Garden and City Context. Albert Večerka/Esto

I've been waiting over five years to write this article. I was privileged to first meet Michael Manfredi and Marion Weiss, co-founders of WEISS/MANFREDI, during my fourth year studying at Cornell University's School of Architecture. Michael was my design studio professor, probably my favorite professor in all my years at Cornell, and Marion was a regular guest critic for pin-ups.

At the time, Michael and Marion had just started designing a visitor center connecting the Brooklyn Botanic Garden and the Brooklyn Museum, and Michael decided to assign this same project to our studio. It was a fabulous experience working alongside an architect who was facing the same design challenges himself, and there's no doubt I developed a strong sense of connection to Michael, the project and its site. So I had been waiting and waiting for construction to be completed and for the doors of the Brooklyn Botanic Garden Visitor Center (BBG) to officially open, and in May 2012, my wait was finally over.

Marion Weiss and Michael Manfredi. Shuli Sadé/ Sadé Studio.

To understand BBG, one must first better understand the philosophy of WEISS/MANFREDI, a firm whose approach to architecture is multilayered, piercing several necessary adjacencies such as art, ecology, landscape architecture, engineering and urban planning. As Michael and Marion often express, to emphasize the distinction amongst these disciplines would in fact relegate the architectural output. One project by Michael and Marion that exemplifies all of these practices is the Olympic Sculpture Park in Seattle, which I included in a previous article, 10 Best Architecture Moments of 2001-2010.

Another friend from my days at Cornell, Mohsen Mostafavi, formerly the Dean of Architecture, Art and Planning at Cornell University and currently the Dean at Harvard Graduate School of Design, shares some profound observations about WEISS/MANFREDI:

A defining characteristic of WEISS/MANFREDI's work from the very start has been the interaction between architecture and landscape. Rather than follow the modernist tradition of envisioning architecture as pure objects in the landscape, they tend to prefer to fuse the two together--except in their case, the landscape is just as artificial as the architecture that conjoins it... Contemporary architecture needs more critical practices like WEISS/MANFREDI.

Michael and Marion graciously hosted me at their new New York City office for an interview and I'd like to share some of this conversation with readers.

Jacob Slevin: As an architecture firm, WEISS/MANFREDI is unique in the integration of landscape and architecture. Please describe BBG and what led to your preoccupation with a reciprocity between landscape and architecture.

Michael Manfredi & Marion Weiss: We started our practice by winning a competition for the Women's Memorial at Arlington Cemetery. It was a national competition on a hallowed site and winning it pushed us into the national limelight immediately. What was exciting about the competition was that the requirements included a memorial, a museum and the redesign of the landscape at the entry to Arlington Cemetery. We proposed a hybrid design-equal parts art, equal parts landscape and equal parts architecture. A 240-foot arc of inscribed glass tablets brought light to the museum below and framed a landscaped entry court to Arlington Cemetery. That design convinced us that we were interested in expanding the role of architecture beyond the limits of the building envelope: Architecture and landscape could be imagined as reciprocal conditions. For us, the most important goal is to design imaginative and original settings free of all the disciplinary boundaries that conspire to differentiate landscape from architecture and vice versa.

Our most recent project, the new visitor center for the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, builds on those original ideas and more fully explores the integration of architecture and landscape.

Garden View from Ginkgo Allee. Albert Večerka/Esto

Garden and Building Pathway. Albert Večerka/Esto

Garden Entry and Retail Pavilion. Albert Večerka/Esto

Green Roof and Upper Garden Terrace. Albert Večerka/Esto

Garden and City Context from Washington Avenue. Albert Večerka/Esto

As you know, the Brooklyn Botanic Garden is an unusual kind of museum, a fragile collection constantly in flux. To provoke curiosity and interest in BBG's world-class collection, we designed a Visitor Center as a legible point of arrival and orientation, an interface between garden and city, culture and cultivation.

