Turkey that is labeled "enhanced" or "flavor enhanced" or "self-basting" or "basted" has been injected with a salt solution at the packing plant. Kosher meat has also been treated with salt at the plant. Do not brine these meats. You risk making them too salty.

But if you have an unadulterated bird -- if you like your meat juicy, tender and flavorful -- there is one simple ingredient that can improve all three: Salt.

Here's how salting and brining can significantly improve your cooking, how they work, how to make wet and dry brines, and how to use them. To learn more about the different types of salt, read my article The Zen of Salt) and click here to read my recipe for The Ultimate Turkey (hint, it is cooked outdoors).

I asked him to explain the difference between osmosis and diffusion, and here is my version of the metaphor he used.

Imagine that the other night you had dinner at a nice restaurant where you ordered a wonderful garlic shrimp entree. You couldn't finish it so they put the leftovers in a plastic doggie bag for you. When you got home you put the bag in the fridge. Before bed, when you had your milk and cookies, the fridge smelled fine. But the next morning, as you grab the milk for your cereal, the fridge had a faint scent of garlic shrimp. That night the scent was stronger, and it got stronger by the day. After a while the smell even got into your milk. That's because the scent molecules could get through the semi-permeable bag and the plastic milk bottle.

This is sort of what is happening with osmosis, vastly simplified. Molecules in a highly concentrated solution bust through a semi-permeable membrane to get into a less concentrated solution until the two reach equilibrium.

Now imagine that for some inexplicable reason you decide to eat the shrimp after a few days. When you open the bag the odors, no longer blocked by the plastic bag, wafts quickly from one end of the room to the other. That is like diffusion, and that is how most of the salt in a brine enters meat (it is really air currents that move odor molecules, but this is a metaphor and not a physics test).

That lean pork loin chop you are brining is not wrapped in a plastic bag. No semi-permeable membrane, no osmosis. But there are plenty of juices on the surface. Salt gets into the meat simply by going through wide open pores, sliced muscle fibers, capillaries and other channels which allow the saline solution to march inward much more quickly and efficiently than by osmosis. Finally, the salt unravels some of the proteins, opening up even more channels.

Now that doesn't mean there is no osmosis at work at all, says Blonder. "In the early stages of brining, salt ions do leapfrog from cell membrane to cell membrane. Inside the cell they encounter water and other large molecules. The larger molecules can't leave through the cell wall so as the salt enters, the internal pressure rises like a balloon. Eventually, the osmotic pressure gets so high the salt ions are either pushed back out as fast as they enter, or the cell ruptures. In other words, the amount of osmosis in small and osmotic pressure sometimes opposes the diffusive motion of ions from the surface into the meat."

Blonder can only speculate why conventional wisdom says that osmotic pressure is the driving force. "Perhaps this is because because the word 'pressure' sounds, well, so forceful compared to random, aimless diffusion." For more technical discussion on the topic, read Blonder's article on his website. For more on osmosis, click the link to visit a college website that explains it in detail with cool animations.

Another revelation: Brines penetrate during low temp cooking

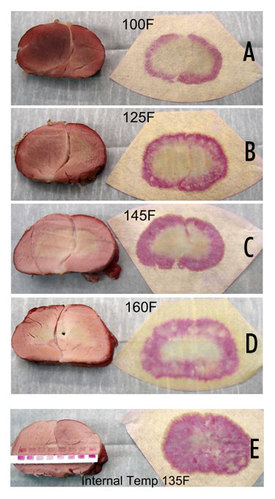

He then took a pork loin that was about 3" tall and rubbed it with a high concentration of a curing salt, a dry brine, that would react with a chemical he put on coffee filters. It sat for an hour in the fridge. He washed it off and cooked it at 230°F. When the internal temp hit 100°F he cut off a slice, applied the filter paper, and you can see the result in picture (A) below, a nice thin pink kiss. As the internal temp rose, you can see that the salt migrated further and further inward, far faster than it does when simply soaking in brine, forming thicker kisses.

