carolee's generation. It's a segue that both underlines the importance of Interior Scroll to feminist art history and acknowledges Schneemann as among the earliest and most visible women activists in the ranks of second-wave feminism.

Although her first imperative was to craft a temporal monument to one of the 20th Century's most pivotal and radical artists, Nitoslawska wishes to remind us that her film is also about film. "In one of my first texts in the film I provide a key to both Schneemann's work and to my formal approach as a filmmaker: Gestalt...collage, montage, a continuous movement of corresponding pieces, breaking in and out of each other, fluidly superimposing, spinning in time." This isn't to say that Nitoslawska competes with her subject. If nothing else, she demonstrates that she is of a mind with Schneemann--that their work is entirely sympatico. "When I ask Carolee what she means by 'inside', 'outside', she replies: How to describe it...you know the proportionate rhythms within the forms, like no two images can just go together and why...because it's inexplicable! These are the last lines of the film." Lines that also summarize the defining principles guiding the entirety of this landmark film.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.