Note: Michael Nichols' Redwood images are on view now at the Annenberg Space for Photography in Century City, CA.

Disclaimer: This is a very personal story about what I went through to make a picture, a reflection of my opinion, not vetted by anyone.

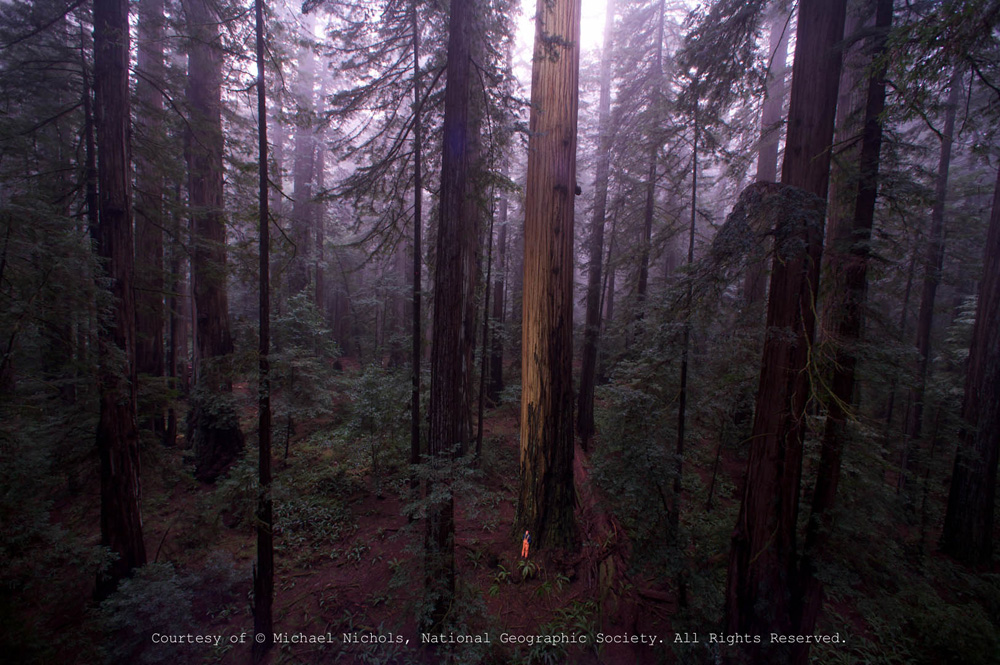

Mike Fay and I have worked together for 20 years. He walked across Africa for 450 days and he's really, really hard headed. Mike's intention with the Redwoods project was to stop the destruction of the conifer forests in the Northwest which includes the redwood range. As a photographer, I had to make this project exciting to the viewer or they would never even pay attention to Fay's desire and agenda. We had to make it sexy first. That meant making one great picture of one of the greatest trees left standing.

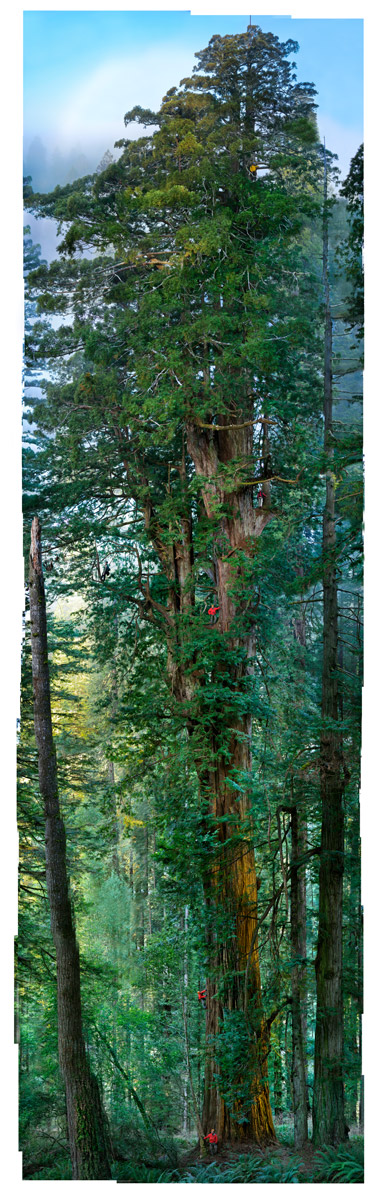

Steve Sillett, the scientist who has found, climbed, named, and studied the old-growth redwoods would also help me. They aren't his trees, but he feels so close to them that sometimes he acts like they are. Obviously, there was pressure from National Geographic Magazine for me to photograph the tallest tree in the forest because that's a great catchphrase. But my research kept leading me back to a certain tree that I knew all the characters who climbed and studied trees felt was The Ultimate Tree, the most complex tree in the ecosystem. And of course, this was the very tree that Sillett told me I couldn't photograph. He's stubborn, much like Mike Fay. Or maybe they're driven.

Meanwhile, James Balog, a famous fine art photographer had made a book called Trees, where he had photographed the most spectacular redwood trees using a mosaic technique which showed the whole tree but as hundreds of individual tiles. He didn't make an attempt to stitch them together seamlessly to create a single, undistorted tree because digital technology was nowhere near as good 7 years ago as it is today. He slid down a rope that was hung between two trees with a camera in hand -a very physical and difficult method to make an undistorted composite. He certainly deserves all the credit in the world as the pioneer in doing this.

I don't like to follow. I need to be original, but I can accept that we're all derivative. I wasn't moved by Balog's pictures because there was no sense of a moment. We were going to put so much effort into this photograph that it had to be more than just a record; it had to give the idea that there was light, that the earth was turning and the sun was shining. I wanted it to have a mood. I couldn't come close to making pictures that convey that sense of awe from the ground, so I knew a big production was ahead of me. So I started using a similar technique to photograph a wonderful tree that Sillett recommended. It was in the Rockefeller grove, a really old, really big, fabulous tree. And I spent three weeks trying to photograph it by climbing an adjacent tree, but failed painting myself into a corner with the view obscured by branches.

So I went crazy. Just before the Christmas holiday, we'd been out there for many months. The story was almost done, but the one thing that was missing was the image that would tie the whole story together, the hook. We knew that it would be a cover story. We knew that there's an National Geographic film coming out at the same time. It was also a combination of: my age, of having been at this profession for 30 years, that I was literally working with the exact same people that worked with Balog, that Sillett was trying to limit which trees I could photograph, and that Mike Fay was mad because we were not concentrating on logging, clear-cutting and "board feet." I didn't realize it yet but I'm starting to get shaky, something is happening to my body that I didn't understand. I'm competitive, totally driven and I felt like I was failing. No matter to how good the other pictures were, if I didn't get this picture, it wasn't going to work.

Then Jim Spickler, my tree guide and the rigger who worked with Sillett, suggested that we use the same precise technique they use to move film cameras through forests: a film dolly. Put the camera out in open space so nothing obscures the view, he said. That way, we can also move the camera with precision on a pulley system so that it can stop at intervals and then paint the tree in with many photographs. He's a gentle soul, he's the one that safely moved me around the trees.

I went home for Christmas realizing that we could do this. But I fell into a deep depression for the first time in my life. Literally, if a bird flew by me, I would start to cry. Is this because of this tree, or because of a long life of this profession? Everyone was worried about me, my children, my life partner Reba, we were all scared, no one had seen me go this way before. The doctors said that the logical thing was to medicate, but I didn't want to do that. I'm not criticizing people who do, but I had a personal feeling that I had gotten myself here, I needed to get myself out. Sissy Spacek, who is a friend, gave me a book called Unstuck which I never finished but I read enough of it to realize that before you medicate you have to try all these other things: diet, sleep, walking. Depression is all about a noisy mind. So I started walking three times a day for 45 minutes at a time. Slowly, after 3 months, the jitteriness and darkness started melting away.

I had to choose another tree. We had to do the tree that Steve Sillett loved the most. The one I was not allowed to photograph. The Park Service had already granted me permission, but I had to assure him that we weren't going to hurt it, that there are already public trails very close by, we won't have to tread on its roots. But moreover, I had to promise that NGM wouldn't reveal the name or location of the tree when we published it. (The question of naming and popularizing trees is a whole other discussion). Steve was shellshocked by uncomfortable celebrity after a bestselling book by Richard Preston called Wild Trees was written about him. He loves these trees and doesn't want them injured by anything that he does. But at the same time we can't not photograph the tree with the potential to empower what we're trying to do for the whole of the redwood range. He finally agreed.

When it came time to go back to the tree, I felt much stronger, the pieces had started to come together. We also had Ken Geiger, an editor and tech wizard at NGM, who was brilliant and patient enough to stitch all the photos together. Jim would take care of making sure the ropes and the tree were safe, Nathan would take care of the camera tech, Marty would engineer the dolly device, Giacomo would climb the tree in the dark every day to tell us when the sun would rise, Steve and Marie would pose in the tree and give us the human reference that we needed. I had a huge amount of help. All I had to do was make sure everyone would be willing to stick with it until we captured the right moment. I can't claim that I made this photograph, it was Sillett's scientific obsession, Mike Fay's drive to save the forest, NGM's resources, Balog pioneering efforts, the team's incredible expertise, it all came together on that one hour on that one day that became this photograph that now the whole world knows.

Ultimately, I'm very happy. What gave me the most satisfaction is when we hung a 60-foot tall print of it in a church in France this past fall at the Visa Pour L'Image Festival. I saw people looking at it, worshiping it. The ultimate goal is not to entertain, but to inspire people to treat the forest in a more considerate way. We honor elephants, whales, owls and tigers but we tend to think of trees as a commodity. A 1,500-year-old tree like this one is perhaps one of the most special things on the planet. And watching the audience consider that makes it all worth it to me.

(This photo was shot on assignment for the National Geographic magazine. To purchase the image, go here.)

-Michael Nichols, Crozet, VA, November 10, 2010

To read more about this story, check out the National Geographic website here!