In picture E you see a section that had been soaking in a wet brine solution for 24 hours before cooking at 230°F and as you can see the salt has migrated almost to the center during the hour and a half it took for the center to reach 135F. "Diffusion is an exponential process, with the most dramatic movement early on. This is why a 30 minute brine is nearly as effective as a two hour soak." Click here for the technical details on Blonder's experiments, including a discussion of "Fick's Law" and the Gaussian equation he used to plot the diffusion.

Brines do not penetrate very far in short periods. They can penetrate further in long periods, but more penetration takes place during cooking than during the brining process due to the heat exciting the molecules. The most important effect of salting is to improve the water retention of the surface, from which a lot of moisture is lost during cooking, and the amplification of flavor caused by salt.

Dry brining

1) Take the meat out of the fridge about an hour before cooking and pat it thoroughly dry with a paper towel. Sprinkle salt on the meat and let it come to room temp.

2) The salt draws out moisture which dissolves the salt. See how the meat has become shiny with moisture below?

3) The meat reabsorbs the moisture (and much of the juices that have leaked out) bringing the salt in with it. Notice how the color of the fat on the right has changed where the salt has soaked in.

Salt is not evil

Salt is vital to all living things. It is called an "essential nutrient" for humans, which means that our bodies do not make it, so all our salt must be ingested. When dissolved in water, salt conducts electricity and it is essential for aiding the transmission of signals along your nervous system and in your brain. Too little salt in your diet can result in nerve and muscle damage. An average human has about seven tablespoons in their systems. That's why all your bodily fluids are salty: Blood, sweat and tears.

On the flip side, salt is hydrophilic, meaning it attracts the hydrogen (H) in water (H2O); so too much salt in your blood can cause your body to hold too much water, and that excess water can put pressure on your vascular system causing elevated blood pressure. Because most packaged and prepared foods are heavily salted in order to enhance flavor, most of us consume far more than the recommended 1 teaspoon of salt per day.

Salt is so vital to society and health that the words salt, saline and salary have the same root, the Latin word salarium which was the money paid to a Roman soldier to buy salt.

Salt is also a preservative and antimicrobial, which is why so many meats and vegetables were brined, pickled, or packed in salt before refrigeration. Think prosciutto and corned beef. Salt raises the temperature at which water boils and lowers the temp at which it freezes -- and it is also a heckuva stain remover. On that score alone, I say stop picking on salt!

Salt and juiciness

Meat proteins are complex, long and coiled. When sodium and chloride ions get into the muscles, the electrical charges mess with the proteins, especially myosin, so they can hold onto moisture more tenaciously. As a result, less is lost during cooking.

When my favorite food mag, Cook's Illustrated did a test, they discovered that a chicken soaked in plain water and another soaked in a brine both gained about 6 percent by weight. When they cooked both ,as well as an unsoaked bird straight from the package, the chicken straight from the package lost 18 percent of its original weight, the chicken soaked in water lost 12 percent of its presoak weight, and the brined chicken lost only 7 percent of its presoaked weight. Add to that the 6 percent water gain in the brined bird, and you have a hen that is 11 percent more juicy than straight out of the package.

Best of all, according to research conducted by Dr. Greg Blonder for AmazingRibs.com, the brine and the moisture is concentrated near the surface. This counteracts one of the biggest problems of cooking. The meat on the surface is hotter and is almost always overcooked and dry by the time the center is properly cooked. The added moisture near the surface helps the area that needs the most help.

Salt and tenderness

Salt and flavor

On the other hand -- and there is always another hand -- too much salt can make food unpleasant. The trick is to not make the brine too salty and not to leave the meat in too long. Overbrining is just as bad as overcooking. If you overbrine, you are then essentially pickling or curing the meat. That's how corned beef is made, soaking beef brisket in salt and flavored water for a week or more.

Finally, because most brines also include sugar and spices, and some of them penetrate and stick to the surface and flavor the meat, they can also boost flavor by bringing more flavors to the game.

How to bring salt to the game

Wet brining. Somewhere back in time, a primordial hunter felled a dear and it tumbled off a cliff into the ocean. By the time he and his buddies clambered down to the beach and pulled the waterlogged carcass up on shore it had soaked in the seawater, a brine with about 4 percent salt, for more than an hour. They butchered it and schlepped the meat back to the camp where the women waited with a smoldering wood fire. Dinner that night was memorable. You can replicate the process around your campfire by making a salty brine and soaking your meat in it.

