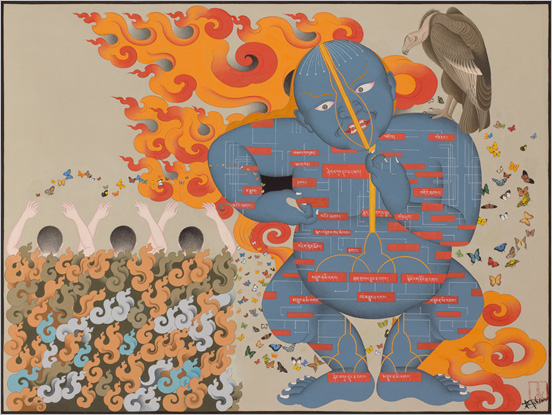

"Chaos Theory: Butterfly Effect" by Tsherin Sherpa (Image courtesy of the Rubin Museum)

Currently on display at the Rubin Museum of Art, Tradition Transformed: Tibetan Artists Respond marks the first major exhibition of contemporary Tibetan art in a New York City museum. The show, which features nine Tibetan artists exploring socio-political, spiritual and cultural issues, brings to the fore a transformative artistic approach of integrating centuries-old traditions and techniques of constructing imagery of Tibetan Buddhist art, with living anthropologies, influences and media.

While several of the artists were born in Tibet, others come from the Diaspora community of Nepal, and other parts of India. A few of the artists, like Dedron -- the only female artist in the show -- continue to work in their Himalayan homelands, though most have emigrated to Europe and the U.S.

Tsherin Sherpa is one of the expatriate artists, currently living in Oakland, California. He comes from an artistic background of thangka -- a specialized type of scroll painting created as illustrated texts for Buddhist teachings -- having made adaptations in his art to express in his work the inner conflict of transitioning from painting exclusively from the perspective of devotee to Buddhism, never signing any of his scrolls, to what it now means for him to express personal tastes and sensibilities in his signed art, which sometimes employs cigarette butts and other garbage, as well as oils, acrylics, wood and canvas.

Bringing these artists together are two curators, one of which is Rachel Weingeist. In a recent conversation, Weingeist spoke about how the artists are sharing their personal artistic freedom; to inform of their responses to the old and the new... East and West.

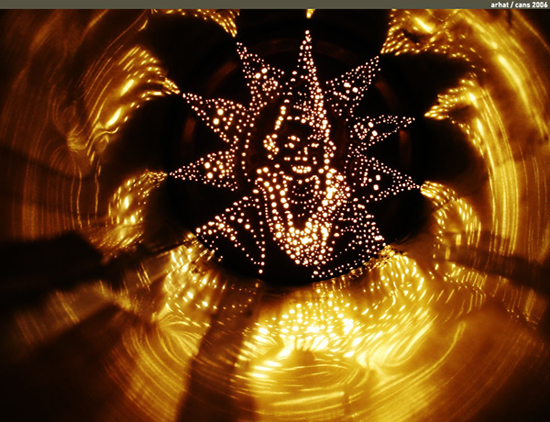

"Arhat" by Kesang Lamdark (Image courtesy of the Rubin Museum)

Max Eternity (ME): So Rachel, how did you become interested in working with the Rubin Museum?

Rachel Weingeist (RW): I've been collecting with the founders, Donald and Shelly Rubin, for over 4 years now, helping to build the contemporary in the their collection -- modern and contemporary Indian -- Southeast Asia. That had not been a part of the mission, but it has become now.

ME: What's the significance of this current exhibition, Tradition Transformed?

RW: In the contemporary art realm, Tibetans have not received a lot of attention. Obviously, what's unique is that most of this work has never been seen; most of these artists have never been heard of. In New York City, the Rubin museum is showing a collection of work from emerging Tibetan artists. Where else is that happening in New York?

The history of Tibetan art, for most who know of yoga or of Buddhist philosophy, knows that the audience is potentially massive. But, I didn't want this to be a general survey. I really wanted to focus on an element of tradition, where the artists are right now. In doing so I focused on artists who primarily have very strong thangka painting skills.

ME: Thangka, what's that?

