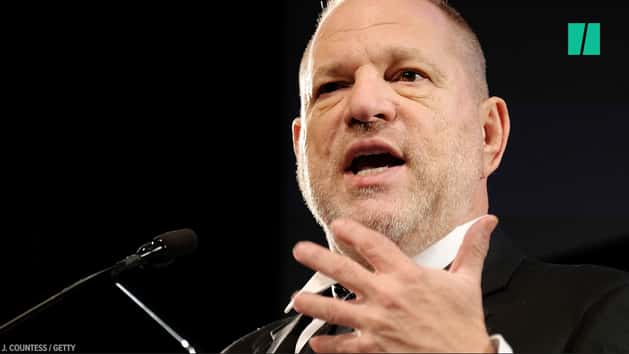

NEW YORK ― There’s a reason women keep quiet about men like Harvey Weinstein, Bill Cosby and Donald Trump for decades before numerous sexual assault accusations suddenly spill out at once. In game theory, it’s called the “first-mover disadvantage”: the idea that a first accuser faces the greatest risk of retaliation or skepticism, especially if no one else follows.

“Information escrows” ― systems that hold onto an encrypted, confidential sexual assault or harassment report until at least one other person has accused the same individual of assault ― could help solve this problem, according to Yale economist Ian Ayres. Just as dating apps like Tinder allow people to privately express interest until it’s returned, technology can keep people’s sexual assault reports private until there’s a “match,” so no one has to make the first move alone.

“Survivors are reluctant to be the first one to file a claim against a particular perpetrator ― the evidence of this is just all around us,” Ayres told HuffPost. “But if you learned that this happened to other people, you’d feel much more confidence that it’s appropriate to bring a claim. And there are good reasons to believe that many offenders are repeat offenders.”

In 2015, Ayres helped to develop a new sexual assault reporting app, Callisto, which is already in use on college campuses and could soon spread elsewhere. Callisto connects people who have reported problems with the same individual and enables them to submit their reports together to campus authorities.

According to Callisto’s data, 15 percent of reports in the system have found a match so far, and students who use the app take less than half the time ― about four months ― to report sexual assault than the average college accuser.

“We’ve had survivors explicitly say, ‘I would not have reported if it weren’t for Callisto,’” Jess Ladd, CEO of Callisto, told HuffPost.

In the wake of the assault allegations against Weinstein, Ladd is now being bombarded with requests to expand the app beyond college campuses.

“I’m getting email message after text after Facebook message from friends and colleagues saying, ‘Look, blank industry really needs Callisto right now’ ― whatever industry they’re in,” Ladd said. “We’re actively considering that and are in the process of figuring out which industry would make the most sense to go into first ― tech? Hollywood?”

“There are good reasons to believe that many offenders are repeat offenders.”

- Yale economist Ian Ayres

Of course, apps like Callisto have drawbacks and limitations. If a man rapes only one woman, for instance, an information escrow will do nothing to help her expose him. Ayres said another concern is that the technology could cannibalize formal reports to the police.

Ultimately, however, sexual assaults are already so massively underreported that Callisto is likely to do much more good than harm, Ayres argues. “The main effect is that it encourages women survivors that would not have placed a formal report,” he said. “They’re motivated now to go forward and use Callisto.

Information escrows would be especially useful to women in workplaces with especially skewed power dynamics, like Congress and the military. A 2016 Human Rights Watch study found that servicewomen are 12 times more likely to be retaliated against after reporting a sex crime than to see their assailant convicted. And Capitol Hill has a notoriously weak internal sexual abuse reporting system, which, combined with political pressure and job uncertainty, keeps staffers quiet. If a group of women could come forward at once against a commander or congressman, they would be more difficult to punish or ignore.

Women have long relied upon underground “whisper networks” in these industries in the absence of any reliable aboveground means of redress. While they can be useful in helping women protect each other from men who are known to be serial predators, they can do little to stop the harassment overall.

Molly Redden, a senior reporter at The Guardian, said she has used whisper networks both to give and receive warnings about certain men in the media. She says an editor once approached her from behind at a work party, put his hands on her shoulders, kissed the back of her head and said, “Don’t worry, it’s just me.” The incident made her “skin crawl,” but reporting him up the chain didn’t seem like an option, since his behavior was already an open secret.

“I’d received warnings about him from other women in the office, and so I’d steeled myself for much worse,” she said. “Plus, this person had zero compunction about being sexist in front of the other editors. I got the message: They knew, they saw, they didn’t care.”

Redden said that while she’s relieved these whisper networks exist, she’s concerned that they may ultimately deter women from taking action.

“I worry that, by whispering about these people, I’m signaling to their next target that she or he ought to keep silent, too,” she said. “That maybe they’ll think, ‘His behavior is not gonna come as news to anyone, so why should I be the one who makes a big stink? Why should I take it so seriously?’”

“I worry that, by whispering about these people, I’m signaling to their next target that she or he ought to keep silent, too.”

- Molly Redden, The Guardian

Apps like Callisto are a useful supplement to underground warning systems because their end goal is the reporting and investigation of a crime. And information escrows could potentially be used in other ways to prevent sexual harassment and legally nebulous romantic behavior in the workplace ― particularly in industries with baked-in power imbalances.

“Right now, most workplaces have a one-bite rule: If you and I are co-employees, you can ask me out once, and if I say no, you can’t ask me out a second time,” Ayres said. “If we could have a rule that employees never got to ask each other out initially, that they could only put expressions of interest into escrow that would only be forwarded if they were matched, there would never be the uncomfortable conversation with the coworker or boss.”

But there are some challenges to expanding the technology beyond college campuses. Callisto’s efficacy, for instance, relies on having a closed network of trust so that any random internet troll can’t come in and file baseless reports. While it’s simple to verify that a user is a student at a particular university, it’s harder to contain and authenticate members across a sprawling industry. “How do you make sure somebody’s a part of Hollywood?” Ladd wonders.

The likely move is to start with groups like the Screen Actors Guild that have long email lists of registered members, in order to authenticate who’s part of the trust network and allowed to make entries.

Sexual Health Innovations would also need help from donors to enter a new market. To use the app, schools currently pay a $5,000-$10,000 setup fee and a $13,000-$40,000 annual fee, depending on school size. Ladd said the nonprofit would need to raise around $5 million to expand to Hollywood or the tech industry.

Callisto has already partnered with the Upright Citizens Brigade, a bicoastal improv and comedy training center, to raise money for the platform, and it’s now seeking other potential sources of funding.

“It’s possible to expand if there’s enough philanthropic support to do so,” Ladd said. “We have the data to show that it’s working.”