Marinating. Another solution (get it?) is to soak the meat in a flavorful marinade. Add salt to your marinade, and you should, and you have a wet brine. Read my article on marinades for more on the subject.

Dry brining. Another method is to dry brine. This is simply salting the meat in advance of cooking. The salt pulls moisture from the meat which dissolves the salt (NaCl) into sodium (Na) and chloride (Cl) ions. They then penetrate the meat and work their way towards the center. The problem is that it is hard to be consistent in how much salt you sprinkle on the meat from one day to the next.

Injecting. Another effective method is to inject meats with water, brine, broth, even butter, margarine or another flavorful fluid. If you do it right, you can add moisture and flavor. If you do it wrong, your meat tastes totally weird or you get pockets of liquid and hunks of dry meat.

Commercial meat packers inject brines into turkey, chicken and pork with rows of tiny needles. Nowadays it is getting hard to find chicken or turkey that has not been pumped up with a brine. Injection is faster than soaking in a brine and also means processors can inflate the weight by 10 percent or so, and charge the same for salt water as they do for muscle. Meat that is labeled "enhanced" or "flavor enhanced" or "self-basting" or "basted" has been injected with a salt solution at the packing plant. Kosher meat has also been treated with salt at the plant. Do not brine these meats. You risk making them too salty.

Watch for a future article devoted to injecting at home.

What to brine

Beware of double salt jeopardy

Also, remember that the drippings from a brined meat will be slightly salty, so if you make a gravy from drippings, be sure to taste before you add salt. Remember, you can always add salt, but it's almost impossible to take it away.

Beware of skin

It is a better strategy to work the salt, along with some herbs and oil, under the skin. The oil helps transmit the herb flavors, and the meat juices dissolve the salt.

Making a brine

The problem in making a brine is that there are different types of salt: Table salt, kosher salt, pickling salt, etc. Some experts recommend you not make a brine from table salt because it has small quantities of other compounds such as iodine mixed in, but I think too much is made of this. I can't tell the difference in taste in the cooked food. So I say good old table salt will do.

But the size and shape of the grains is different for each type, which means the air spaces between each grain is different, which means that the actual amount of salt by weight can vary drastically from one type to another if you measure by volume. For example, one tablespoon of table salt has almost twice as much NaCl as one tablespoon of kosher salt.

Furthermore, if you mix a cup of water with a cup of table salt, you don't get two cups because of the air in the salt. You get more like 1.75 cups. If you use kosher salt you get more like 1.5 cups because there is more air. Read my article on The Zen of Salt for more info about different salts.

But a pound of any of these salts contains the same amount of NaCl. For that reason, salt is best measured by weight, not volume. When you are making a brine, go by weight and you'll never go wrong. At this juncture, permit me to recommend my favorite new toy, the OXO Good Grips Scale with Pull-Out Display. It is also valuable for measuring flour, sugar, chopped onions and other foods which also have the problem of airspaces that make it difficult to measure by volume.

But a pound of any of these salts contains the same amount of NaCl. For that reason, salt is best measured by weight, not volume. When you are making a brine, go by weight and you'll never go wrong. At this juncture, permit me to recommend my favorite new toy, the OXO Good Grips Scale with Pull-Out Display. It is also valuable for measuring flour, sugar, chopped onions and other foods which also have the problem of airspaces that make it difficult to measure by volume.

The Blonder Brine (6.4 percent)

1 cup Morton's table salt = 1.9 cups Morton's Kosher Salt

Substitute one for the other without converting properly and you could badly over-salt your food. It gets weirder because different brands of salt have different volumes. But Blonder knows that a pound of salt, regardless of type, regardless of volume, contains the same amount of sodium chloride. So if you don't own an accurate scale, here's a foolproof method he devised using Archimedes' Principle of displacement:

Basic Blonder Brine (6.4 percent). Add one cup of hot water to a two cup measuring cup. Then pour in salt, any salt, until the water line reaches 1.5 cups. That will be about 1/2 pound of salt by weight. "You'll end up pouring in nearly two cups of kosher salt -- it seems like it will never end -- but once it enters the measuring cup, the water infiltrates the voids between the grains of salt, and compensates for the lower density" he says. "Then dump this slurry into a gallon of cold water and away you go. Easy to remember. Impossible to screw up." This recipe results in a 6.4 percent brine.

