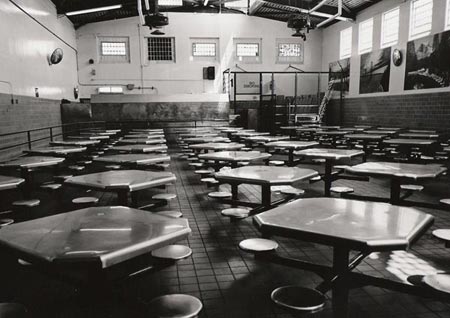

This is a photograph of a room where people have died:

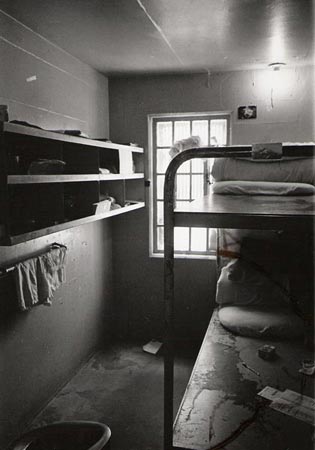

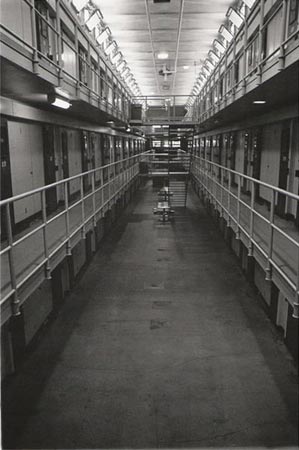

It is in a building next to other buildings filled with hallways where bodies have disappeared only to reappear — perforated, lifeless and jammed under bed bunks exactly like this one:

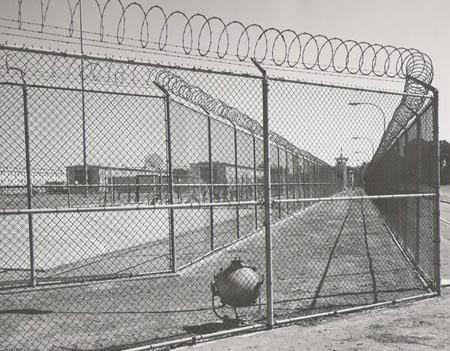

A fence surrounds these buildings. It looks exactly like this:

To stand inside this fence is to stand in the prison where the notorious Mexican Mafia gang first spilled blood in 1957.

To stand inside this fence is to stand where, in the early 1980s, more tear gas was sprayed on inmates annually than in the entire rest of the nation's prison systems combined.

To stand inside this fence is to stand in the Deuel Vocational Institution (DVI) of Tracy, Calif., or as it used to be known, "The Gladiator School".

But this story isn't about DVI.

And it isn't about pepper-sprayed inmates.

It's about the people paid to do the spraying.

Bob Walsh was hired as a correctional officer at DVI between Christmas and New Years of 1980.

At that time, Walsh said, the prison was, "statistically one of the most dangerous places on the planet."

And though it had been opened to house 18 to 24-year-olds deemed capable of rehabilitation, DVI became somewhat of a warehouse for youths too violent for youth facilities.

It was as if bushels of violent teenagers were gathered like dead wood and tossed together in a concrete shed.

Gang members rubbed shoulders like dry sticks. Knives struck like matches.

Tear gas canisters doused like fire extinguishers.

"Places like Folsom and (San) Quentin had gun coverage inside the institution. We didn't," Walsh said. "So when the shit hit the fan, we pumped in tear gas."

"Gas 'em 'till they puke" became the unofficial officers' motto back then -- so much so that, "You can still see it written on license plate frames in the parking lot," Walsh said.

Chemicals clung to concrete walls, drifted down hallways, swelled in eye sockets and lingered on laundry.

Officers were unable to trade in their cars because the upholstery stunk so badly of the throat-swelling stuff.

After work, they'd change clothes in the garage.

But like all problems, this one faded.

In the mid 1980s, California opened new prisons. Gang members were separated. DVI's violence declined.

People weren't dying anymore.

But now there wasn't enough room for all the living.

"Gradually, you end up with almost the whole institution double celled," Walsh said.

"Then you're putting people in the day rooms... And then in the gymnasium... And then in the old laundry room."

"Eventually, you're putting bodies where ever you can put them."

With time, all this affects the way an officer operates.

"But I don't think it's particularly negative," Walsh said. "You get to the point where you spent a lot of your day on condition orange."

Condition orange is a common term in law enforcement. It is a state of mind, an elevated level of awareness.

"You're not just sitting there," Walsh said. "You're actively looking around — listening, planning... where is my avenue of escape?"

"You get two correctional officers on the yard talking to each other," Walsh said, "they don't stand face to face, they stand offset so they can watch each others backs."

"You don't stand at the edge of the tier overhangs. That way people can't drop things like batteries or garbage cans on you."

"Once you are used to it," he said, "you can function in condition orange for hours and hours and hours at a time."

Of course, there are drawbacks.

The old DVI alarm system, for instance, sounded distinctly similar to the alarm on McDonalds' French fry cookers.

"You'd be sitting around eating a burger, the French fry alarm would go off and all of a sudden you jump up."

Referee whistles at athletic events trigger "Pavlovian" responses, Walsh said. "You have to remind yourself, it's ok — I'm not at work."

Condition orange becomes more than an occupational precaution. For those that know it best, it becomes a way of life. And that's the way they like it.

Walsh retired in 2005. No longer does he need to operate on condition orange. But he chooses to.

"I think it's prudent rather than paranoid," he said.

"In school," Walsh said, referring to the class he now takes at San Joaquin Delta College, "I sit at the far wall, almost all the way back. I can see the door and I've still got room to move if I want to."

"Sitting in the corner I don't like because it limits your options too much. Lateral movement is at times a perfectly valid defensive. When you are in a corner you can't do that."

"Little things, I get suspicious about. You get a guy with a long coat during the middle of the summer. Why the hell is a guy wearing that?"

"When I'm on the streets," he said. "There is a 99 percent chance I have a gun on me."

Walsh lives alone on the south side of the city of Stockton.

His wife passed away recently. The remnants of her battle with illness can be seen in the wheelchair pathways he cut into the living room carpet. They never had children.

His house has a security door -- dead bolts, motion sensors and alarm systems. The windows are treated with a film that prevents them from breaking easily. Cameras are positioned around the home's outside.

I know this because I've slept on his couch.

During my visit, we ate steak on TV dinner trays together in his living room.

And as we ate, I thought to myself about how the two of us fell into the modern story of the "Land of the Free".

Here I am, exercising my freedoms by hitchhiking around California with just a notepad and a penknife, choosing to live in a backpack.

And here he is, a man who spent much of his life protecting those freedoms by locking up the people that threaten them, choosing to live behind a deadbolt.

That night, I lay awake on the couch, tossing restlessly and staring at images from the security cameras flickering on the monitor at my feet.

America can be a funny place.

This isn’t to say that DVI didn’t provide vocational training. In fact, its programs were renowned as some of the best in the state. At least, that is, until the money ran out.