Our design intentionally inverts the distinction between building and site. The building is conceived as an inhabitable topography that defines a new "threshold", a gateway between the city and the constructed landscapes of the garden. Like the gardens themselves, the building is experienced cinematically and is never seen in its entirety. The serpentine form of the Visitor Center is generated by the garden's existing pathways. The primary entry to the building from Washington Avenue is visible from the street; a secondary route from the top of the berm slides through the visitor center, frames views of the Japanese Garden, and descends through a stepped ramp to the main level of the Garden.

The building shifts from being overtly architectural at the entry (a broad entry plaza and shaded canopy) to being primarily about the landscape -- it is nested into a planted berm on the garden side where the building with its green roof (including over 40,000 new plants) virtually disappears into the landscape. Our hope is that architecture, landscape and ecology collaborate in a seamless design.

All of this can be put in the context our respective backgrounds. I [Michael] grew up in Rome, Italy and remember playing in the Villa Giulia, one of the great renaissance villas and gardens - to me, the garden was as fascinating as the villa. I [Marion] grew up in Los Altos Hills, California, and remembers the combination of rolling hills and apricot orchards with great fondness.

JS: Clearly the role of water is very relevant with BBG... and at Hunter's Point. Further, you have been talking about flooding and climate change for over two decades. How has it informed your work in light of Hurricane Sandy?

MM&MW: One of our first projects, started over 20 years ago, was the design of a park and community center called Olympia Fields located just south of Chicago. About half way through the design the requirements for storm water retention doubled and the design of the park had to hold much more water in the event of major flooding.

We realized that the requirement to hold flood water in the event of a major storm could actually help create a more interesting design -- so the park is shaped like a giant amphitheater that accommodates playing fields, outdoor music performances and, in the event of a major flood, contains water until it can be safely drained away. The idea that we could be environmentally responsive to climate change and increased flooding and still produce imaginative designs was liberating.

This was also the case in our Seattle Olympic Sculpture Park project, which is one of our most well known projects. It is a complex project that integrates an outdoor sculpture park, a small museum and a redesigned waterfront. We demolished part of a concrete seawall and replaced it with a new ecologically-sensitive beach that accommodates fluctuating water levels - an idea that was virtually inconceivable a decade ago when concrete seawalls were the only engineering solution to flooding. Most importantly, with this new beach design we were able to reintroduce a salmon habitat. It is the first place in downtown Seattle that you can actually touch the water.

At BBG, water is trapped in the building's green roof, which, among other things, is part of a larger water management system. This system also includes a series of "rain gardens" at the entry court and at the event terrace. These rain gardens are in effect "landscaped" cisterns that are planted with water tolerant trees and grasses that hold water in the event of a big storm.

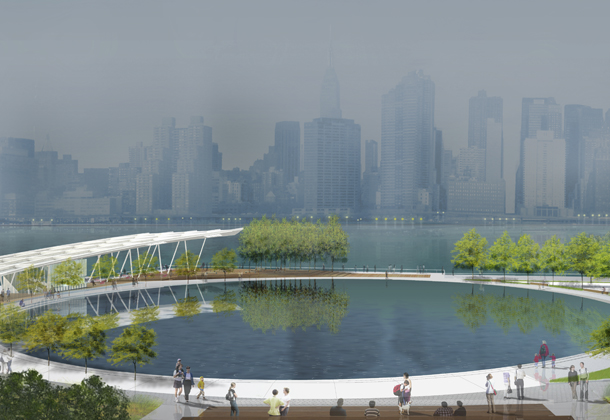

Currently, we are finishing up a very visible project on the East River in New York City called Hunter's Point South. As one of the most ambitious and comprehensive projects undertaken by the City of New York in decades, Hunters Point South is envisioned as an international model of urban ecology.

This post-industrial waterfront site is separated from Manhattan by the slender band of the East River. Two hundred years ago the site was a series of wetlands. However, the site's former industrial uses eliminated all signs of its early ecologically rich history and currently the site is prone to extreme flooding.