Blonder Brine Amped Up (6.4 percent)

Preparation. 10 minutes

Ingredients

Ingredients

1 cup hot water in a 2 cup measuring cup

1/2 pound salt, any type

1/2 cup white sugar

4 tablespoons of garlic powder (not garlic salt)

3 tablespoons ground black pepper

1 gallon cold water

About the salt. Any salt will do, table salt, kosher salt, "sea" salt. The standard round container of Morton's Salt is 1 pound, by the way. Step 1 below shows you how to get it right without a scale regardless of the type of salt you use. Click here for more about The Zen of Salt.

About the sugar. A good ratio for sugar to salt is 1/2 to 1 part of sugar to 1 part of table salt. Molasses dissolves faster in cold water, but it can color the meat. It is good with some meats, bad with others. Ditto for brown sugar which is colored with molasses. If you are diabetic, you can skip the sugar, although truth be told, very little actually gets into the meat.

About other flavorings. Herbs do not dissolve much in a brine so they do not penetrate, so don't waste your money. I have had luck with apple juice replacing some of the water, but I prefer turkey that tastes like turkey, not apple juice.

Do this

1) Add one cup of hot water to a two cup measuring cup. Then pour in salt, any salt, until the water line reaches 1.5 cups. The water will swallow up almost exactly 1/2 pound regardless of whether you use table salt, kosher salt, pickling salt or sea salt. The volume of these salts may differ, but their water displacement will be the same. Pour the slurry into a very clean non-reactive container large enough to hold the meat and 1 gallon of water. Then add the sugar, garlic and black pepper. Stir until most of the sugar is dissolved. The garlic and pepper will not dissolve. Then add the cold water.

2) Submerge the meat in the brine in a non-reactive container and refrigerate. If you can't fit it in the fridge, you can pour it into a beer cooler and toss in a gallon zipper bag filled with ice. Or two. The bags should be tight so that when the ice melts it doesn't dilute the brine. Another option is to fill a quart juice or soda bottle with water and freeze it. Then screw on the cap. Wait until after the bottle has frozen because water expands when it freezes and it can blow off the cap. Wash off the outside of the bottle thoroughly and toss it in the brine. You may need to weigh the meat down to submerge it. If you cannot submerge it, make sure you turn it periodically and extend it's time in the bath. If you brine in a zipper bag (a great technique), periodically grab the bag and squish things around; flip the meat so the brine can get in from all sides.

How long you need to brine depends on (1) the strength of the brine and (2) the thickness of the meat. The total weight of the meat has nothing to do with it. That's because it takes longer for salt to migrate through a 3" pork chop than it does for a 1.5" chop, and it takes more than twice the time.

Before brining, find the thickest part of meat and use the timing guide below. Always err on the underside! An under-brined pork chop will still be delicious, especially if you don't overcook it. When it comes to brining, more is not better. A reader who brined ribs overnight emailed me to say the result tasted like ham from a can.

1/2" thick meat: 1/2 hour

1" thick meat: 1 hour

2" thick meat: 3 hours

3" thick meat: 8 hours

Now these numbers are not precise -- they are guidelines. Start there and adjust to your taste on subsequent cooks. During short brines, the salt remains concentrated very close to the surface of the meat. As you can see from the sidebar, brines penetrate deep when the meat is heated during cooking.

3) Remove the meat, rinse with cold water to wash off excess salt off the surface, and thoroughly pat dry with paper towels. If time permits, let the meat rest in the refrigerator for another hour or more to allow the brine to equalize itself throughout the meat and for the rub to penetrate.

All text and photos are Copyright (c) 2011 By Meathead, and all rights are reserved

For more of Meathead's writing, photos, recipes, and barbecue info please visit his website AmazingRibs.com and subscribe to his email newsletter, Smoke Signals.