RW: It's scroll painting. Because Tibetans were traditionally nomadic, their paintings were often rolled up. They were not decorative in any sense. Thangkas were for spiritual practice. They were protected. This ties in with the cultural tradition.

"Liberation" by Tenzin Norbu (Image Courtesy of the Rubin Museum)

ME: And traditionally speaking, what would be involved in becoming a thangka painter?

RW: Thangka painting requires an incredible level of achievement. The training is years and years and years, using stone ground pigment -- malachite, lapis and gold leaf. In Tradition Transformed, some of these artists are using that training to do something very innovative.

ME: One of the artists, Tsherin Sherpa created a piece in the exhibition entitled "Chaos Theory: Butterfly Effect." It has a vulture on the shoulder, there's fire and butterflies.

RW: Yes, that was only the second contemporary piece the artist ever made. His father had been painting in monasteries, and Tsherin had been painting with his father since the age of 12. It took Sherpa until the age of 40 to break from such a strong tradition.

He described to me how afraid he was to break the tradition of thanka painting. There is a formality that's very precise, centered around a deity.

ME: This is so uniquely different from Western thinking -- art centered around a deity.

RW: In Tibetan tradition, there is no history of self expression through art in the culture... not at all. And that is another very significant theme in the exhibition. Not only are these artists breaking from a very long line of tradition, they are doing it in very different ways.

ME: All of the artists in the show bring something unique to the Rubin exhibition. Yet amongst all the men, there's a rather prolific woman artist named Dedron. What's her story?

RW: Dedron is a young woman, 30-something, who lives and works in Lhasa, Tibet. She has two paintings in Tradition Transformed, both of which are large scale paintings done with traditional stone ground pigments. She often paints landscapes and city scenes using Tibetan motifs, like Buddhas, yaks and nomadic life. Unlike most of the other artists, Dedron is one of the few in the exhibition who is not trained in classical Tibetan art.

ME: I'm particularly intrigued by the piece Dedron created, entitled "We Are The Nearest To The Sun." It seems there's a lot of hidden meaning there?

RW: The painting depicts daily life in Lhasa, the highest capital in the world. In it you see, burning juniper berries, prayer flags, animals, open markets, and people circumambulating the famed Jokhang temple. Curiously, many people are viewing Dedron's work as primitive, folk-like painting; implying that it's innocent and perhaps decorative. But, look closer... there is a red flag on the top of the mountain. The eyes are all huge, there are very few mouths. There is a small protest near the top left.

"We Are The Nearest To The Sun" by Dedron (Image Courtesy of the Rubin Museum)

ME: And what about the piece she created depicting her family tree, entitled "Grandparents - Son."

RW: This piece shows the progression from Dedron's traditional grandparents adorned in gold and turquoise. They were nobility. Then you see her parents, who are obviously dressed in the garb of the [Chairman Mao's] Cultural Revolution. Their hair is messy, clothes are tattered, and eyes are red. Thereafter Dedron and her artist husband, Banor, appear in 21st century clothes -- Nike swoosh, goatee. Above them in the cloud is their new son with a tear in his eye.

What is the future of their homeland?

ME: Rachel, as you bring this work to the public eye, what do you feel is the curator's role -- activist, spokesperson, conduit?

RW: Well, for this exhibition it was all about the artists, giving them an opportunity for an audience that they would never have in New York... at this level, with this amount of light shining on them. My drive is that I was able to work with such talent; such great artists -- so humble, so appreciative.

It has since blossomed, and The New School is now teaching a course on the exhibition this fall, and the exhibition is travelling to The Hood Museum at Dartmouth. We also pulled together a catalog with ArtAsiaPacific.

ME: What has the response been thus far?

RW: We saw a completely different type of energy and enthusiasm in the museum. The opening of the exhibition was one of the most well attended that I think the museum has ever had. It reaches out to a whole new audience for the Rubin. Because we are on the fringe of Chelsea, we do have a potentially captive audience as we expand the program to include more contemporary art. Hopefully that audience will be as riveted as I've seen with this exhibition.

I think there are a lot of politics in the Tibetan Diaspora community, and the artists that I'm connected to are very eager to share... mostly, identity issues. They are eager to express their lack of sense of home, combined with a very strong tradition of culture that follows them wherever they go.

Whatever it takes to continue tradition is a worthwhile effort.