We and our collaborators, TBA, proposed a series of linear ecologies that link the northern and southern ends of the site. Along the water, existing concrete bulk-heads are strategically replaced by new wetlands and paths creating an infrastructural, "soft" edge. Think of this edge as a linear "sponge"-- one that can absorb flooding. This is a passive approach to flood mitigation that is in direct contrast to the conventional "put up a big concrete wall" approach. It has the added benefit of creating wetlands and open areas that can be enjoyed.

Water Management, Hunters Point. Image courtesy of WEISS/MANFREDI.

A new multi-use green oval (that can accommodate flooding) defines the most generously open part of the site and offers views directly across the river to Manhattan. This green anchors the park's north precinct and is framed by a continuous path and pleated steel shade canopy on the south side which follows the curve of the oval and offers shelter for a water ferry stop and concession building. The rooftop photovoltaic panels provide enough power to support the pavilion and park lighting.

The walkway that surrounds the green unfurls to a cantilevered overlook at the southern terminus of the site. This overlook, a 30-foot high cantilevered platform with views of the Manhattan skyline and the East River, is at once urbane and otherworldly, bringing the city to a cantilever suspended over new wetland water's edge. This park is characteristic of our passion for an integrated design that weaves infrastructure, ecology, landscape and architecture -- it brings the city to the park and the park to the water.

It's worth noting that we both teach, and many of these professional projects have been augmented by academic research at the University of Pennsylvania, Cornell and Harvard where we have framed a series of research studios over the past decade to identify a more resilient and ecologically vibrant waterfront infrastructure. Through these studio projects, we are able to test different scenarios and bring that research into the design of specific projects like Hunters Point South.

JS: You just won a competition to help redesign part of the National Mall in Washington D.C.. You have been involved in many public projects. What is the role of architecture as it relates to an evolving public realm?

MM&MW: We believe that architecture should & does have a strong social dimension -- it has value and can have a transformative effect regardless of scale or place --whether it is on a street or on a waterfront. We like the saying: "Architecture transforms reality."

We came out of a period in the 1980's where it seemed that too many architects were only interested in pursuing private fantasies: self-indulgent signature houses or signature interiors -- at the expense meaningful public engagement. Instead, we were very interested in projects that straddled the disciplines of architecture, civil engineering and landscape architecture -- projects that, in effect, are part of the public realm and that, regardless of their size, could have a big impact.

Our National Mall project, in collaboration with Olin, is adjacent to the Washington Monument. This area called The Sylvan Theater is one of the major entry points to the Mall and has been the site of open-air theatrical and musical performances. Currently the theater, a public setting, turns its back on the Washington Monument.

Sylvan Theater, Aerial. WEISS/MANFREDI & OLIN

Pavilion Approach from East. WEISS/MANFREDI & OLIN

A New Performance Horizon. WEISS/MANFREDI & OLIN

Our vision for the Sylvan Theater at the Washington Monument Grounds elevates the performing arts, literally and figuratively, with a new amphitheater land-form shaded by a canopy of trees that affirms this site as our nation's center stage. We turn the audience's sights to both the obelisk and the arts and restore lost connections between the Mall and Tidal Basin. The new grove and terraced lawn defines an amphitheater, where a wide range of performances and events can be seen against the stunning backdrop of the Washington Monument. An integral part of the grove is the Sylvan Pavilion, visible from the Mall, the Metro, and 15th Street. The Pavilion, which gently nests itself into the berm, provides an all-weather café, bookstore, and multi-use destination for residents and visitors to the Mall.

So here, a relatively strong and geographically-focused public project can have a big effect: it reinvigorates the Monument Grounds with new landscapes of performance, clarifies the visual connections between the White House, the Washington Monument, and the Jefferson Memorial, provides new physical connections between the cultural landscape of the Mall and the Tidal Basin, and most importantly, creates a transformed public setting for our nation's most visible center stage.

-

Jacob Slevin is the CEO of DesignerPages.com and the Publisher of 3rings & Otto.

Correction: An earlier edition of this article misspelled designer name WEISS/MANFREDI. We regret the error.