-First of all, because the damn thing has fallen so much (i.e., the deficit as a share of the economy). Here at CBPP, everybody's all "fiscal year this" and "FY that..." But given that we just yesterday got GDP for 2013, I'm all like walking around the halls saying, "hey, anyone want to see calendar year (CY) deficit to GDP ratios? They've fallen even faster than the FY ones!"

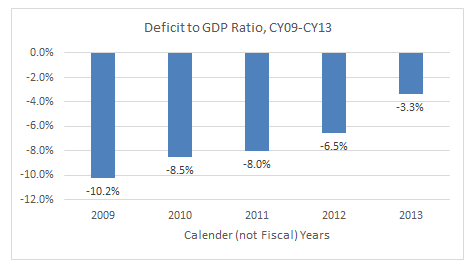

The figure below shows the decline from an historically high 10.2 percent in 2009 to 3.3 percent in 2013 (the fiscal year changes are from 9.8 percent to 4.1 percent). That represents the largest four year decline in well over 50 years.

Source: Treasury, BEA

-Second, it's what you'd expect. Though DC went maniacally hair-on-fire about the deficit, it's supposed to temporarily expand in recessions and come down in recoveries. In fact, it shouldn't come down this fast. That's called austerity, and it doesn't work, if "work" means help the macroeconomy recover from recession. Economists of pretty much all stripes bemoan the estimated 1.5 ppts that fiscal drag sucked out of the 2013 economy, and are looking forward to fewer such headwinds this year.

-Third, that decline in the figure is the partially the result of trillions in spending cuts and tax increases (mostly the former). Last I checked, policy has generated about $3 trillion in cuts, with about 70 percent coming from spending cuts (80 percent if sequestration had stuck, which it still could post-2015). That doesn't mean that our fiscal work is done, as I'll return to in a moment, but it is what's behind the austerity of recent years.

-Fourth, the deficit hawks' prophecies of near-term doom have not materialized. They argued that the deficits would trigger interest rate and inflationary spikes, runs on our currency, boils, and worse. The opposite occurred in every case (not sure about the boils-am sure about the rest).

-Fifth, the politics of deficit reduction haven't helped anyone. I don't know this, and I could be wrong, but if you polled people and asked them: has the deficit improved under Obama, I'll bet most would say, "Absolutely!" (Apparently, polls show that people think Clinton left office with deficits-he left with surpluses.) I think neither the President nor anyone else have gotten any love from the electorate because of the pattern on those bars. And that includes Republicans shut down and default tactics over the debt.

-Sixth, health care costs have slowed considerably and that's reduced -- though far from eliminated -- one of the true sources of out-year fiscal pressures. As my CBPP colleague Paul Van de Water shows, both Medicare and Medicaid are expected to cost the government $1.2 trillion less over the next decade than was earlier forecasted.

-Finally, and this relates to reason #5, a deficit-to-GDP ratio of 3.3 percent creates oxygen for talking about the more immediate challenges that people actually face, including job growth (to which deficit reduction in recent years has been antithetical), opportunity (the topic of both the President's State of the Union and the Republican response), and earnings. If there's anything good that came out of the austerity pattern shown in the figure, it's the fact that both parties are now starting to argue more about how we can achieve broadly shared prosperity as opposed to "grand bargains" (tax increases and cuts to social insurance).

Of course, there are still a) deficit scolds bemoaning their Cassandra-like fate, and b) long-term, serious budget challenges that will require both higher revenues and diminished spending, particularly in health care. I stand by my conviction as a CDSH (cyclical dove, structural hawk). But the key point is timing. Where DC's thankfully-fading-but-formerly-acute case of deficit-attention disorder went wrong is not that the deficit-to-GDP ratio fell so much. It's that it did so at precisely the wrong time.

This post originally appeared at Jared Bernstein's On The Economy blog.