We have often stated in this and other venues that the US as a whole, and each state in particular, needs to accelerate the growth of college-educated graduates in order to meet the demand of its industries and remain globally competitive. A rallying cry that echoes what many other advocates have been saying. And now we have a new report from the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) providing us with an update on how we, or at least the state of California, is doing... and the news isn't good.

The analysis estimates that the state will fall about 1.1 million college graduates short by 2030, a significant workforce skills gap. And we should note that the analysis by the PPIC holds if current trends in economic demand persist. But the report itself acknowledges that recovery following the Great Recession of 2008-2009 is still incomplete, and unemployment rates remain higher than pre-2007, which suggests that the employment projections by California's Employment Development Department used in the analysis may be underestimating the actual size of the job demand in 2030.

And there are other sobering data in the analysis:

•Only 38% of all jobs in the state in 2030 will depend on workers with at least a bachelor's degree (and only about 33% of workers will have one then). Which also means that in 2030 fully 62% of all jobs would still require only a high school degree or less. While I found the figure surprisingly low, they are in alignment with the numbers provided by the US Department of Labor statistics (still low in my mind... but that's what happens when you work in academia all your life).

•The share of workers with a bachelor's degree in the state will rise only 1%.... and that assumes that the rate of immigration and the number of college-educated immigrants remains unchanged. However, recent US policy changes have made it harder for immigrants to enter the US, and in fact the overall rate of immigration into the US has dropped by 50% (from a total of 1.8 million migrants per year in 1991to less than 1 million per year in 2013; see Migration Policy Institute data). Thus, something the PPIC analysts rightfully note, it is unlikely that California will be able to close its workforce skills gap solely by attracting enough highly educated immigrants.

•The current wave of baby boomers retirees represents the first time in California's history that such a large and well-educated generation is exiting the labor force. In fact, in the past retirees tended to be less educated and relatively few in number--and were replaced by younger, more-numerous, and more-educated young adults. Not so today.

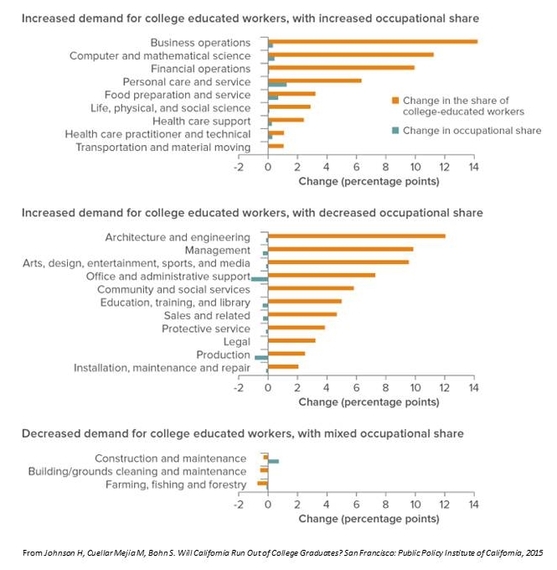

Growth in the demand for college graduates was projected to occur in most broad occupational categories (see Figure), not just in particular occupations. And no significant change in the broad mix of occupations was foreseen, with the current bifurcation in the state's employment (i.e. the demand for those employees with only a high school diploma on one end and those requiring at least a bachelor's degree on the other) continuing.

The analysis did not find any evidence that the increasing demand for college graduates was due to a trend towards having an 'over-educated' workforce, as there was a real wage premium being paid for these jobs. No, employers aren't just demanding more education for nothing.... They are willing to pay for it. However, we should note a recent report from Burning Glass suggests that jobs are experiencing a (paid?) up-credentialing - more employers are now demanding a college degree for jobs that previously did not require one.

There was a smattering of good news in the report. Firstly, the value of a college education was clearly evident in the analysis, with those individuals who had at least a bachelor's degree experiencing a significant wage premium (in 2013, a 72% premium for men and a 68% premium for women relative to same gender graduates with only a high school degree) and a lower unemployment rate (in 2014, 4.5% vs. 11.3% for those with only a high school diploma and 13.4% for those without a high school diploma).

Furthermore, California residents were making positive, albeit modest, strides in college attainment, and in fact, 2010 was the first time in the state's history that more college graduates were born in the state (37%) than in other states (33%) or internationally (30%).

Do these cautionary projections in California apply to other states? While there are significant state to state variations in the types of jobs available and what educational preparation they require (see US DOL statistics), it is likely that the above projections will be replicated in many parts of the union.

The analysis concludes with a few policy suggestions, none of which are new but all worth remembering, including the need to:

1)Increase access.

2)Improve completion and time to degree.

3)Expand transfer degrees.

4)Be smart about aid.

The PPIC analysts also concluded that going forward, California's best approach to closing its workforce skills gap is to concentrate on improving the educational attainment of its residents, as it is unlikely that it will be able to recruit enough college graduates from other states, considering that the demand for college graduates is on the rise in most states, or be able to attract enough highly educated international migrants, as noted above, to close the gap.

And less we make the assumption that educational institutions, particularly public ones, need to make better use of their money towards these goals (not that they shouldn't try), a prior PPIC report noted that institutional expenditures in the Cal State and UC systems--including faculty salaries and benefits--had not increased significantly between 20017 and 2012, with the doubling in per-student net tuition between 2002 and 2012 being primarily driven by reductions of more than 30 percent in state subsidies to these school systems , even as student enrollment increased. To tackle the gap it will take more than just lip service and pressure on institutions.