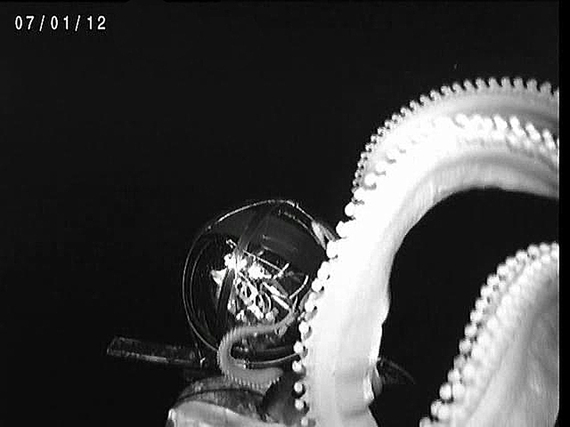

Capturing the first video of a giant squid in the deep-sea was the thrill of a lifetime. How I came to do so, working 600 miles south of Tokyo on a luxury yacht owned by a billionaire hedge fund manager, on an expedition funded by television, using a camera system created on a shoestring budget, was a convoluted tale shaped in large part by our national research priorities.

Exploring the ocean has always been a challenge. The sea is a harsh and forbidding place that swallows ships, sailors and tools for exploration with impunity. Most of what we know about life in the deep comes from net sampling. But it is a truism among marine biologists that nets capture only the slow, the stupid and the greedy (the net feeders). Since most net-captured animals come up dead -- either blown up or cooked alive by the differences in pressure and temperature -- net hauls provide limited insight into the nature of life in the deep. If we want to learn about deep-sea animals, it is far better to go to them than to bring them to us. Scuba allows access to only the thin surface layers. To go deeper we need to protect ourselves from crushing pressures using hard shells called submersibles or unmanned platforms such as remotely operated vehicles. These typically cost between $25,000 and $100,000 per day for a ship and submersible plus crew. This sounds like a lot until you compare it to expenditures for space exploration. For the cost of one space shuttle mission you could make 36,000 submersible dives -- that's almost 50 years of two dives a day. I've made hundreds of dives and on every one of those dives I felt the awesome anticipation that comes from knowing I might see something - some animal or some behavior -- that no one had ever seen before. Space offers no such enticements.

The deep sea is the largest habitat on earth. It is also the least known. We've explored less than 10 percent of our ocean depths and I maintain we've been doing a lot of that wrong. Our tools for exploration use bright lights and noisy thrusters that scare animals away, which helps explain how something as enormous as a giant squid could have eluded our cameras for so long. These tools have always been in short supply and their funding lean. During the course of my career I have watched U.S. support for deep sea science dwindle from lean to anorexic. As a result, deep-sea scientists have had to become increasingly creative in how they support their deep-sea research. A case in point was this Calamari Safari, which was funded by television instead of by one of the federal granting agencies.

Six weeks of funded research at sea is practically unheard of these days but, despite the fact that this appeared to be manna from heaven, I approached the experience with considerable trepidation. Once before, I had been on an expedition funded by television. It was a thrilling trip and I had a wonderful time, but I accomplished little science-wise because, not too surprisingly, the documentary's focus was on getting the perfect shot rather than doing the best possible science. At the time I decided not to repeat the experience, but as I've watched funding opportunities for deep-sea research dry up, (NOAA's National Undersea Research Program was finally zeroed out in 2012) such an opportunity was just too good to pass up.

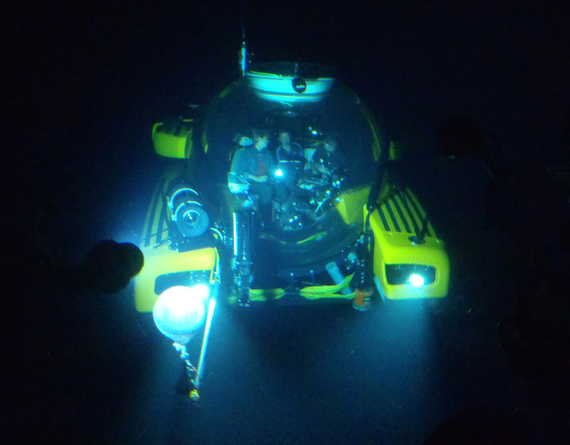

This was a multi-million dollar expedition funded by the Japanese broadcasting Corporation, NHK, with help from the Discovery Channel. The vessel used was the luxury yacht Alucia leased from hedge fund manager Ray Dalio. The submersibles we used were a three-person Triton and a two-person Deep Rover, also owned and leased from Dalio, who, incredibly, owns four deep-diving submersibles. As far as I know that's more than any oceanographic institution in the world. The camera platform I was using was based on a stealth system I developed called the Eye-in-the-Sea that uses red light, (largely invisible to deep-sea inhabitants) and an optical lure that imitates a bioluminescent display, which I believed would attract large predators. When I was first developing the Eye-in-the-Sea, I had a difficult time convincing funding agencies of the need for such a system. As a result it was initially cobbled together from spare equipment and disparate funding sources. Once, when I had occasion to tell a NASA engineer how much that initial system cost ($25K), he laughed and said they wouldn't bother to submit a budget for something that small. As he put it, "That's just the scrapings off the floor at NASA."

Despite its peculiarities, our Calamari Safari was a resounding success. Not only did I have the inestimable thrill of capturing the first video of this creature of legend in its natural habitat, but we had multiple sightings including an incredible 23 minutes filmed from the Triton submersible. How is it possible that a creature that can grow as tall as a four story house could have remained hidden from us for so long? How many unimagined discoveries await us in the depths -- new creatures, new behaviors, new chemicals that could save lives? But as China and others are ramping up their funding for deep-sea exploration, the U.S. continues to cut back, leaving many a deep-sea scientist to resort to crowdsourcing and bake sales to fund their research. We live on an ocean planet and the U.S. is an ocean nation. Our country includes more land underwater than above. It might behoove us to remember those facts as we set our country's spending priorities going forward.

This post was produced by The Explorers Club and The Huffington Post in conjunction with the Club's Annual Dinner on Saturday, March 15, at the Waldorf Astoria in New York City, to honor pioneers in exploration and technology. The authors in this series are all members of The Explorers Club. For more information about the Club, please visit the website, which will feature a live stream of the event the evening of the Dinner. To read all posts in the series, click here.

Watch Dr. Edith Widder's TED Talk here: